Étienne-Jules

Marey (1830 - 1904)

Étienne-Jules Marey, c.1880

During the 1860s Marey

threw himself into the study of flight, first of insects and

then birds. His aim was to understand how a wing interacted

with the air to cause the animal to move.

He also devised some

ingenious apparatus based on his graphical method, such as a

corset which allowed a bird to fly around a circular track

while recording the movements of its thorax and wings.

Marey discovered that the

insect's wing described a double ellipse (a 'figure 8') in

the space of one revolution. Some years later,

chronophotography confirmed that the same was true of the

wing of a bird.

In his lectures at the

Collège de France, where he taught from 1867 onwards, Marey

presented drawings and graphics to illustrate his theories,

and demonstrated machines reproducing the flight of the

insect and the trajectory of its wings. Any aeronauts in the

audience must have been fascinated to see these machines in

operation, no doubt feeling that they were now very close to

their goal.

At this period, French

aviation was in a state of continuous development, with

numerous flying machines being constructed and perfected.

These included dirigible airships, machines with flapping

wings, helicopters, and balloons with wings.

Victor Tatin, Ornithopter, 1875

Yet aviation as we know it

was still in a state of limbo, since advocates of the

heavier-than-air aeroplane were seen as cranks. However

Alphonse Pénaud, a member of the Société de Navigation

Aérienne ("Aerial Navigation Society") presided over by

Hureau de Villeneuve, remained convinced that human flight

would only be possible by means of the aeroplane.

He had identified the

problems which had to be solved in order to build the

machine of his dreams: the resistance of the air, that of

the materials used, and above all the essential need for a

lightweight engine. He had foreseen everything that would

make the flight of aeroplanes possible, but failed in the

application of his theories and finally committed suicide.

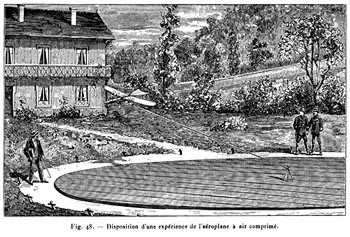

Victor Tatin compressed air

powered Aeroplane of 1879

Marey was no stranger to

the first faltering steps of aviation. He was aware of all

the work, followed Pénaud's research, wrote articles for

Hureau de Villeneuve's journal L'Aéronaute, and even became

vice-president of the Société de Navigation Aérienne in

1874.

Aware that "the most

perfect examples of locomotion which man has achieved are in

general obtained by methods quite different from those of

nature," Marey supported the work of his friend Victor Tatin,

whose aim was to construct, not a balloon or a machine

imitating the flight of an insect or bird, but a true

aeroplane.

He placed the laboratories

and grounds of the Station Physiologique at the aeronaut's

disposal, and in 1879 Tatin achieved his goal. Through

Marey's advice and his own lengthy research and talents as a

craftsman, the device which he designed, one of the very

earliest aeroplanes, completed a flight around the track of

the Station at a speed of eight metres per second.

Victor Tatin aeroplane flying around the track at

Chalais-Meudon

After this first success

Marey continued to support the pioneers of aviation. He

published Le Vol des Oiseaux (The Flight of Birds) in

1890, and presented the work of Clément Ader, a famous

aviation pioneer, at the Académie des Sciences in 1898.

Finally he turned his attention to aerodynamics. His

research in this area included the construction of a smoke

machine which helped him to understand "how the air behaves

as it provides support to the wing".

Marey therefore made a

considerable contribution to one of the great discoveries of

his time. But he died too soon to see true aviation, or to

see that another of his inventions, medical in its nature,

would find use in aircraft (where it is still used today).

This was his "investigative drum", whose principle was to be

used in the design of manometric pressure-measuring

capsules.

|