|

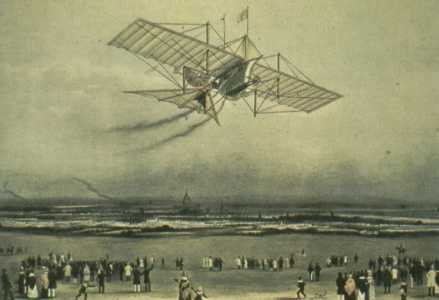

Henson and Stringfellow: The Dream Takes

Shape

Born in 18 12,William Samuel Henson was, like

his father, a successful

industrialist in the lacemaking

business in Somerset, England. In 1840, under the influence

of Cayley’s early writings,

Henson and an engineer who also

worked in the lacemaking industry, John

Stringfellow, designed a

steam-driven airplane they called

an “aerial steam carriage.”

There were many

elements of the design of

the Ariel (as Henson called it) that proved

to be prophetic of later

aircraft, and a simple glance at

the design makes one feel as if one is looking at a cartoon

prototype of the modern airliner.

In fact, Henson and Stringfellow planned to create an

international airline, the Aerial Transit Company,

and proceeded to raise investment

capital. They embarked on

a massive publicity campaign that involved

illustrations of the Ariel in

flight over London and exotic

settings in Egypt, India, and

China.

They hoped that the illustrations would

make people believe the aircraft was an

established fact. These illustrations appeared in

newspapers, magazines, on handkerchiefs, trays, wall

tapestries, and lace-frilled

placemats. The public was caught

unprepared for this barrage, and instead of taking to the

idea, investors who

might have supported it withdrew.

Henson then appealed to George Cayley, who declined

to invest (or even to

endorse the idea until they built a

working model of the Ariel).

Visionary designs

of the nineteenth century:

Henson’s Aerial Steam

Carriage

The pair built a

model in 1847, but the steam engine

Stringfellow had designed was simply not powerful enough.

Finally, Henson abandoned the entire project and emigrated

to the United States, but Stringfellow stayed on and in 1848

tried once more to fly a model with an improved steam

engine. The results were disappointing—nothing more than a

short, uncontrolled hop.

At this point, Stringfellow also

gave up, and the entire episode was forgotten. But the Ariel

did have some positive effects: its design prompted Cayley

to rethink wing configuration and come up with the

multiple-wing design, a feature of nearly all the early

successful aircraft. The plane itself was logically designed

and inspired many later builders. In spite of the scorn

heaped on Henson and Stringfellow’s outrageous publicity,

the many illustrations that found their way all over the

world placed the issue of aviation and the possibility of

comfortable flight to faraway places squarely before the

popular consciousness.

|