The inventive genius unleashed in the early days of flight

was remarkable, but there was little to distinguish the serious

researcher from the

eccentric. The most serious experimenter in this group of

photographs

was August Herring, whose design was later used by

French-born American experimenter Octave Chanute.

The feathered approach proved

a dead end

as did Le Sauteral’s 1923

pedal-powered machine (built in 1923)

and the 1910 design

(snow), which was based on a

discarded (but theoretically feasible) Cayley idea.

Wenham built a model of a five-wing

aircraft that he did not manage to

fly successfully, but his lecture

brought John Stringfellow out of

retirement to redesign Henson’s

Ariel as a tri-wing

airplane. The plane was part of the

world’s first aviation exhibit at London’s Crystal

Palace in

1868, and this time, the more modest presentation

commanded the public’s respect and

attention (even though none

of the Aerial Steam Carriage’s original problems had been

solved).

In

the coming years, a number of experimenters built

and tested powered aircraft inspired by the

Henson-Stringfellow model or by the designs of Cayley

or Penaud. These aircraft made

short hops and glided for

the most part uncontrolled and un-sustained, but these

were necessary steps on the

way to legitimate flight.

The earliest of the short-hoppers included

Jean-Marie Le Bris, a

French sailor inspired by his observations of

albatrosses at sea. His 1857 glider—which was

pulled by a horse down a

track and then, once aloft, allowed to

glide—looked like a large bird.

On his second glide, Le

Bris crashed and broke his leg. In 1868, another version

of his “artificial bird”

(as he called it) was tested

unmanned.

This time the craft simply crashed and was

destroyed. A more serious effort was made by the French

engineer Felix Du Temple and his brother Louis in 1857. Du

Temple flew a model aircraft of his own design—powered by a

spring-driven clockwork mechanism and with unusual

forward-swept wings (instead of wings that stuck straight

out or were swept back). In 1874, a larger version, powered

by an unknown kind of engine, was flown for a short,

uncontrolled hop by a sailor hired by Du Temple. Similarly,

a steam-powered hop in a piloted aircraft occurred in 1884

in Russia, in a plane built by Alexander F.Mozhaiski after a

design derived directly from Stringfellow’s 1868 effort. Two

other experimenters who made short hops were Clement Ader

and Hiram Maxim.

Ader was a distinguished

French inventor who made important contributions to the

development of the telephone. After some experiments with

tethered gliders, in 1882 he built and tested an ungainly

aircraft, the Eole. On October 9, powered by a steam engine

and weighing a light 653 pounds with pilot, the EoIe lumbered forward and rose about eight inches (20cm) off

the ground for a “flight” of about 165 feet (50m). Ader

seemed to think he had been the first to fly, but those

seriously involved in the field would say only that this had

marked the first take-off of a heavier-than-air craft moving

under its own power, but it was not sustained and controlled

flight.

Ader retracted some of his boastful claims, possibly

so that he could obtain further funding for airplane

development from the French government. His second aircraft,

the Avion III, did not even match the performance of the

Eole, and the French government cut off his funding. Ader

was to become a controversial figure in the history of

flight because of the claims he made in 1904 (belied by his

own notebooks) that his 1890 flight was every bit as

deserving of the accolades then being accorded Santos-Dumont

and the Wrights.

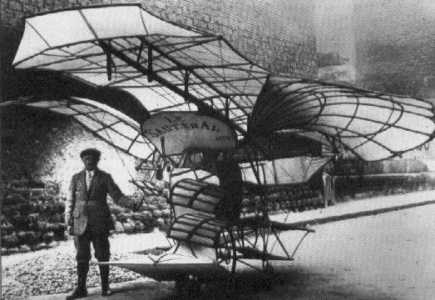

Two machines that might have flown were

Clement Ader’s Avion (LEn’),

grounded when funding was quickly withdrawn after a failed

test in 1897,

Hiram Maxim was born in

Maine in 1840 and became an accomplished draftsman and

machinist. In the late 1870s, he invented the machine

gun and tried to sell it to the U.S. government. The War

Department found his invention impractical and turned him

down, but he found a sympathetic ear at the British War

Office, so he settled in England in 1881. With British

support, he developed a machine gun that could shoot six

hundred rounds per minute, making it a formidable weapon. He

became wealthy from the invention, which allowed him to turn

his attention to a childhood passion—aeronautics.

Maxim was adept at

building lightweight steam engines, including one that

produced 180 horsepower. He constructed a test track that

would allow an aircraft to take off but would then keep it

close to the track. The aircraft he built was huge—two

hundred feet (61m) long with a wingspan of 107 feet (32.5m)

and a wing surface of four hundred square feet (157 sq

m)—and weighed eight thousand pounds (3,632kg); it was

driven by propellers that measured eighteen feet (5.5m) in

diameter. Observers from the British Aeronautical Society

were certain that the craft was capable of flight and had

indeed flown off the track.

More than one observer

urged Maxim to unleash his machine, but Maxim, with an

ebullience some of the British found charming and others

found annoying, insisted that he had paid no attention to

stability and that all he had wanted to demonstrate was that

powered lift was possible with existing engines.

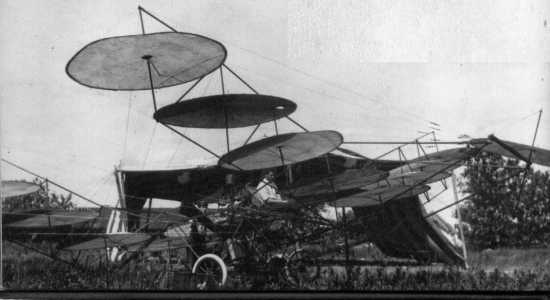

Hiram Maxim’s Giant, which strained against

the rail restraint that kept it from flying.

In this artist’s version, the machine is breaking

through the rail, but is it aloft?