|

Balloons

and Airships of the Nineteenth

Century

Following the flight of the Montgolfier in 1783, ballooning

advanced throughout the 1800s,

becoming popular worldwide by mid-century.

Jean-Pierre Blanchard,

unsuccessful in his ornithopter

attempts, became famous for his

balloon flights all over Europe

and in America. He and John

Jeffries, a Boston physician,

crossed the English Channel on January 7, 1785, and

Blanchard conducted an

exhibition ascent in Philadelphia

in 1793, with George Washington in

attendance.

He trained

the first American balloonist, John Wise, who

in turn trained many others

and engendered enthusiasm for

ballooning in the United States. Blanchard also conducted

spectacular parachute experiments from his

balloons; he died in a fall in 1809.

One of John Wise’s

students, Thaddeus Lowe, provided four balloons for the

Union Army during the Civil War,

and at critical points there was direct telegraph

communication between the balloons and

the White House. A

balloonist alerted the Union of Lee’s breaking

camp in Rappahannock and

setting out for Gettysburg. The

Confederacy realized the usefulness of balloon

reconnaissance and

attempted to put together a program,

but did not succeed in time to be

effective.

The English Channel crossing by Jean-Pierre Blanchard and John Jeffries

marked the beginning of

the Channel’s place in aviation history and inspired the

development of balloon-propeller systems.

Back in France,

Felix Tournachon (also known as

Nadar) developed the art of aerial photography from a

balloon, at one point placing an entire photographic

laboratory on board his huge balloon, Le

Géant, in 1863. Nadar is

also remembered for heroically ballooning mail

and passengers out of Paris

during the siege of 1870. The

nineteenth century ended with the ill-fated

attempt by Salomon August

Andree and two associates, Nils

Strindberg and Knut Fraenkel, to balloon

across the North Pole.

The

trio set out from the island of

Spitzbergen on July 11, 1897; they

soon drifted into the fog and

vanished. In 1930, a Norwegian expedition discovered their

frozen bodies, Andree’s journal,

and even some photographic plates.

The balloon had crashed in the

frozen wastes and all three explorers died trying to

walk back to civilization.

The advantage of placing a

propelling mechanism on a balloon,

making it capable of controlled, directed flight,

was immediately apparent to

everyone, and many designs came

off the drawing boards of nineteenth-

century engineers,

including George Cayley.

The first successful flight

of a steerable airship—or

“dirigible”—occurred on September

24, 1852, in Paris, with Henri Giffard using a

cigar-shaped,

hydrogen-filled balloon driven by a 3-horse-power steam

engine and using a design inspired by

Cayley and others. The

average speed for the flight was only 5

miles (8km) per hour, and the

craft was clearly carried

much of the way by the wind, but the day is often cited as

the date of the first

practical conquest of the skies.

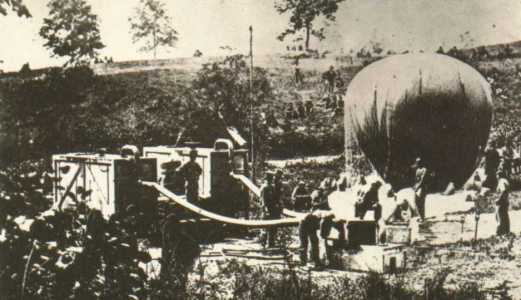

The first observation balloons in the

Civil War were

constructed by Thaddeus

Lowe at Fair Oaks,

Virginia. This 1862

Mathew Brady photograph shows

Lowe, the dark

figure to the right of the balloon,

checking the ropes.

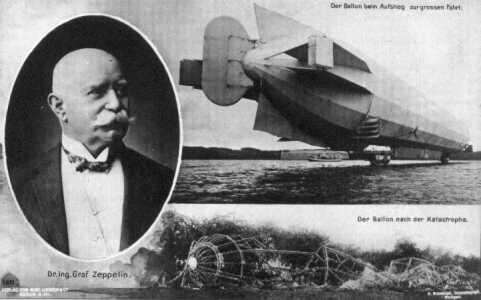

Count von Zeppelin and

the LZ4 were the

pride of

Germany. The vehicle’s

destruction during an

attempt at an

endurance record

actually helped put

the count’s company on

a sound financial footing.

By the late 1880s, many

successful dirigible flights had

taken place and serious thought was

being given to using the

airship as a means of transportation, particularly in

Germany. Two experimental

models, one using a gasoline

engine and the other covered with a thin layer of alu minium

sheeting, crashed during test flights in 1897. But

Ferdinand von Zeppelin, a German army

general who witnessed the

use of balloons in the American Civil War

and followed airship

research for the next thirty years,

created his own company in 1893 and with his chief

engineer, Ludwig Durr, was

preparing to test a 420-foot (12

8m) long airship as a first step in creating a

fleet of ships capable of

transporting sizable numbers of people.

The close of the nineteenth

century also saw the arrival on

the French aviation scene of a diminutive Brazilian,

Alberto Santos-Dumont, who

would become one in the most

colourful figures of the early years of modern

flight.

|