Clément

Ader

(1841-1926)

Self-taught French

engineer and inventor, and a pioneer of flight before

the Wright brothers.

Clément Ader, (b. Feb. 4, 1841, Muret, France--d. March 5,

1926, Toulouse) was an early enthusiast of aviation who

constructed a balloon at his own expense during the

Franco-German War of 1870-71. In 1876 he quit his job in the

Administration of Bridges and Highways to make more money to

support his hobby. His early inventions in

electrical-communications included a microphone and a

public-address device.

He then focused on the

problem of heavier-than-air flying machines and in 1890

built a steam-powered, bat-winged monoplane, which he named

the Eole. On October 9 he flew it a distance of 50 m

(160 feet) on a friend's estate near Paris. The steam engine

was unsuitable for sustained and controlled flight, which

required the gasoline engine; nevertheless, Ader's short hop

was the first demonstration that a manned heavier-than-air

machine could take off from level ground under its own

power.

Between 1894 and 1897

Clément Ader built a larger but still 'batlike' twin screw

machine which he named the Avion.

The Eole

Clément Ader's 'Eole'

in Flight

Clément Ader's 'Eole'

Patent Drawings

Clément Ader's 'Eole',

(Front Elevation)

Clément Ader's 'Eole',

(Plan)

Clément Ader's 'Eole',

Fuselage, (Plan)

Clément Ader's 'Eole',

wing detail, (Plan)

Clément Ader's 'Eole',

wing detail, (Front Elevation)

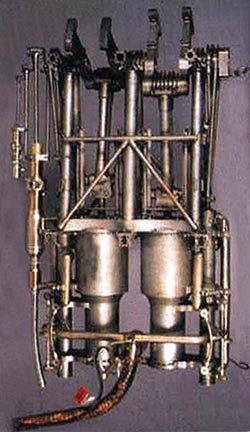

Clément Ader's Eole,

(Side Elevation Alt.)

Clément Ader's Eole,

Motor

Clément Ader's Eole

Clément Ader's Avion III, the "Bat"

Clément Ader's Avion III,

otherwise known as the "Bat", one of the centrepieces at the

Musée des arts et métiers, was restored in the 1980s by the

Musée de l'air et de l'espace at its workshop in Meudon,

near Paris.

The aircraft, which has a wingspan of over 15 metres and is

equipped with two 20-HP steam engines and two propellers,

was built between 1894 and 1897 in Paris, in the rue Jasmin

workshop. The materials used were basically wood and, for a

small number of parts, steel, brass and aluminium. The web

on the wings was made from silk pongee which, in spite of

its tight weave, is permeable to air.

Experiments on the prototype, which required a considerable

amount of work, began in October 1897. Interrupted after an

accident, the work was not continued due to a lack of

financial resources. However, Ader claimed that a 300-metre

flight had taken place, a fact confirmed by two witnesses.

Biruta Kresling was given the opportunity of studying the

airplane close at hand when it was 'dissected' - 'taken to

pieces', enabling her to find out all the details relating

to its manufacture and produce a series of drawings. She was

immediately struck by the great intuition shown by Ader in

transposing the mechanical principles of bat flight,

particularly that of the flying fox.

Clément Ader's Avion

III in 1908

With the impression of experiencing a remarkable adventure,

Biruta Kresling laid bare the aircraft's design, revealing

the astonishingly bionic (before the term was coined)

elements which inspired Clément Ader, engineer and

prodigious inventor, and examining the new ideas he

introduced.

Although the 'Bat' plane remains virtually unknown outside

France, and in spite of the fact that Ader's copy of the

natural model (faithful right down to the terms he used -

'arm', 'forearm', 'fingers', 'elbow', 'wood') seems naive

and clumsy today, all these technical concepts, for which

Ader had no theoretical bases or experimental means at his

disposal other than those he used himself (large flying

models, a glider, the Eole aircraft and, finally, the

life-size plane itself), were extremely advanced for the

time.

The resemblances between the aircraft and the animal are by

no means coincidental. Ader did in fact recommend building

the wings of low-speed planes on the model of a bat's wing,

and those of high-speed planes on the model of a bird's

wing.

Among the many

similarities between 'Avion III' and the flying fox or

birds, we will look at just a few examples.

Doubtless aware that the

pilot would be unable to steer such a complex aircraft

without the assistance of self-stabilizing devices,

depending on the shapes and materials used, Ader invented

mechanisms such as propeller blades inspired by the quills

in birds' wings, made of paper and bamboo - a sort of 'propfan'

and blade 'with automatic variable pitch'. The shaft of the

propeller blades consisted in a central strand made of cork

onto which thin sheets of split bamboo were assembled and

stuck. The unit was mounted in such a way as to flatten out

at high speeds, automatically regulating the angle of

incidence.

The 'thumb' of the flying

fox combines two functions: firstly, the unfurling and

automatic tensing of a membrane similar to the 'leading edge

flap' in an aircraft, followed by the folding back of the

wing, with the thumb now acting as a hook enabling the bat

to grip onto the branch of a tree. The same coupled

mechanism - a safety device for the animal - gave Ader's

flying machine, designed for military aviation, an

essential, dual function: the wing could be tensed and then

folded back, meaning that large wing surface areas could be

reduced. A single mechanism thus facilitated the processes

of putting the aircraft into operation rapidly by unfurling

the wings, bringing it to rest, transporting it from the

airfield to the hangar, followed by fast, easy removal and

dissimulation once it had landed.

X-rays of the 'arm' of

Avion III showed its hollow inner space to be criss-crossed

with thin wooden rods driven into the sides of the tube.

These make the arm rigid, similar to the bony trabeculae -

the thin rods which reinforce the humerus in birds.

As Director of the Musée

de l'air et de l'espace, General Pierre Lissarrague

supervised restoration work on the plane. He began by

carrying out a critical study of the countless technical

notes in Clément Ader's workshop notebooks. In order to

check that Ader's ribless wing did indeed have the hollow

profile announced in the patent, Lissarrague came up with

the idea of testing an original half-wing from the plane,

with its 'arm-bones' and 'fingers', covering it with a new

layer of silk pongee, just like the one on the original wing

which was used as a model, and exposing it to natural wind.

The experiment took place outdoors, on the west coast of the

Cottentin peninsula. The 'automatic ' curve of the thin

'fingers' and the membrane of the aircraft could thus be

observed in simulated flight, as could the profiles along

its wingspan. The placing of reflective strips under the

wing enabled the shape of these profiles to be photographed,

while measuring the way in which they are positioned in

relation to one another.

|