|

The R 36

edited from the

Airship Heritage Trust

|

Statistics:

|

| Length |

675ft |

| Diameter |

78.5ft |

| Speed |

65mph |

| Engines |

2 x 260hp (from the

crashed L-71)

and

3 x 350hp |

| Volume |

2, 101, 000cft |

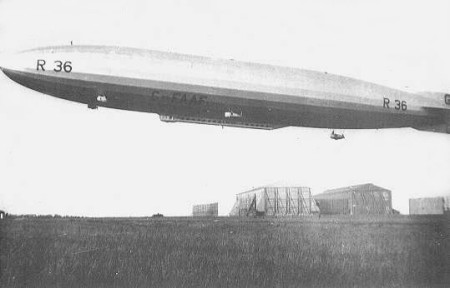

The unique R 36 was the first ship to

carry civil registration for an Airship - G-FAAF, and was renowned

for her passenger accommodation.

With the sudden flurry of airship

production in the late part of the war, it was obvious that when the

war finished that the decisions regarding the use of airships and

their roles were to change. The R36 was one of the last batch of

ships completed in the early 1920's which was force to change with

the situations around it. This did prove however, that the ship could

be certainly classed as multi role.

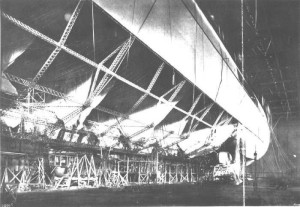

Designed and built by

Beardmore in Scotland, the R 36 truly belonged to the lengthened "R

33" Class of the R 33 and R 34. Her original designs were produced by

the new Airship Design Department and design work commenced in

November of 1917. As with the R33, fate was dealt to the Allies when

the L48 was forced to land at Courbonne-les-Bains in October of 1917,

therefore handing over the Zeppelin design secrets to the Allies. The

R36 and R37 were designed to be a stretched version of the L48,

attaining more lift by adding another bay of some 33ft and giving her

a total length of 672 ft. Her diameter was the same as the standard

'33 class ship of 78ft 9in.

With the role of airships changing from a military scouting role, to

more of a civilian role, it was agreed that the design concept of the

R36 was to be altered during her initial construction phase. Although

construction started during the war, the ship was not finished until

well after and with hostilities ceased, the civil role of the ship

was agreed. The main changes were that the command gondola, which had

been designed as separated from main hull, was mounted flush with the

hull (as with the R31 and R32). A civilian role for the ship was

decided and the R36 was to be able to carry a passenger compliment of

some 50 passengers whom would be able to be granted the latest

comforts, and be able to sleep on board the ship in Pullman type

accommodation. The only contemporary ships at the time which had been

designed to even satisfy the requirements for passenger

accommodation, were the LZ120 "Bodensee" and LZ121 "Nordstern" which

when completed in 1921 could only carry up to 20 passengers. The

project to convert the R36 was at the very least ambitious.

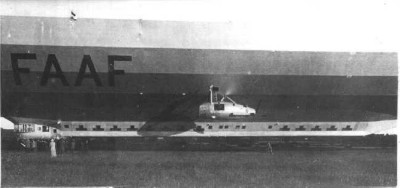

To fulfil the requirement for the

passenger-carrying role, the R36 passenger car was designed to be

attached to the hull behind the control car. The passenger

accommodation straddled the centre of gravity within the ship, and

therefore was able to have people walk about within it, without

effecting the trim of the ship. Entry to the passenger accommodation

was via the nose of the ship, as the bow mooring gear had added to

the ship during construction. The passengers would walk down a

covered triangular gangway along the keel, and then to a staircase

which would lead them down to the passenger accommodation behind the

control car. The car was 131ft long and 7ft 6inches height from floor

to ceiling and 8ft 6inches wide at floor level. The sides of the car

sloped upwards to adjoin the side of the airship hull, and a fairing

at both ends were designed to reduce air resistance.

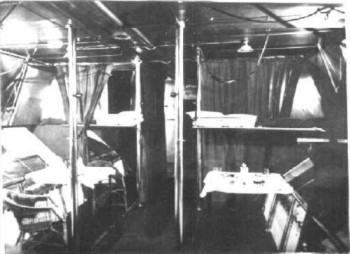

Inside the car were 25 double cabins

arranged along the sides of the car. These cabins were arranged

during the day with two wicker chairs and a folding table. At night

two bunks were released on hinges and let down to provide the

sleeping accommodation, with curtains screening off the cabins at

night. It was noted that the wicker chairs, carpet and general

finishing of the cabin were made of lush blue damask. A galley was

provided for the provision of hot food to the passengers, along with

two sets of lavatories and wash rooms. The "ladies" was places

forward whilst the "gents" was placed next to the Galley amidships. A

storeroom for provisions and luggage space was offered at the aft end

of the car.

The crew consisted of

4 officers and 24 men. This also included A H Savidge who served as

Chief Steward, and later went on to the later civil airships, R100

and R101. The crew accommodation was not within the main passenger

car, but up within the hull as with the normal accommodation on the

'33 class ships.

The R36 carried 5

engines, 3 of which were Sunbeam Maori types and two smaller engines

were recycled from the crashed L71 and added to the front of the

ship. This was the same engine configuration as used on the R101.

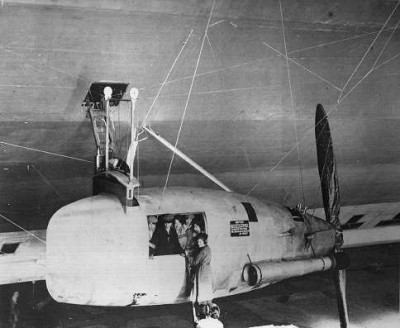

The R 36 was launched

at 3.00pm 1st April 1921 at the Beardmore works at Inchinnan near

Glasgow. The "Captain" of the ship was Flight Lt A. H. Wann, who

later went on to a career with the R38. On her first trial flight,

she flew over Glasgow and Renfrew before returning to the base, some

2 hours later. She was secured back in the shed by 6.45pm.

On the 2nd April 1921

the R36 made her delivery flight to Pulham. The idea being that this

flight was to give the engines a good run and the ship the "settle",

and also a chance for the crew to get the feel of the new ship and

design. The ship left at 7.40pm on the cool evening with a 20-knot

wind blowing. The ship flew down over the Forth Bridge, rounded St

Abbs Head, and then over Berwick, then turned south towards Pulham.

Arriving at 8.00am the next morning, April 4th, the R36 was to remain

in flight over the airfield for crew tests then eased down, and then

finally moored at 12.15 to the mast. The journey time of 15 hours and

35 minutes, covering some 412 miles.

The next day April

5th 1921 the R36 a demonstration flight had been ordered and with

some representatives from the Air Ministry on board, the R36 left

Pulham at 07.25am bound for the outskirts of London. Conditions

became turbulent when the R36 was crossing Chorley Wood and continued

to do so. Continuing down to near Salisbury Plain, the ship rose up

to 6,000ft when she began manoeuvres. In the turbulent air, the R36

began to start a fast turn of 130 degrees with the engine revs

increased. During this turn a wind sheer managed, with the turbulent

air, put severe pressure on the rudder and hence caused the top

rudder and starboard elevator to crumple. This caused the ship to

fall rapidly for about 3,000ft whereby the ship had attained a severe

nose down angle, but this was arrested and the ship was managed under

control and re-trimmed using both crew and water ballast. The R36

climbed back up to 4,500ft and immediate repairs were made to the

damaged control surfaces at the rear of the ship. The demonstration

flight was aborted and the ship limped home on her one remaining

rudder and elevator, and running the engine speeds to give a degree

of directional control. The ship finally made it back to Pulham at

9.15pm, however there was no room to house the ship, as the Pulham

shed contained the R33 and the two German Zeppelin, L64 and L71. The

R33 was quickly taken out of the shed and moored to the mast, and the

R36 moved in to the shed next to the two German ships.

The repairs were

carried out on the ship to repair and strengthen her rudders and

elevators. The R 36 came out on the evening of 8th June for a test

flight. Even though she had been fully loaded for a long flight, it

was decided that the ship would only undertake a local flight for

2hours 15 minutes then returned and secured at 8.15pm.

The next morning, 9th

June at 9.26am the R 36 undertook an extensive flight of 11 hours.

Flying cross-country towards Nottingham, then up towards Manchester

and Liverpool, then return to Pulham. She secured her moorings at

8.30 in the evening after a flight of 11 hours.

The role of the R36

was now coming under scrutiny and it was deemed that the trail

flights were to continue and ideas emerged that the ship should start

to take a role within the Empire communications plan. The idea that

the ship should try a circular route around the Mediterranean and a

non stop flight to the Middle East. These ideas are not so far

fetched, as contemporary sources believed the ship had the range and

the speed to carry this out. Whether in practice she could have

carried out such demonstration flights, we would never know.

The 10th June the R36

was loaded up again for another longer test flight. At 10.00pm in the

evening, the ship slipped the mast, and made her way southwest,

towards London. At 1.00am on the next day, the ship altered course

for Southampton and by 4.00am the ship was over Portsmouth, and out

to the Solent. An impressive speed as today the same journey by rail

takes nearly 5 hours. The ship climbed to 3,500 ft and headed out

over the Solent and set a course towards the Channel Islands. The

passengers could see France some 21 miles away and would have had a

spectacular view over the ocean in wonderful accommodation. Sark was

seen just 2 miles away to the starboard. Passing over St Helier, the

ship turned and headed back to the base, travelling towards Lizard,

in Cornwall. Crossing Cornwall and Devon, the ship took advantage of

a following wind and flew up towards Swindon, Oxford and Aylesbury.

Crossing the Home Counties of Buckingham, Hertfordshire and

Cambridgeshire, then heading towards Suffolk, the ship came in sight

of Pulham at 01.05am. At 4.00am on the 12th June the R36 was secured

to the mast. The R36 completed an epic voyage with considerable ease

over mixed conditions of land and sea, for 29hours and 54 minutes, of

which 446 miles was over land and 288 miles over sea, a total of 734

miles.

The R36's high

profile passenger accommodation allowing her to fulfil a number of

different roles gave cause for a number of requests for the use of

the ship. The Metropolitan Police requested that the ship be used for

aiding in communication traffic congestion around the Ascot Races.

The original "eye in the sky" would be used to signal to the local

Police Force the areas of congestion from above the races.

Only 2 days after the

epic long distance test, the R36 was slipped from her mast at 07.31am

on 14th June with a passenger compliment of both representatives of

the police force and journalists on board for the flight. The ship

flew southwest towards Wembley and Ealing making 60mph, and then

turning towards Windsor Great Park. At 9.45am the R36 was in position

and was watching the roads of Staines and Windsor, reporting to the

police on the ground. A summer lunch of hams and salad with beer,

fruit salad followed by cheese and biscuits was served by Steward A H

Savidge as the ship cruised the countryside surrounding the

racecourse. At 2.00pm the ship overflew the Croydon airfield as the

journalists dropped their reports by parachute to be sent by

motorcycle courier up to Fleet Street in London to make the papers.

As with great British

traditions, afternoon tea was served at 4.00pm and it was noted that

the food and beverages on offer were comparable to the grand scale of

lunch. The ship returned to her traffic reporting duty in the late

afternoon as the traffic built up after the race meeting. The ship

then turned for home, crossing North Hertfordshire and Knebworth

house on route home to Pulham. The R36 was moored at 10.00pm that

day. A round aerial cruise of some 556 miles for 14 and a half-hours,

carrying 60 passengers and crew.

The gruelling trials

continued and the next day the ship was readied on 17th June for

another demonstration flight, this time to Members of Parliament. A

simple summer afternoon flight of 3 hours around the Norfolk and

Suffolk countryside.

On 21st June the ship

slipped her mast at 8.00am for another trial flight. Flying north

from the airship station, the continued up the coast as far as

Scarborough in Yorkshire. There she turned in land and headed for

York and returned via Howden and south to Cramwell, which she reached

at 5.45pm. Turning and heading in an easterly direction, she headed

off home towards Norwich. When coming in to land at Pulham, Commander

Scott took over from Lt Irwin and decided to direct the landing

himself. The mooring rope was dropped at 9.15pm and secured to the

mast. However the ship approached the mast far too quickly and the

rope fouled the bottom of the mast and brought the ship up with such

a jerk that two of the forward emergency ballast bags released their

contents. The bows pitched up sharply and the full length of her

cable halted the ship. The strain caused the bows to collapse at

frame 1. The ship was eased down and put in the hands of the handling

party. By 10.00pm it was decided that the ship be accommodated in a

shed immediately. However the only vacant space was back at Howden as

all the berths at Pulham were full and the mast was incapable of

accommodating a ship.

The wind began to

pick up and it was then decided that urgent action be taken. The

sacrifice of the L64 ensued as, unable to get the ship out of the

shed, it was decided that the L64 be lowered to the shed floor, and

everyone on the base, be set about to dismantle the ship with hacks

and saws. By 2.00am on the 22nd June there were enough space cleared

to accommodate the R36 and the ship eased in to the shed. This is

always a tricky manoeuvre and, as found with the German Zeppelins, an

airship is at it's most vulnerable when being brought in to or out of

the hanger. Whilst being moved in to the shed, a gust of wind caused

the side of the ship to slam against the shed doors and caused damage

to her port side amidships.

The ship was finally

secured at 7.00am on 22nd June. It was noted that Lt Irwin broke down

when he saw how much damaged had been done to the ship. The official

court of inquiry records that the blame fell on equipment failure.

With the R36 in her

shed, and the whole airship scheme under considerable review, it was

decided to leave the ship in the hanger and start repairs until such

time a decision sa to what exactly was to be done with the British

airships. One consideration following the crash of the R38 was

offered by Commander Scott in the setting up of a private company

with the intention of selling the R36 to the Americans as a

replacement for the loss of the R38.

Two years later, with

the revival of the Airship Scheme in 1924 the provision of the

refurbishment of the R33 and R36 was incorporated in to the idea that

the ship be used for testing the routes on the Imperial Airship

Scheme. A grant of £ 13,800 (£483,477 today) was given to have the

ship refurbished and this was undertaken. A replacement outer cover

was added to the ship. The idea being that the R36 would carry out a

non-stop flight to Ismailia in Egypt to gather meteorological and

other data on the trip. Work was finished in August of 1925 and the

ship was due to fly in the October of that year. It was recalculated

that the ship would not have enough disposable lift for the journey,

having a lift of some 16.5 tons for fuel and passengers. It was

therefore decreed that the flight be cancelled. As the airship scheme

continued to gather momentum with the design concepts for the larger

5,000,000 cft ships, the R36, designed some 8 years earlier, would

not fit the current requirements. The R36 remained in the hanger

until June of 1926 when it was decided that the ship be scrapped and

she was dismantled.

It is with interest

to note that there is a set of plans for the R101 in the Public

Record office, showing a concept drawing of the ship with the exact

same engine configuration and a totally external passenger car,

similar in design shape and style to that of the R36. This of course

was later evolved in to the R101 design as well known today.

Even though the R36

was initially built to be a military airship, her conversion in to a

civil role proved that she could carry out the flights and provide

comfort and luxury which was later continued in the larger ships. She

was a groundbreaking airship who in 1921 had a passenger compliment

larger than contemporary airships to even that of the Los Angeles and

Graf Zeppelin. She would only be surpassed by the later ships of the

R100 and R101 in passenger comfort. Her unique lines and layout gave

her a sleek style all her own and not copied or surpassed by any

other airship ever built. |