|

the

Shenandoah

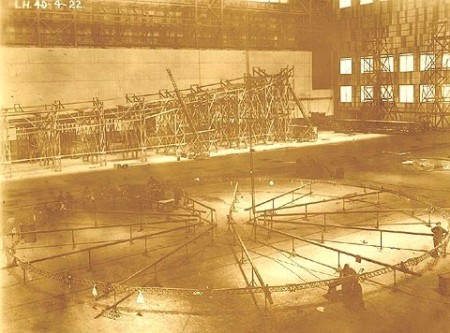

In 1922-23, the U.S.

Navy's first commissioned rigid airship, USS Shenandoah (ZR-1), was

assembled inside Hangar No. 1 at NAS Lakehurst. The parts were fabricated

at the naval aircraft factory (NAF) at Philadelphia and were transported

to Lakehurst by truck and by rail. The first ring or frame, from midship,

reached the base in late April 1922. This was quickly assembled on the

hangar deck and , on 24 April 1922, was hoisted into a vertical position

and supported from below. The ship's frame now grew rapidly forward and

aft. The hull of a rigid airship was composed of alternately spaced main

and intermediate rings or frames connected by longitudinal girders.

The rings were assembled in jigs on the hangar deck

At the base of the framework a triangular cross section of

girders formed the keel of the ship.

The concentrated weights

(fuel, ballast, and other useful loads) were distributed along the keel

passageway which ran through the aircraft. Radial and chord wiring

strengthened the frames and kept the individual rings separated and

aligned despite the various static and dynamic loads imposed on the

structure.

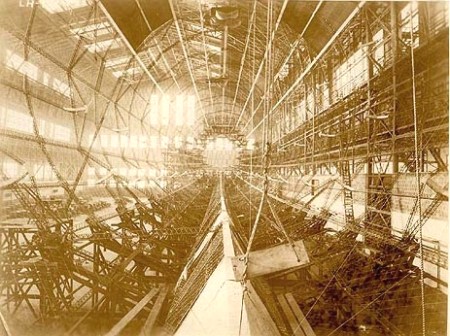

Gradually, the long

cylinder-like hull took shape. By mid-August 1922, eleven of the frames

were in place; by November the hull was about 75 percent complete. The

ship's gas cells were readied for installation. The transverse network

of tensioned wires which gave strength and stability to the rings also

provided bulkheads which divided the hull into ten-meter bays. Here

twenty gas cells were fitted into these, providing the lifting element of

the aircraft. On 23 November 1922, the first cell was lifted into its

bay amidships and test inflated with air to 100 percent fullness.

On 1 February 1923 the

hull structure of ZR-1 was virtually complete. The outer cover was now

applied. Made of high-grade cotton fabric, the cover panels were laced

tightly into place over the entire hull and given several coats of "dope"

which shrunk the material tight against the framework. Sealing strips

doped into place between the individual panels provided a smooth outer

surface over the joints and continuity to the ship's exterior surface.

The final coat was mixed with aluminium powder to provide a smooth,

weather-resistant skin which also reflected the sun's heat away from the

lifting gas.

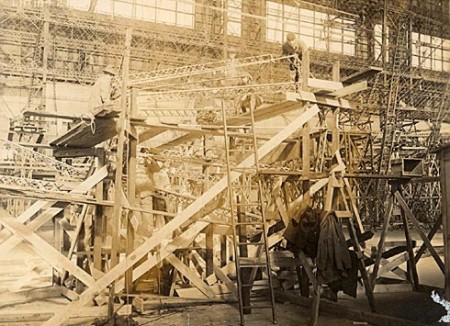

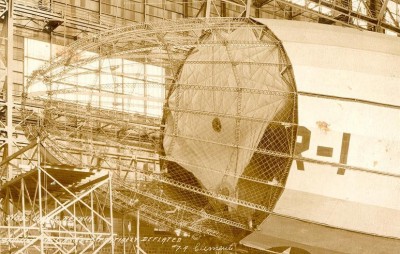

Tail section of USS Shenandoah under construction

General outfitting of the

airship began at this time: the ballast bags spaced along the keelway,

her control wires, fuel and water lines, pumps, and the hundreds of items

of equipment needed to operate the ship. The control car and engine

gondolas also were nearing completion. The six engines were suspended

outside and away from the hull in separate pods. The aft power car and

the control car were equipped with handling rails for ground crews, which

allowed the aircraft to rest on the ground at these two points. The

forward car of ZR-1 was suspended from the hull by struts and cables;

subsequent ships hand theirs built up against the hull. A sixth engine

was located in its own car immediately behind the control car, but his

power plant was later removed.

By mid-June 1923 only the

power plants remained outstanding. Various hangar tests were conducted,

and the aircraft was ready at long last for inflation.

ZR-1 had been designed for

hydrogen, not helium. But the R-38 tragedy in August 1921 had generated

concern about the use of hydrogen, and BuAer (Bureau of Aeronautics) had

recommended that the new ship be inflated instead with inert helium. One

week after R-38, three blimps were destroyed in a hydrogen fire at the

Rockaway Naval Air Station. As one result, the department began

experimenting with helium in its blimp C-7. Then, on 21 February 1922,

the army's semi rigid airship Roma burned in a hydrogen fire

which killed thirty-four of the forty-five men aboard. This was enough.

Official as well as public sentiment to use helium as the lifting gas

became overwhelming.

Original crew of the USS Shenandoah

Four days after her

inflation, on 20 August, ZR-1 was officially "launched". After sounding

general quarters on the power house whistle, and with her full flight crew

on board, 278 ground crewmen took their stations along the hull at the

handling lines. The suspensions to the overhead were cast off, water

ballast was dropped forward, and the ship's bow rose off the shoring,

which then was removed. Ballast was released aft and the men inside

ordered forward along the keel corridor. When the stern was sufficiently

light, the deck force at the after power car lifted her free of the

shoring aft. At 1434 hours, ZR-1 was floating free. The 680-foot

aircraft was walked to the south side of the big room and placed onto

cradles beneath the control car and after power car. The first U.S. rigid

airship had been launched.

In the late afternoon of 4

September, with fifteen thousand spectators, dignitaries, reporters, and

newsreel people on board the base, ZR-1 was walked out for the first

time. This demanding operation required 420 sailors, marines, and station

civilian employees. Primitive mechanical equipment assisted the

struggling ground crew, but significant improvements in ground handling

were five years in the future.

When well clear of the

hangar on the West Field, and after being allowed to swing into the wind,

the new ship lifted off the field at 1720 with twenty-nine aboard. This

local flight was the first ever by a helium-inflated rigid airship. Only

four of her engines were used and these were run at one-half speed. The

airship was landed after fifty-five minutes aloft.

Shenandoah's christening

ceremony took place on 10 October 1923. Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby,

his wife, and a party of dignitaries, including Admiral Moffett, were

received on board by the commanding officer with full naval honours. At

1630, Mrs. Denby, as sponsor, christened the new ship USS Shenandoah. The

christening party was then taken onboard for a one-hour flight along with

reporters and newsreel cameramen. Shenandoah now was an operating unit of

the navy. Two days later, the chief of naval operations advised all

commands that "Shenandoah is added to the navy list and assigned for

special duty to the Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, New Jersey."

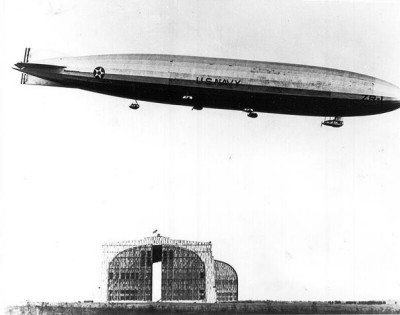

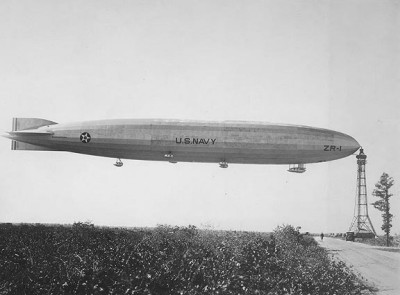

Shenandoah in flight over Hangar No. 1

It was the exuberant

1920's. Among the many obsessions of American culture, science had

quickened its seductive hold. The technology of automobiles, radio, and

aeronautics aroused a special interest in the public. In this optimistic

atmosphere, ZR-1 quickly became the darling of the American press and

public. Publicity flights to show off the new ship to the Northeast and

Midwest tended to dominate Shenandoah's schedule. Indeed, the airship's

seventh flight (1-3 October) was an ambitious forty-eight-hour,

twenty-two-hundred-mile adventure to the St. Louis air races.

Regrettably, these "hand-waving" flights were well removed from the fleet

where, inevitably, the ship and those to follow would have to prove

themselves.

Operations in this period

involved a number of local flights to train with Lakehurst's new mooring

mast. Construction of a permanent mast had begun late in 1921. An area

about 4,000 feet from the hangar's west doors was cleared, and

construction commenced on a 165-foot steel tower to receive and replenish

Shenandoah. By September 1922, the installation was in its final stages.

The machinery house at the base held the main and auxiliary winches for

the mooring lines, along with electric pumps for fuel and for water

ballast, a workbench, an office, and an entrance to the elevator to the

masthead. Quarters for a mast watch were provided for four officers and a

dozen enlisted personnel (enlarged in 1925).

Shenandoah moored to the "high mast" at Lakehurst

The first mast was

impressive. The tower was equipped with three platforms, an elevator,

communication systems, electric lighting (including floodlights for night

operations), and piping for gasoline, oil, helium, and water ballast. A

small elevator ran up the middle of the triangular tower to the first

platform 136 feet above the field. From here a ladder reached the

operating platform 12 feet higher. Communication between this level and

the machinery house was via electric winch telegraphs, voice tubing, and

by telephone. Push-button controls for the pumps were provided. The

third platform, at 160 feet, held the mooring equipment together with

quick couplings for connection to the airship's own lines. Access to the

airship was by gangway let down from the ship's nose to the main

platform. Surrounding the tower on the ground were equal-spaced snatch

block anchorages; lines from the auxiliary winches led through these and

received the ship's two yaw lines let down from her bow.

The virtue of a mast was

the operational flexibility it afforded in terms of independence from a

hangar. A returning airship could postpone docking, for example, if

conditions on the field were unfavourable for this delicate manoeuvre.

Shenandoah used the mast for the first time on 16 November 1923, after

several failed attempts to moor. The entire crew was learning by trial

and error. Two moors were made in December and another two in January,

when extended mooring-out trials began. These tests were intended to

simulate conditions which the ship and crew would experience during the

proposed, and much-discussed, flight to the Arctic via the West Coast.

The polar expedition was

symptomatic of BuAer's posture relative to the large airship. Admiral

Moffett had predicted an Arctic flight in a press conference following the

ship's maiden flight. Indeed, earlier that year, the New York Times

had reported that this new, untried machine would be sent over the

principal cities of America and around the world, as well as visit both

poles! These projections begged reality. The substitution of helium had

reduced the airship's cruising range drastically. The ship's complement

were learning as they flew; the navy had but one large LTA base and, by

1924, was still groping relative to the use of masts. Planning for the

polar hop would finally be halted by President Coolidge in mid-February.

Nonetheless, hostage to the airship's own propaganda and obsessed with

public acceptance, Moffett and the navy "brass" continued to expect far

too much from their large airships, and far too soon.

Extended mast trials began

in preparation for the Arctic hop, when masts would be the only "bases"

available to Shenandoah. Starting on the evening of 12 January, the ship

carried out all operations from the mast. To test the ship in bad

weather, Commander McCrary intended to keep her at the masthead for a week

with a skeleton crew aboard, ready to take to the air if conditions

demanded.

-On the fourteenth, the

aerological office issued an advisory of gale force winds for the

sixteenth and seventeenth. Inasmuch as winds of sixty miles per hour were

wanted for the trial, it was decided to leave the ship on the mast. The

sky clouded over as predicted on the sixteenth, the wind freshened and, by

1500, the airship was rolling slightly but continuously. At 1600, the

watch changed amid driving rain and gusts up to sixty-three miles per

hour. McCrary left the ship at 1700 for his quarters nearby but was

called back by Heinen, who had decided to un-mast and ride out the storm

aloft. But at 1844 a gust of seventy-eight miles per hour struck her on

the starboard bow, destroying the top fin and rolling the hull severely.

The twisting stress wrenched the nose cap free of the ship. The framework

forward was destroyed, deflating the two forward gas cells in the

process.

The aircraft began to

fall. The men on duty in the control car saw the masthead lights

disappearing upward - and knew instantly that the ship had broken

free. Nearby, in the BOQ, an officers' bridge game was abruptly halted.

"...Shenandoah was

gone - she was no longer riding at the mast. We all went dashing over to

the mast through the wind and rain, and there was the nose structure o f

the ship still hanging on the mast along with some heavy mooring gear

from the ship (mooring winches and cable) which had fallen to the

ground. It was obvious that the gas cell in the bow had been torn and

deflated as the ship broke away. -Rear Adm. Calvin M. Boster"

Shenandoah's nose cone was still attached to the mast

after breaking away during the storm

Thus began, according to

Aviation magazine, "one of the most thrilling chapters in the history of

air navigation." Instinctively, hands had reached for the ballast

toggles and forty-two hundred pounds of water were dropped. Men were

ordered aft. Shenandoah drove stern first across the field, nose down.

The ship barely cleared the trees bordering the field and the wild ride,

her twentieth flight, was on. The mechanics on watch in the engine cars

were signalled via the telegraphs and

"...quickly the

engines started in response to the signals; fortunately the controls were

intact. Slowly the personnel gained the upper hand. Up in the bow, the

keel crew struggled frantically to seal the open end, to prevent the rush

of air from destroying cell after cell like a row of dominoes. Weights

had to be shifted, fuel pumped about, to restore the crippled craft to an

even keel." - Lt. Comdr. C. E. Rosendahl, USN

The engines brought a

measure of control, and additional ballast (fuel tanks, tools, and spare

parts) were dropped to restore trim. The ship was allowed to run before

the storm to the northwest. Meanwhile, Lakehurst waited fearfully

without word from the ship. Her radio had been dismantled. Now the

radioman worked feverishly to reassemble the wet and scattered pieces of

his precious set. Finally, at 2100, Shenandoah's first message was

broadcast: "All O.K. Will ride

out the storm. Think we are over New Brunswick. Holding our own. Verify

position and send us weather information. - Pierce"

A reply advised the

ship that she was in fact over Newark, fifty miles north of Lakehurst, and

almost directly over radio station WOR - then located on the top floor of

the downtown Bamberger Building. Commercial stations ceased broadcasting

as WOR announcer Jack Poppele "talked" with the stricken airship and

relayed her reports to Lakehurst until 2200, when direct radio contact was

established. The wind shifted and began to abate. The decision was made

to proceed to Lakehurst, but the ship could not be headed directly into

the wind. Thanks to the damaged fin, moreover, steering remained

difficult. The Shenandoah was slowly nursed back to base. Finally, out

of the gloom, the ship reached the jittery station and "like a crippled

bird" landed at 0330 into the tired hands of four hundred ground crewmen.

Shenandoah received extensive repairs after the breakaway

flight

It had been a wild night

indeed. The gale was one of the worst January storms in fifty years,

causing considerable property damage. At Lakehurst, the high winds blew

down the aerological instrument shelter and blew in some of the

observatory's windows.

The breakaway flight was

the stuff of high drama, and both ship and crew had been worthy of the

trial. The press and public were electrified. The secretary of the navy

congratulated the flight crew. The president also telegrammed his

congratulations for their courage and skill. The Board of Investigation

found no blame or censure for anyone connected with the accident. It

recommended that the mooring device be redesigned to give way before the

airship was damaged. The favourable publicity only further encouraged

Admiral Moffett regarding the proposed Arctic flight, scheduled for June.

Others were far less certain as to the wisdom of the trip. There was

considerable criticism in Congress relative to the navy's proposal, for

example, and serious doubts were expressed in certain aviation circles as

well.

|