|

the Dirigibles

keep coming

Once balloons were

outfitted with propulsion devices and

thus became dirigibles (or airships),

un-powered balloons were

used primarily for upper atmosphere research. In

July 1901, two ambitious

German physicists, Berson and

Surring, established an impressive altitude record of

thirty-five thousand feet (10,668km) that was to

stand for some thirty years.

In the early decade of the

twentieth century, airships

developed along three lines: those that consisted of a

balloon from which the power plant

and the crew quarters dangled were

known as non-rigid; airships with

a skeletal structure

encasing a balloon and to which a crew compartment and

propulsion system were attached

were called semi-rigid;

and airships that were made of a solid

outer shell, with the

passenger and crew compartments

attached and which had balloons inflated inside, were

known as rigid.

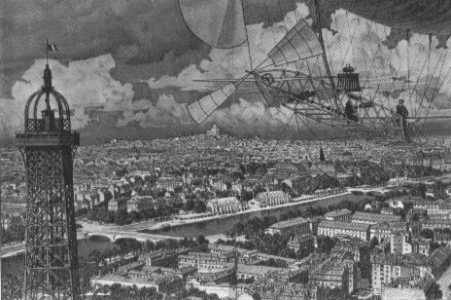

Alberto Santos-Dumont in his signature

floppy hat. The Brazilian aeronaut created a sensation

with

his 1901 flight around the Eiffel Tower, depicted in an

imaginary aerial view by Eugene Grasset.

Prior

to 1904, when he turned his attention to airplanes, the

pre-eminent builder of non-rigid airships was Alberto

Santos-Dumont. His flights over Paris delighted the

citizenry, particularly when a malfunction would result in a

crash, from which the diminutive Brazilian was lucky to

survive. He created a sensation in Paris (and entered

aviation history) when he flew around the Eiffel Tower in

his No. 6 and claimed the Deutsch de la Meurthe Prize

established in 1900. Santos-Dumont used his No. 14 airship

to test his aircraft before his historic flight of 1906.

In the United States, the non-rigid airships being

constructed by Thomas Baldwin were all the rage. The first

aircraft purchased by the U.S. military was a Baldwin

dirigible known as the SC1 Equipped with a Curtiss

motorcycle engine, these machines were easy to transport.

They found great use during World War I when they were used

extensively by the British and French for offshore

antisubmarine patrol.

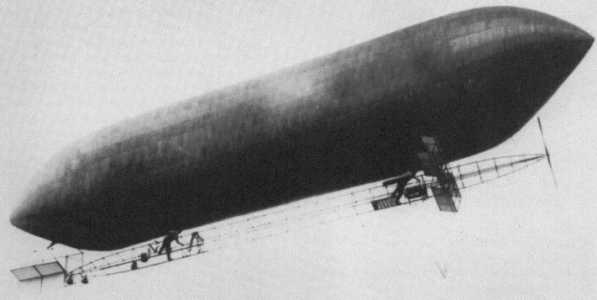

In the first decade of the twentieth century,

experimenters in flight investigated

both heavier- and lighter-than-air machines. Thomas Baldwin

and

Glenn Curtiss test a Baldwin dirigible at Fort Myer on

August 18, 1908.

Semi-rigid airships replaced non-rigid

ones with the improvement of motors and propellers, and a

streamlined design boosted speed. Several successful

semi-rigid airships were built by Paul and Pierre Lebaudy

before 1910, and they performed so well that several

governments ordered them for their fleets. A typical Lebaudy

airship might be two hundred feet (61m) long and thirty feet

(9m) in diameter, powered by engines of 70 to 100 horse-

power, carrying a crew of four, and capable of covering

distances of several hundred miles at a clip of

forty-five to fifty miles per hour.

In England, the

flamboyant American aerial showman Samuel E Cody teamed up

with aerialist Colonel J.E. Capper to build the Nulli

Secundus (“Second to None”), a semi-rigid airship

that amazed Londoners in flights on October 5, 1907, and

became a popular attraction when exhibited at the Crystal

Palace. (The airship was torn apart just five days into the

exhibit, however.)

The semi-rigid airships were abandoned

after 1911, but only because German rigid airships performed

so much better. In the United States, semi-rigid airships

did not fare so well: The America, a semi-rigid dirigible

built by Walter Wellman, made two failed attempts to reach

the North Pole and went down in the ocean during a 1906

attempt to cross the Atlantic. The crew was rescued, but one

of them, Melville Vaniman, decided to try again. His ship,

the Akron, caught fire and crashed off the coast of Atlantic

City, New Jersey, on July 2, 1912, killing Vaniman and his

crew of four.

The era of the rigid airships is easy to

pinpoint: it begins on July 2, 1900, with the flight of the Luftschiff Zeppelin 1 (LZ 1), over Lake Constance, Germany,

and it ends with the Hindenburg disaster on May 5, 1937.

Count Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin had been an observer of

the use of military balloons during the American Civil War,

and soon became convinced that large dirigibles would be an

effective means of air transportation.

The LZ 1, designed by chief engineer

Ludwig Durr, was 420 feet (128m) long and thirty-eight feet

(11 .5m) in diameter, with sixteen internal cells for

lifting gas encased in a shell of aluminium and cotton.

The dirigibles built by Zeppelin’s company, DELAG, from LZ 1

to LZ 129 (the Hindenburg) varied in details, but they were

all modelled on the principles established by the first one.

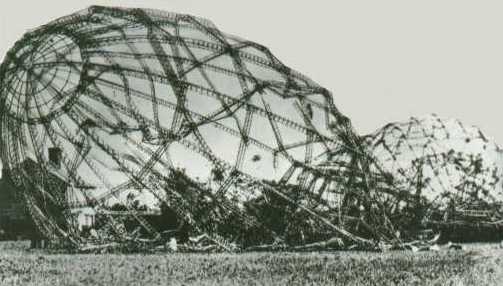

remains of the L33 during WW1

In the years prior to World War I,

five DELAG Zeppelins (for by now the name had become

synonymous with the aircraft) carried some thirty-five

thousand passengers over long distances without mishap. The

only fatalities were incurred in late 1913 when the two

airships were on military missions. During World War I,

Germany built more than one hundred airships for the purpose

of bombing London, but these were no match even for the

primitive fighters the British sent up against them. It was

just as well, then, that the British rigid airship program

never got off the ground. Its one attempt, the Vickers May

fly, designed to be the largest then aloft (at 510 feet

[155.5mj long), was torn apart by a strong wind as it was

taken out of its hangar for a test flight.

|