|

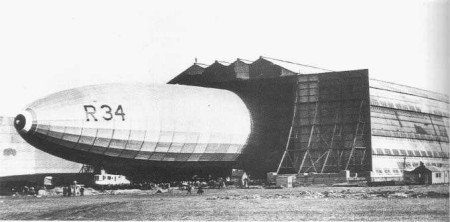

The R 34

edited from the

Airship Heritage Trust

To the members of her

crew, His Majesty's Airship R.34 was known as 'Tiny' - inevitably. The

ship was enormous: as big as a contemporary 'Dreadnought' battleship.

Her overall length from bow to stern was 643 ft, twice as long as a

football field; her maximum diameter was 79 ft and her overall height

just short of 92 ft. Her cost was around £350,000 and her total gas

capacity was 1,950,000 cubic ft, giving a gross lift of about 59 tons

and a disposable lift, when the weight of the structure and permanent

fittings was discounted, of 26 tons. Like her sister ship, five engines

were fitted, each of 250 h.p.

At the time, German technical development had been kept a close watch

on and R.34, in particular, had departed from the engine plan of L.33

to follow instead that of the later and more advanced L.49, which had

been forced to land in France in October 1917. The former ship had

boasted six engines: one to each of the three forward propellers, one

to the rear propeller and two driving small 'wing' propellers by shaft.

On the latter vessel, the designers had done away with this cumbersome

arrangement, eliminating one engine and the two wing propellers

entirely, harnessing the power of two rear engines to a single enlarged

propeller.

|

Statistics:

|

| Length |

643ft |

| Diameter |

79ft |

| Speed

|

62mph |

| Engines |

5 x 270hp |

| Volume |

1, 950, 000cft |

Construction began at

the Beardmore Inchinnan airship factory in 1918 . The whole framework

was varnished to prevent atmospheric corrosion and heavily braced by

wiring.. Lengths of linen fabric were stretched between each pair of

frames, where they were attached by laces. Narrow strips were then

glued over the lacing and the covering of the hull was painted with

dope containing aluminium powder, to reflect sunlight and so reduce

superheating. In the chambers formed by the main circumferential frames

and the longitudinal girders were the gasbags, nineteen in all and made

of one thickness of rubber-proofed cotton cloth, varnished and lined

with goldbeaters' skins. Each gasbag was contoured to fill all the

available space and was surrounded by cord mesh to prevent chafing

against the girders. Following the same design as the R33, beneath the

main body of the airship, suspended by long, wooden struts and braced

rigging wires, were four small gondolas.

As designed in the R33, the forward gondola, some fifty feet long and

although to outward appearances a single unit, was actually made up of

two parts separated by a narrow gap, intended to prevent vibration from

the engine affecting the W .T. equipment. Incorporated in the forward

section were a control room and a small wireless cabin, below which,

during flight, trailed a long aerial. The control cabin, which was

fronted with 'Triplex' safety glass and had handling rails mounted on

each side. Here were the steering and elevator wheels the gas-valve

controls, the engine telegraph, the various navigational and WT

instruments, and the toggles controlling the emergency forward water

ballast. Connecting control-cabin with the keel was a ladder, protected

from the elements by a streamlined canvas cover. Another cover

similarly enclosed the numerous control-wires connections that led up

into the hull. In the rear section of the forward gondola was the first

of the engines, driving a single pusher propeller 17-ft in diameter. In

the middle of the lower hull amidships were the two smaller 'wing'

gondolas, housing an engine together with reversing gear -a refinement

that enabled the airship, which could be operated if those in the main

control-cabin failed. The rear car was ringed with a rail to assist

handlers, and as with the forward gondola, two 'bumping bags' of

compressed air were positioned underneath to help cushion landing

shocks.

Each of the five engines was a Sunbeam 'Maori': a new type, designed

for the Wolverhampton firm by a Frenchman, Louis Coatalen and intended

specifically for airship use, but clearly inferior to the Rolls Royce

engines used by earlier British rigids. Unfortunately, no Rolls Royce

engines could be made available, as all those produced were now

reserved for aeroplane use, and the Sunbeams had been accepted

reluctantly. Each engine had twelve water- cooled cylinders, which were

intended to produce full power at a theoretical 2,100 r.p.m., although

in practice, it was rare for 1,600 r .p.m. to be exceeded. In the

forward and wing cars, the radiators were mounted externally and

controlled by folding shutters. The after gondola of R.34, containing

two engines geared to one propeller.

The engines were each fitted with a hand starter, while the drive to

the propellers was through a sliding dog-clutch, a Hele Shaw clutch and

a reduction gearbox with a ratio of 1 : 3.86. The clutch enabled the

engine to be started and warmed up before flight without incurring

danger to the handling-party, and made it easier to carry out repairs

in the air. If the engine should be stopped during flight, the

disconnected propeller could rotate freely in the air stream to reduce

head resistance, although if it was required to remain stationary for

landing or any other reason, a special brake was provided for this

purpose. Assuming that the airship was still moving forwards, the

engine might then be started by releasing the brake and engaging the

clutch again.

In addition to the gondolas, a considerable amount of space was

available also inside the hull and invisible to the outside observer.

Running almost the entire length of the ship was a long keel corridor,

consisting of a succession of A-shaped frames standing on the two

lowest girders, and with three auxiliary longitudinal girders of their

own to fence off the surrounding gasbags. At its widest part, this

corridor was about 10 ft across, narrowing somewhat towards the

extremities. Leading to the wing and after cars were narrow ladders,

fully exposed to the force of the elements. It had been discovered

following tests on R.33 that the turning co-efficient of the two

airships was 6.4 , giving a minimum turning circle some 4,100 ft in

diameter. However, so strong was the effect of the slipstream of the

after propeller acting on the rudder, that with the forward engine

still and the wing propellers both running in reverse, it was possible

to pivot either ship on herself.

Designed slimmer than the theoretical ideal, the aerodynamic shape of

R.34 was a distinct improvement on most earlier designs -her total air

resistance being only seven per cent of a hypothetical flat disc of the

same diameter. In later airships, this was reduced even further, but in

her own day the streamlining of R.34 was excellent and twice as

effective as that of her British predecessors. Even though the R34 was

designed during a time of war, the R.34 was never fitted with a full

armament. In addition to bomb racks, the original plan had been to

include a ventral 'gun house' behind the rear car, which would carry a

one-pounder Pom-Pom and two Lewis machine guns. Another Lewis gun was

to be mounted on the rear platform behind the tail, while six more were

to be shared equally among the two wing-cars, the forward gondola and

the top gun platform. Further arsenal of weapons included a two-pounder

quick-firing gun was to be placed on each side of the hull and two more

were to join the Lewis guns on top. This heavy armament, which was

presumably intended for defence against German zeppelins, and in the

event the gun house was never fitted and the number of guns

considerably, reduced. The original spec showed that her bomb-load was

quite considerable: twenty at 100 lb and four at 550 lb.

The firm of William Beardmore and Company Ltd. , of Inchinnan, near

Glasgow, began work on R.34 on 9 December 1917 and she was completed

just over a year later on. By the time R.34 was ready for her test

flights, the war was over and she was too late to see active service.

But on 30th December, while bad weather delayed the trial flight,

Admiralty agreed to lend their airships to the Air Ministry for

long-distance trials. R.34 was specifically mentioned. Preparations

H.M.A.R.34 was completed in December 1918 and her lift and trim trials

were carried out successfully on the 20th of that month. But because of

the persistently bad weather it was not until the following March that

she left her hangar at lnchinnan, near Glasgow, where the Beardmore

Company had their works.

On 14 March, R.34 was

brought out from her hangar and her crew began the task of accustoming

themselves on the ship. The maiden flight lasting nearly five hours,

was uneventful and the ship was returned safely to her shed. On 24th

March, despite cold, windy conditions with intermittent fog, snow and

hail, R.34 left lnchinnan in the late afternoon for a more extended

trial. She flew down the Clyde, and then turned to fly over the North

of England, towards Newcastle, then turned and returned via Liverpool,

over the Irish Sea to Dublin, and returned via the Isle of Man. During

this trial it was discovered that her elevator had jammed down, lifting

the nose up, after bringing the ship to an even keel, the ship was

nursed home to Scotland. No real damage had been done, but on return on

the base, the ship was badly handled by the ground crew, which caused

damage to her propellers and some of the main girders. The damage

caused the ship to be laid up to be repaired, it was this incident

which caused the delay in the trip to the USA, and hence loosing the

title of the "first to cross the Atlantic" to Alcock and Brown. The

R34 was ready for service again at 6.00pm on 28th May and the ship left

Inchinnan for her new home of East Fortune, the main airship base on

the Firth of Forth. The R34 was enveloped in fog and so headed out to

sea to wait an improvement in the landing conditions . The ship had to

wait longer than expected and finally landed at 3.30pm the next

afternoon, the crew hungry after 21 hours as no food had been carried

on board this flight. The plans for the transatlantic voyage were

hurried forward . Two weeks after arriving at East Fortune, the R34

flew with the R29 over Edinburgh and Berwick. This short 6-hour flight

was to confirm the stability of the ship. On the evening of the 17th

June 1919 the R34 was sent on an endurance voyage to give her a proper

test before her major flight. The idea was that the ship would be

scouting the German Baltic Shores. The ship carried out its duties and

also flew up to Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The ship landed after this

endurance trial on the morning of the 20th June after a trip of 54

hours.

The Air Ministry had now finally decided to take the R34 to the USA,

and a northerly coastal route was decided in case the ship ran out of

fuel, then she would never be too far from landfall. Two warships, the

Renown and Tiger were offered as supply vessels in case the ship would

come in to difficulty and also to offer meteorological reports. It was

agreed that if the ship did get in to difficulty, then the R34 would be

taken in tow. The plans which were being arranged in New York were the

supply of hydrogen for the ship, and a party of 8 experienced airmen

were dispatched to America to arrange and train the main part of the

American ground crew. The American s had at that time, no experience of

a rigid airship.

At the Admiralty, a room was set a side for wireless messages. A map

was also provided for the ship's progress. At East Fortune, further

alterations were being made to the ship itself for the voyage. Food

lockers replaced bomb racks, which had been installed at her

construction, and a compass was placed on the upper gun platform in

order that the magnetic field would not be interfered with by any of

the electrical equipment. Additional tables and new wash basins were

added in the crew space, and furnished with lightweight curtains to

stop the drafts from the interior of the hull. Along the keel an

additional 24 petrol tanks were fitted bringing the total fuel capacity

to some 6,000 gallons.

The crew were divided

in to two watches for the trip. In addition to the RNAS uniforms, the

crew was issued with heavy duty flying suits, which were redesigned to

include parachute harnesses and integral life saving collars.

On 1st July 1921 the ship was gassed to its limit and loaded to its

full capacity, and by the end of the evening the ship was ready to go.

The ships official departure time was set at 2.00am (GMT) on 2nd July

in order to obtain the maximum lift from her gasbags. The ship was

eased out of her shed slowly by 700 members of the handling party. The

weather forecast was favourable and Major Scott decided not to wait any

longer, and at 1.42 am (GMT) the signal to release was given and the

R34 lifted slowly in to the misty night sky.

The engines were signalled to commence and the propellers roared into

life. The ship was on the way to America, but was so loaded for the

journey, that even with the forward momentum of the engines, she very

slowly gained height. The R34 travelled along the Firth of Forth, then

at a height of 1,300ft she cleared Rosyth, Glasgow, and down the Clyde

by daybreak.

Life on board began to settle in to routine of the agreed scheduled

watches, meals and rest times. Strains of jazz could be heard through

the ship from the gramophone , which was carried on board for the

entertainment of the crew. Crossing the ocean, the morning fog lifted

and the crew saw that they were stuck between two cloud layers, the

upper obscuring the sun. The wireless operators were finding that these

weather conditions were causing electrostatic shocks from the

equipment. The clouds soon parted and the sun broke through. Major

Scott was wary of the effect of superheating on the gasbags, and wanted

to avoid at all costs the valving of hydrogen at this early stage of

the flight, and so he bought the ship down low into the layer of fog,

which protected the ship from the sunshine and soon cooled the gas. The

ship carried on with her voyage at a steady pace, and standard

routines.

The main upset occurred at 2.00pm on the first day. It was discovered

that a stowaway had managed to creep on board the ship, and hide up

in-between the girders and the gasbags inside the hull of the ship.

Before starting on the voyage, it was decided that some of the members

of the crew, including W.W. Ballantyne , must be left behind, the

numbers being limited of necessity to thirty on the voyage. Two hours

before the flight, William Ballantyne managed to climb back on board

the ship, and hid himself in the darkness of the ship. He had also

carried with him, the crews' mascot, a small tabby kitten called "Whoopsie".

Both of these stowaways had hidden themselves. But the cramped

conditions and the fact that the smell of the gas had made Ballantyne

nauseous, made him give up and come out of hiding.

The dishevelled stowaway was brought in front of Major Scott and

Maitland, and it was decided that there was actually nothing they could

do about it. It was agreed that had they been over land then Ballantyne

would have been put overboard by parachute, but as the next landfall

was in fact America, he was to stay on board. The only problem that

could occur was the strain on the very limited and controlled

resources. Having been quite ill for some time, he was rested on one of

the hammocks, and attended to by Lieutenant Luck. When he recovered,

Ballantyne was, as with traditional stowaways, made to work his passage

as cook and often having to hand pump the petrol into the tanks. As to

the second stowaway, Whoopsie, it was deemed that the oldest airman on

board, 42 year old George Graham accepted responsibility for the cat,

and Whoopsie worked her passage throughout the rest of the voyage,

providing entertainment and comfort to the other crew members.

The weather slowly worsened, and all the ships engines were engaged to

full power as the wind speed increased and a storm began to approach.

The next morning the R34 was halfway across the Atlantic but the

weather was continuing to deteriorate. However throughout the day there

were some breaks in the weather causing the ship to be able to view the

transatlantic shipping traffic below, for some 50 miles in each

direction. By the evening the weather became increasing stormy and the

wind turned head on to the ship. Coming up from the southeast, the

winds were blowing at about 50mph causing the ship to fight her way

forwards and sideways.

Throughout the night, Major Scott tried to move the ship up higher to

avoid the wind, but if was found to be the same at each level. By

morning the cloudbank had moved away and clear skies brought a sight of

a 150ft iceberg below the ship, further behind it smaller bergs and

pack ice was visible. The clouds soon returned as Newfoundland was not

far off the ship, and fog enveloped the ship once more. Concern was

beginning to show by Major Scott as there were no gauges on the petrol

tanks and use of the dipstick showed that there were only some 2,200

gallons of petrol left. With further strong headwinds expected down the

coast, the thought of getting to New York without stopping was looking

more unlikely every hour that drew on.

The ship flew over Labrador and at 12.50 the land was sighted for the

first time. Now the ship had to follow the coast down and head for it's

landing place at New York. With only 500 gallons of fuel left, the ship

was bought down to 800ft to try and escape the worst of the headwinds.

From this height, the crew had superb views of the North American

forests and could see, smell and hear every detail. The ship had been

in the air for 4 days and the crew was beginning to tire. Emergency

preparations were tentatively being made in Boston for emergency

landing there, but the ship continued on her voyage. Each fuel tank was

inspected and whatever was left in the bottom of the tanks was

collected and poured in to the main tanks to keep the engines running.

Major Scott made the decision to continue onto the agreed landing area

at Mineola, Long Island, New York. In the last hour of the flight, the

crew busied themselves in making themselves presentable.

By 9.00am Mineola came in to view. All the car parks were full and a

huge grandstand had been erected for local and national dignitaries.

Major Pritchard donned a parachute and whilst the ship circled

overhead, dropped to the ground and became the first man to arrive in

America by air. He hastily arranged the ground crews, and helped ease

the ship to the ground. The R34 landed at 9.54am after 108 hours 12

minutes flying time. This became the world endurance record breaking

that set previously by the British NS 11. There were 140 gallons of

fuel left on board, which was sufficient only for another 2 hours

flying at reduced power.

The ship was only in America for 3 days. During this time the crew were

allowed to rest and have hot showers, they attended a constant series

of events where they were saluted for their historic crossing. The

people of New York lavished their generosity on the crew and they were

bombarded with offers of invitations to formal functions during their

stay. The engineering crew stayed with the ship ready to give the

engines a long-awaited overhaul and a full check over in preparation

for their return voyage home. It was found that that no repairs were

necessary and the engines had performed well. The propellers had

accumulated a thick coating of engine oil and this was proudly removed

by a local firm, free of charge and just happy to offer assistance to

the crew and to the ship.

The R34 was in very good shape, and moored to a three-wire system at

the bows, whose own lift kept the wires taut. The crew returned to the

ship and provisions were loaded back onto the ship for her return

voyage. The final preparation was to gas the ship, and this was carried

out using thousands of cylinders of hydrogen gas. As with the flight to

America, the R34 would be gassed to capacity again, and await the

coolest part of the day to depart, and so the ship was finally launched

at 6 minutes to midnight on Wednesday July 10th. The great crowd which

had always been around the R34 her entire time in America gave a huge

cheer, and the ship was launched.

The wind had picked up before the launch and was gusting at 30mph,

which caused concern, but the ship cleared the landing field, and made

her way eastwards. As a gesture of gratitude to the city, which had

generously hosted her crews, the R34 flew towards the illuminated

metropolis. The ship made her way up to a height of 2,000ft as Major

Scott was unsure of the height of the skyscrapers. Searchlights

illuminated the ship as she flew over the city and, despite it being

1.00am in the morning; thousands of well wishers took to the city

streets and rooftops to wave. The ship then turned out to the sea and

headed on towards home.

Very good progress was made during the night as the ship had the

advantage of a strong tail wind, and her speed increased to 90mph as

she flew in the prevailing air current. The forward engine was rested

and still the ship was managing to race along at 90 mph. The crew was

unprepared for the swiftness of their eastward crossing of the

Atlantic. It was considered that, as the R 34 was gaining time on her

voyage and not expending much of her fuel compared to her outward

journey, the ship change her flight route and fly over London before

returning to East Fortune. The return home was uneventful, and the

standard ship routine continued. The only problem occurred when an

engineer fell against the clutch of an engine causing the engine to be

freed and race until destruction because the connecting rods fractured.

The repairs could not be made in flight and so the engine was stopped,

but this in no way impeded the speed of the ship. Due to this event and

not having any spare power in case of emergencies, it was decided to

cancel the voyage over London and head straight home. It was not until

the final evening at midnight when a message was received from the Air

Ministry to divert the ship from landing at East Fortune, but go

directly to Pulham. It was initially due to bad weather at East

Fortune, but a few hours later a message from East Fortune confirmed

the weather conditions had improved. A request was put in to the Air

Ministry to have the ship return to East Fortune but this was turned

down and the ship was ordered to Pulham. No reason was ever given for

this change in plan and no explanation can be found for it. The ship

carried across the English countryside and came, rather quietly to

Pulham Air Station at 6.57 GMT to be welcomed by the RAF personnel,

which was rather quieter than that which greeted the ship at New York,

and than expected at East Fortune.

The return journey had

taken three days three hours and three minutes. The ship had travelled

some 7,420 miles on this voyage at an average speed of 43 mph.

|