|

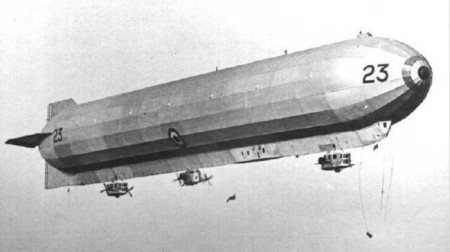

The HMA 23

edited from the

Airship Heritage Trust

Following the success

of HMA No. 9 further ships were ordered by the Admiralty. Along with

the Vickers Company, three new contractors, were required to produce

rigid ships. The Vickers Company had already proven themselves with the

design and construction of No. 9 and were the only company with any

experience of building a large ship.

Following the trials

and design success of HMA No. 9 it was agreed that the Zeppelin threat

had to be tackled head on and decided that further ships were required

by the Admiralty. There were initial problems at the Admiralty with

regards to change of staff and also general opinion regarding rigid

airships, as the successful non-rigid programme was expanding rapidly .

However in June of 1915 along with the Vickers Company, three new

contractors, were required to produce rigid ships. The Vickers Company

had already proven themselves with the design and construction of No. 9

and were the only company with any experience of building a large ship.

|

Statistics:

|

|

Length |

535ft |

|

Diameter |

53ft |

|

Speed

|

52mph |

|

Engines |

4 x 250hp |

|

Volume |

942, 000cft |

The three new

contractors were Beardmore, Armstrong and Whitworth and finally Shorts

Brothers. All three companies were to become famous in the world of

aviation. By October 1915 the drawings were approved and three ships

were ordered. By December the pace of design and the requirement for

big ships had increased dramatically, and a further sixteen ships had

been budgeted for by the Admiralty. All of these ships were to become

known as the 23 Class which were in effect stretched versions of the

original No. 9. The designs were seen in essence as modified versions

of No.9 with an extra bay inserted in the middle of the ship. A gun

platform was added to the top of the ship designed to take a 2lb gun

and two Lewis Machine Guns.. The platform was surrounded by 18 inch

sanctions carrying life lines. These sanctions could be extended to

double the height in order to carry a canvas windscreen. Three other

Lewis guns were to be fitted at the extreme tail, in the control car

further aft and on the top walking way.

The bomb load was to be greater than that of HMA 9 but none was

actually specified. The ships each possessed an external keel, to the

same pattern as the No. 9. The cabin being 45ft long contain crew

accommodation, a wireless room an bomb room. From the keel further aft

were three gondolas which were suspended below and accessible by open

ladders. The ship gondolas also contained airtight buoyancy bags in

case the ships had to alight on to water. This was a technical

requirement of all ships since HMA 1 - the Mayfly. With this rapid

expansion of the requirement for airship production, there were a few

problems with the fact that so far, only one Company had actually build

a ship and hence had all the facilities.

However to help the others Vickers provided components to the other

three companies to assist in production. The original ships were

devised out between the various contractors and the registrations were

allocated between them :-

H.M.A 23 - Vickers

H.M.A 24 - Beardmore

H.M.A 25 - Armstrong Whitworth

H.M.A. R26 - Vickers

In April 1916 the

Government approved for a total fleet of 10, 23 class ships, but this

was later modified in the light of further design technology and

competition available from Germany. The later ships becoming the R23X

class, and the R31 class.

The HMA 23 was the first to be completed, and hence the designation of

the class of ships. There were a number of delays in the initial

constrictions and the ship was completed on 26th August 1917. This lead

to the order of the R26 as Vickers had the space available to build the

ship. On lift and trim trials, the HMA 23 was found to have a

disposable lift of only 5.7 tons, due to the machinery being two tons

heavier than originally estimated. Five weeks later the HMA 25 was

completed and her tests gave her almost identical results. Although not

unexpected the figures were disappointing, and 2 weeks later on the

18th October the Admiralty decided that the design must be altered. On

the day of the decision the HMA 24 was also tested and found to be

mysteriously two thirds of a ton heavier than her sister ships, with a

lift of only 5.1 tons. The alterations to the ships included the

removal of dynamos and bomb frames and many other items which were

deemed not necessary, were removed. Upon inspection of No. 24 it was

later found that the ship was heavier due to having used rivets,

fastenings and bracing pieces which were slightly larger and heavier

than originally expected and hence increased the overall weight of the

ship.

The Admiralty ordered that

modifications be carried out at once to R.26, which was still in the

early stages of construction, while the other three ships were to be

modified similarly but, of necessity, over a longer period and slightly

less drastically. The measures to be undertaken were aimed at

lightening the airships by the elimination of all unnecessary weight

and included the removal of the dynamos, buffer wheels and bomb frames.

Many other small items not considered essential were either taken out

or replaced with lighter equipment. The folding tables which had been

intended for the keel cabin were never installed, and the original plan

of fitting a two-pounder gun on the top platform was also discarded.

The rear car was replaced by a smaller and lighter one containing an

engine with direct drive to a single two-bladed propeller 13 feet 6

inches in diameter. As there was now no space for the auxiliary

controls, these were transferred to the keel cabin.

Some of these

modifications had already been carried out on the first three ships,

while others followed in due course. Together they effected a marked,

if not substantial, improvement to the airships' performance. No 24

required more than minor modifications, since she was so much heavier

than the other ships. As Beardmore's shed was needed immediately for

the building of R.34 it was necessary to move the ship to her new

station at East Fortune as soon as possible. This required extra lift

to enable her to fly safely over the hilly countryside of southern

Scotland, so in addition to the changes already made the drastic step

was taken of removing all the machinery from the after car-engine,

propeller, radiator and silencers. All these modifications brought the

disposable lift up to nearly 61/2 tons, but the price paid was a top

speed barely in excess of 35 mph. In this form No 24 was delivered in

October , 1917. No 25 was delivered in the same month, but R.26, on

which Vickers could not begin work until No 9 had left Barrow, arrived

much later. All the recommended modifications were incorporated in the

course of her construction tion. Although built more quickly than the

others, in only about a year, she did not fly until March, 1918.

HMA No 23

All four of the 23 class airships were flown extensively, but although

rather more efficient than No 9 they still did not provide the

performance which had been hoped for. No 23 herself had been

commissioned on 15th October, 1917, and left on that day for Pulham.

She had a top speed of 52 mph and flew a total of 8,426 miles in 321

hours 30 minutes. Although she carried out some patrols, usually under

the command of Captain I. C. Little, she was used mainly for training

and experimental work. Trials were undertaken in January, 1918, at

Pulham with a two-pounder gun in its mounting on the top platform of No

23 during the trials at Pulham. The gas valves were placed on either

side of the hull rather than at the top to avoid risk of escaping gas

being ignited during firing.

Six shells were fired with the gun pointing downwards, but instead of

embedding themselves in the mud of the airfield, as expected, they seem

to have ricochet rough the surrounding countryside. The airship took

the strain well, although some flexibility was present, which would

have adversely affected aiming under combat conditions. No further

action was taken in the matter because of the ever present weight

problem. Later in 1918 No 23 was involved in another experiment, this

time to determine whether an aeroplane could be carried by an airship

and released in midair either to repel attackers or to take offensive

action on its own account. A Sopwith Camel was suspended beneath the

envelope by specially prepared :slings. For the first trial a dummy was

placed in the cockpit and the controls were locked. As the airship flew

over Pulham air station the aeroplane was released; it glided to the

ground, showing that the slipping gear operated correctly. Another

Camel was then taken up, this time piloted by Lieutenant E. Keys. As

the aeroplane left No 23 the pilot had no trouble in starting the

engine; he pulled out of the dive to fly around the airship before

landing safely.

No provision had been

made for retrieval during flight, as the intention was that the

aeroplane should make its own return to base after being in action. As

with other unusual projects tried out during the war, nothing further

was attempted. However, similar trials were held after the war with

R.33, and the method was eventually perfected by the Americans in the

early nineteen-thirties. A noteworthy departure from routine training

and testing befell No 23 on 6th December, 1917, when she was sent to

make an unannounced daylight flight over London, arriving out of the

mist from Pulham around midday. At a low altitude she circled over

Buckingham Palace, Whitehall and the City, where thousands of Londoners

clearly saw the lights twinkling in her gondolas, the red, white and

blue roundels on her envelope and her designation numerals. Wartime

censorship allowed press reports of the incident (" At last. ..a

British Zeppelin"), but the airship's number could not be published,

despite its having been so publicly displayed! Twice in the following

year No 23 flew again over London, on one occasion accompanied by R.26,

but these appear to have been the high points in an otherwise mundane

and unwarlike career. She was deleted in September, 1919.

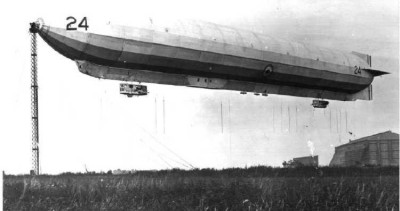

HMA No 24

Her sister ship No 24

had a similar history, flying a total of 164 hours 40 minutes and

covering 4,200 miles, but as the original intention of replacing her

missing engine in a new and lighter car was never carried out she

remained very slow. On one typical occasion, encountering an

unexpectedly strong adverse wind near the Bass Rock, she remained for

some time stationary, quite unable to make any headway. Despite this

severe handicap she was used for training and convoy duties when

conditions were deemed suitable, although she appears to have seen no

action. She made her last wartime flight in June, 1918, but was

retained in service and two months later had her bows strengthened to

adapt her for mooring trials at Pulham, where Vickers were building a

new type of high mast.

The tests, which were carried out with both midship engines removed,

were quite successful but were not completed finally until November,

1919. The following month No 24 was deleted and scrapped.

HMA No 25

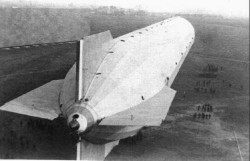

No 25 had been assembled slightly differently from the other three

ships and always suffered from gasbag surging, which caused instability

by moving the centre of lift unpredictably. In spite of this she flew

221 hours 5 minutes in service, covering 5,909 miles. Stationed for

most of her career at Cranwell, she was used mainly for training before

being deleted in September, 1919.

HMA R 26

The last of the class was R.26. (The Admiralty decided on 18th

December, 1917, that all future rigid airships should have the prefix R

before their number.) Apparently the only one of her class to

incorporate all the design changes, she was commissioned on 22nd April,

1918, and stationed at Howden. During tests she was found to have a

disposable lift of 61/4 tons, a top speed of 54 mph and a ceiling of

3,500 feet. It was also discovered that if the engines were stopped at

53 mph the speed fell to 18 mph in two minutes, so great was the drag.

By the end of the year she had flown 191 hours 29 minutes, of which the

highlights were a flight with No 23 over London on 25th October and a

patrol of 40 hours 40 minutes on 4th/5th June, when she was commanded

by Major T . -~. This was the longest flight yet by a British rigid,

beating No 23's previous record, set up a few days earlier, by 32

minutes. Later in the year she was transferred to Pulham and, commanded

by Major Watt, she supervised the surrender of German submarines at

Harwich on 20th November, 1918. In January, 1919, R.26 flew a further 6

hours 18 minutes, and then had her bows specially strengthened before

being experimentally moored out in the open, using the "three wire

system". Despite a tendency to assume a tail up attitude. This was

0vercome by fastening sandbags to the after guys, she survived for over

a week without harm. Then the weather worsened, rain soaked her

envelope and a snowstorm finally beat her into the ground. Her cars

were removed, allowing her to float again, but it was soon found that

the damage she had sustained was too severe for repairs to be

worthwhile. On 24th February the order was given for her to be scrapped

and her official deletion followed on 10th March.

|