|

Despite the problems in 1911 with HMA No. 1 the Mayfly, in 1913 a

decision was made to continue to invest in rigid airships.

Designated as HMA No. 9, a new ship was planned, however when war

broke out on 4th August 1914, this put a delay on further design and

construction of the ship..

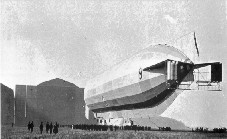

Graphic of HMA No9.

The original plans

for the second rigid Airship had been agreed between the Admiralty

and Government. However, this was a time of turmoil in that the

political situation in Europe had darkened, and also there were

quarrels within the Government as to whether a replacement ship would

be required. The non-rigid programme was proving to be more

successful that the rigid. With the Dardanelle fiasco already making

the situation in Europe more uncertain, a conference was called with

the Admiralty on June 19th 1912 to consider the programme again.

At this meeting it was not only agreed to expand the non-rigid

programme, but also to recommence with the Airship HMA No. 9. It was

agreed that Vickers should be asked to design an improved class ship

incorporating all of the recent knowledge of the Zeppelins. There was

only one restriction with this order, which was that the proposed

classes would have to be built in existing facilities. This meant

that the ship would have to be limited to the size of the Zeppelins

on their cradles in Germany. The reason behind this decision was that

the technology was being based on the German Army Zeppelin Z IV,

which accidentally come to land in France on 3rd April 1913. Her

design was already 3 years old, however there was little else to go

on except the information on what the designers in Germany had

planned. It must not be forgotten that some of the refinements made

were better than that of contemporary Zeppelins.

|

Statistics:

|

Length |

526ft |

Diameter |

53ft |

Speed |

43mph |

Engines |

4 x 180hp |

The rear two engines were replaced by

a Maybach engine retrieved from the wrecked L-33, enhancing the

ships useful life. |

Volume |

846, 000cft |

click to enlarge

Vickers

had disbanded its airship department after the failure of the

government to keep it supplied with work after the Mayfly project. A

new department was therefore constituted in April 1913. They

re-assembled its original design team including H. B. Pratt and the

young Barnes Wallis. Design work started on the No. 9 in April 1913.

Work proceeded slowly at first owing to the fact that the

specifications were required to follow the Zeppelin lines.

The original order for the new rigid was placed on June 10th 1913,

with final plans, which were agreed at the end of the year, and

formal contract signed in March 1914. Construction was delayed by the

fact that the old shed at Cavendish Dock, Barrow-in-Furness was much

too small and so a new one had to be erected. This was completed at

Walney Island, a flat area of land just off the west of

Barrow-in-Furness. The new shed was 450ft long, 150ft wide and 98 ft

high, internal clearances. It also incorporated an innovation having

a 6-inch concrete floor with handling rails embedded in to it that

extended some 450 feet out in to the adjacent field. Also new was the

eight fire extinguishing jets linked to a special reservoir to deal

with the possibility of fire. The gasbag factory with 100 employees

was set up beside the shed.

The

original order for the new rigid was placed on June 10th 1913, with

final plans, which were agreed at the end of the year, and formal

contract signed in March 1914. Construction was delayed by the fact

that the old shed at Cavendish Dock, Barrow-in-Furness was much too

small and so a new one had to be erected. This was completed at

Walney Island, a flat area of land just off the west of

Barrow-in-Furness. The new shed was 450ft long, 150ft wide and 98 ft

high, internal clearances. It also incorporated an innovation having

a 6-inch concrete floor with handling rails embedded in to it that

extended some 450 feet out in to the adjacent field. Also new was the

eight fire extinguishing jets linked to a special reservoir to deal

with the possibility of fire. The gasbag factory with 100 employees

was set up beside the shed.

The

workmen were gathered and by the time of war breaking out, HMA No. 9

was nearly ready for erection. Work on the ship continued during the

first months of the war despite the demand for materials and manpower

due to the war effort. However there were more concerns expressed at

the Admiralty and on March 12th 1915 the first Lord of the Admiralty,

Winston Churchill, cancelled the order for the ship. It was said that

the reasons behind this decision was due to the fact that it was

expected that the war would be finished in 1915 and the vessel would

not be operational by the end of the war, and deemed a waste of

valuable resources. However history proved otherwise, and the war

continued and work was recommenced on the ship with the order

re-instated in June of 1915.

Final erection of the ship began in Autumn of 1915 but the ship

wasn't completed until 28th June 1916. There were problems in

obtaining the nets for the gasbags as the flax was coming in from

Ireland when the Irish Rebellion broke out and hence delayed delivery

of the materials.

On

November 16th 1916, HMA No. 9 left her shed and was moored outside

for final shakedown of the ship, and checking of the fittings and

engines. The first test flight was on 27th November 1916, the first

British Rigid airship to take flight.

With four engines mounted in pairs on each of the two exterior

gondolas, and mounted on massive extension shafts, the designers of

HMA No. 9 had added the useful adaptation of swivelling propellers to

assist in take off and landing. An example of vectored thrust on an

aircraft as early as 1916! This was an idea, which was later used, in

full effect by the Airship Industries Skyship series in the 1980's.

There was a problem in that she was unable to life her contract

weight of 3.1 tons, and so she was lightened by removal of the rear

two engines replacing them with a single engine that had been

recovered from the crashed L33. After this she was able to carry a

disposable lift of 3.8 tons, better than that originally specified.

She left the Vickers facility at Barrow and flew to Howden where she

underwent trials. Most of her life was spent in experimental mooring

and handling tests, as she was still classed as an experimental ship,

as were the first Zeppelin's.

From October 17th 1917 to June 1918 she resided at Pulham Air Station

in Norfolk where she was finally dismantled due to demand for shed

space for construction of newer ships.

HMA No. 9 spent 198 hours 16 minutes in the air, of which some 33

hours were at mast

It must not be

forgotten that HMA No. 9 was the first British rigid airship to fly

and the success of the design, thought unable to compete against

contemporary Zeppelins of the time, proved that the British Admiralty

had a successful prototype. They now also had experience of handling

a rigid airship, and mooring tests, which were to evolve in to a

unique method of mooring ships.

click to enlarge

HMA

No. 9 was designed much stronger than her contemporary German

airships. The Admiralty had insisted that she would have to be

handled by novice crews until some officers and men gained experience

with rigid airships. The ship was also designed, as with the Mayfly,

with watertight cars.

|