|

The Red Baron

and His Flying Circus

The planes Anthony Fokker delivered to the front at the

end of 1916 looked very familiar to the

airmen. Fokker never made a

secret of the fact that he used downed aircraft as models

and improved on designs the Allies

had been kind enough to test in

the field. Out of his factory came

the new crop of such aircraft and they were among

the best and most advanced to fly in the war.

The

Germans portrayed such heroes as Baron Manfred von

Richthofen as larger than life. This photo and others like

it could be

found in nearly every German home during the war.

The first plane the new crop of fliers were given was

not a Fokker (though by this time, Anthony

Fokker had become a virtual

minister of aircraft procurement in the

government), but the

Albatross D LI (later to evolve into

the D LII), a lightweight plywood-frame biplane

fighter with a

powerful 160-horsepower Mercedes engine and

two Spandau machine guns. (At the beginning of

the war, Albatross was the

largest German aircraft builder, supplying 60 percent of the

entire air force. By the war’s

end, it could barely field a few

fighters, and after the war the

company disappeared, appearing

briefly in a failed 1919 attempt

at commercial aviation.) The German fliers

were convinced that these

were the finest machines either side

had produced—or could

produce—until they received the

new planes from Fokker.

Richthofen and his Flying Circus became

famous flying the

Fokkei- Dr I, a triplane that borrowed heavily from the

Sopwith Triplane.

The Dr I could be controlled by only the best

pilots, which

limited its deployment. In the hands of Richthofen, the Dr I

could

zigzag like a large fly, eluding faster planes

The first was the Fokker Dr I, a

triplane modelled after the Sopwith

Triplane (made famous by British ace

Raymond Collishaw, whose

plane was called Black Maria), but

including features of the Sopwith Camel, and

equipped with an additional

wing on the undercarriage for more

manoeuvrability. The Dr I was compact and

agile, presenting a small target that was almost

impossible to hit: a length of

less than nineteen feet (6m), a

wingspan of less than twenty-four feet (7m), and a

top speed of 103 miles per hour

(l66kph), which was not the

fastest in the sky, but more than enough to evade virtually

any attack run.

It was flying this

plane that one ace in particular, Manfred von Richthofen, became a legend

and one of the most famous fliers in history. Manfred vonl

Richthofen was born on Max 2, 1892. to an aristocratic

Silesian family. He grew up to he a handsome young man with

a proud, piercing stare and steely nerves, and soon came to

the attention of Oswald Boelcke, who made him the commander

of Jasta 2, renamed Jagdstaffel Boelcke after the great

ace’s death. Von Richthofen extended Boelcke’s ideas of

teamwork and fostered a unity in the corps that allowed it

to function as a single-minded and single-willed unit.

Von Richthofen was still flying an Albatross D II when he won

his Blue Max after his eighth kill in November 1916 and when

he downed Lanoe Hawker (sometimes called “the British

Boelcke”) on November 23. It was this engagement that

convinced von Richthofen that he needed a fighter with more

agility, even at the expense of speed. By the end of 19 1 6,

VOfl Richthofen had acquired the new Fokker Dr I and he flew

both it and the Albatross II) Ill, as the situation

warranted. After he learned that he had shot down Hawker,

von Richthofen painted his plane red out of joy, giving rise

to a new epithet, the “Red Baron.”

Fighter pilots on

both sides recognized the

special camaraderie

among the aces of the same squadron. This is von Richthofen

and his Jasta

He created a new squadron consisting of

the best fliers in Germany, jasta 11, and the planes began

their operations in earnest in January of 1917. In order to

camouflage which plane was his, all the planes of Jasta 11

were brightly coloured with much red, though it was clear to

most ground observers which airplane was almost entirely

red. (The Germans learned that the bright colours of the

planes had a disorienting effect on gunners and, far from

offering a better target as was feared, gave the pilots a

tactical advantage.)

In order to be close to the front, and as

mobile as possible to avoid Allied bombing, Jasta 11 (men

and planes) were quartered in tents, giving rise to a

nickname for the squadron: “the Flying Circus.” The Red

Baron often landed near the crash site of a fallen enemy to

retrieve a memento. Of all the aces of the war, von

Richthofen may lay claim to having been the most complex,

the most troubled by the war, and the most uncertain of his

role in it. He fought severe headaches and bouts of

depression, and recognized more than most the disparity

between how the war was going in the air and how Germany was

faring on the ground.

By the end of March, the fliers of Jasta

11 were tested and hardened into a cohesive unit that was

invincible in the sky. The month of April 1 917 was one of

the worst for Allied airmen, as Jasta 11 alone accounted for

eighty three victories and 3 1 6 lost airmen. The month

became known as “Bloody April” and the Germans were uncontested

in the skies over the Somme battlefields below. But on

the ground the Germans called 1917 “the turnip year,” as the

embargo of the continent by the British continued to

strangle the Central Powers. It seemed to all that 1918

might be the fateful year in which the war would end.In 1918

Fokker created one more plane, taking the basic design of

the Nieuports and creating the D VII, a biplane thought

today to be the finest all-around fighter of the war, and

the only plane the Allies insisted the Germans relinquish as

a condition of the armistice. But the crash program to turn

out these planes came too late to affect the outcome of the

war.

By 1918 the Allies had recovered from

Bloody April and even von Richthofen’s talents could not

overcome the plodding, methodical, piecemeal conquest of the

skies by the Allies. Manfred von Richthofen met his end in

battle on April 21 1918 probably at the hands of a Canadian

pilot of a Sopwith Camel, Captain A. Roy Brown, though

questions persisted as to exactly how the Red Baron died.

Richtofen, chasing the plane piloted by Captain Brown and

being pursued by a plane piloted by another Canadian,

Lieutenant Wilford May, was caught by a bullet fired by one

or the other of his assailants as he stood and turned to

check the tail of his plane. Having fallen in Allied

territory, the Red Baron was taken from his plane and given

a funeral by the Allies worthy of one of their own fallen

aces—the pallbearers were all captains and squadron

commanders, as Richthofen himself had been.

Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen's medical record--was the "Red

Baron" fit to fly?

Much has been written about the rivalry among the allied forces in World War

I to claim the "honour" of having killed Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen, the

"Red Baron" (1882-1918). This issue is still being debated periodically in

aviation and veterans' magazines 80 years after his death.1,2 Here I

review the Red Baron's military medical record, which has been made available to

me by approval of his next of kin. It raises the question of whether von

Richthofen should have been allowed to fly after having received a head injury

during aerial combat on July 6, 1917.

Cadet von Richthofen

Von Richthofen entered the cadet corps on April 18, 1903, aged almost 11

years. His previous medical record showed a history of measles, chickenpox, and

rubella. Eyesight was examined yearly and remained 6/6 throughout his brief

career.

The medical record for that period is unremarkable with the exception of an

injury to the right knee on June 12, 1909, that required a stay in hospital

until July 3, 1909. A swelling of his right knee led to another short stay in

hospital 1 year later. Surgery was successful and there is no mention of further

knee problems during the remainder of von Richthofen's life.

Military service

Von Richthofen began active military service on May 1, 1911, and served as a

cavalry officer; therefore he was later given the title of Rittmeister

(literally, riding master), the cavalry term for Captain. 4 years later in May

1915, he switched to the newly established flying force with the explicit goal

of becoming a pilot rather than an observer. No mention is made of a medical

examination before entering the German flying service in the autobiographies of

either von Richthofen or of Ernst Udet, another famous fighter pilot of the

period.3,4 There did not seem to be any special requirements or

medical examinations to obtain clearance for flight duty among the guidelines of

that time for troop fitness.5,6

In his book The Red Air Fighter, von Richthofen mentions how he

received his first wound on Sept 4, 1915, while flying on a bombing mission. He

was still in training and therefore sitting in the observer's seat of a bomber.

When he tried to point out where the bombs had hit, he grazed the little finger

of his right hand on the propeller. In his own words, "This did not increase my

fondness for bombing planes". He was grounded for 8 days.3 The

diagnosis in his medical record was "complicated fracture of the right little

finger tip" (figure 1). After initial examination he was transferred to a nearby

naval hospital, where he received tetanus immunisation and his finger was

splinted. The healing process was unremarkable and he was released from hospital

on Sept 10, and declared fit for flying duty.

|

|

|

Figure 1: Drawing of finger wound in medical record

|

Von Richthofen remained healthy until July 6, 1917. Up to that date he had

been credited with bringing down 57 enemy planes, been decorated with the Pour

le Mérite ("Blue Max"), and gained celebrity status in Germany and among the

allied forces. On June 25, 1917, he was made commander of the flying unit

Jagdgeschwader I (literally, hunting wing I), which had been created the day

before (it exists to this day as Jagdgeschwader Richthofen ). At that time the

most successful German ace to survive the war, Udet, was credited with six

victories in air combat; he ended the war with 62 victories on his record.

Wounded

It is interesting to compare the two available accounts of von Richthofen's

crash after he had been shot in the head during aerial combat on July 6, 1917.

There is the version that has been published in his autobiography and the story

as recorded by the physicians in the medical file. In his book, von Richthofen

describes how he was about to attack a Vickers "bomber" and had not even taken

the safety catch off his gun when the bomber's observer started to fire at a

range of 300 m, a distance that von Richthofen considered to be too far away for

"real" combat. In his own words, "the best marksman just does not hit the target

at this distance". Suddenly there was a blow to his head and he was totally

paralysed and blinded. After a great effort he was able to move his limbs again

while sensing that his plane was in a dive; still he could not see. When the

darkness slowly lifted he first checked his altimeter, which showed 800 m, a

drop of 3200 m within a few moments. He reduced his altitude to 50 m and made a

rough landing, when he realised he was going to faint again. He was able to get

out of the plane and collapsed remembering only that he had fallen on a thistle

and had not been able to move from the spot. After a drive of several hours in a

motorcar he was taken to a field hospital.

The history in his medical file is very similar, noting that he did not lose

consciousness in the plane. "His arms fell down, legs moved to the front of the

plane. The flying apparatus fell towards the ground. At the same time he had a

feeling of total blindness and the engine sound was heard as if from a great

distance. After regaining his senses and control over his limbs, he estimated

that the time of paralysis lasted for only a minute. He descended to an altitude

of 50 m to find an appropriate landing spot until he felt that he could no

longer fly the aircraft. Afterwards he could not remember where he had landed.

He left the plane and collapsed." His memory of his transportation to the

hospital was blurred. Upon arrival von Richthofen immediately told his physician

that he had only been able to retain control of the aircraft because he had had

the firm conviction that otherwise he would have been a dead man.

The initial diagnosis on reaching hospital was "machinegun (projectile)

ricocheting from head". The stay in hospital was uneventful after surgery to

ascertain that the bullet had not entered the brain.

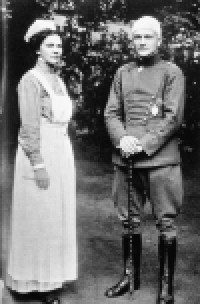

Figure 2: July 1917, von Richthofen with his nurse Sister Käte

at field hospital No 76 in Kortrik, Belgium, after having received a head

wound during aerial combat

Von Richthofen stayed in the field hospital for 20 days until July 25, 1917

(figure 2). He left because he wanted to take command of his wing again. The

skull wound was not closed, and the bare bone was probably visible until his

death. He was advised not to fly until the wound in his head had healed

completely. There is a special mention of the fact that even the surgeon in

charge held this opinion in the medical file. It was also recorded that "without

a doubt there had been a severe concussion of the brain and even more probable a

cerebral haemorrhage. For this reason sudden changes in air pressure during

flight might lead to disturbances of his consciousness". The record ends with

the statement that von Richthofen promised not to resume flying before he had

been given permission by a physician.

In the sky again

Kunigunde von Richthofen, mother of the Red Baron, recorded no unusual signs

of depression or self doubt when her son was on vacation at home in June, 1917.7

Von Richthofen returned to flying duty on August 18, 1917, and was credited with

his 58th aerial victory the same day.8 He was almost sick during this

first flight after the injury, and on August 27, 1917, another piece of bone was

removed from the open wound that still had a size of 2·5×2·5 cm.3

A new chapter of The Red Air Fighter was added in the spring of 1918,

in which von Richthofen mentioned his depression and melancholy when he thought

about the future. He describes a totally different von Richthofen than the one

who wrote the first edition of The Red Air Fighter. He feels unwell after

each air combat and attributes this feeling to his head injury. After landing he

stays in his quarters and does not want to see or to talk to anybody.

He also mentions the fact that he had been offered a desk job by "highest

order".9 Von Richthofen's biographer Rolf Italiaander also mentions

this incident and emphasises that the Kaiser himself had expressed this wish.

Oberleutnant Bodenschatz makes no mention of it in his wing diary8

even though, according to Italiaander,10 he gave the message from the

Kaiser to von Richthofen. An inquiry at the archives of the former ruling house

of Prussia did not turn up such a written order. Von Richthofen refused to leave

his wing. It is interesting to note that more than 50 years later during the

Cold War Yuri Gagarin and John Glenn were denied a second spaceflight by their

countries' leaders because they were heroes whose lives should not be risked.

At the end of January, 1918, when on another visit home, his mother noted the

change in her son: she describes him as taciturn, distant, and almost

unapproachable. She thought that he had changed because he had seen death too

many times.

Fitness for flying duty

Since there were no special rules concerning fitness to fly a combat

aircraft, a general view of the ability to perform combat duty has to be

considered to determine von Richthofen's ability to serve after his head injury.

In the general rules for determining fitness for military duty that were drawn

up in peacetime, a head injury or malformation made a person ineligible for duty

only if he could not wear appropriate headgear such as a helmet or cap.6

Pictures of von Richthofen during parades show him wearing a cap with his

dressed head wound, so the rule did not apply in his case. Taking a more serious

look at suitability for duty of wounded soldiers was necessary after the war

dragged on and new replacements became scarce. A series of medical conferences

was held in the autumn of 1916 sponsored by the Prussian Ministry of War

concerning the evaluation of fitness for military and combat duty of soldiers

who had received injuries or wounds. Kurt Goldstein (professor of neurology from

Frankfurt am Main) gave a lecture on brain injuries and concluded that fitness

for combat duty would only be restored in rare cases and that a qualified

evaluation of the course of disease was necessary to make such a determination.

He pointed out that only 20% of patients with a skull wound and only 4% of those

with a brain injury wound were deemed fit for combat duty again.11

According to those recommendations, von Richthofen should not have been allowed

to return to active flight duty since he was diagnosed as having a concussion

and cerebral haemorrhage. The physicians and surgeons who treated him knew this,

as can be concluded from their strong recommendation to von Richthofen not to

fly before his head wound had completely healed.

Killed

in action

On April 21, 1918, von Richthofen was shot dead while on a patrol flight. He

died just 2 weeks short of his 26th birthday. He was the most successful ace of

World War I, and credited with 80 aerial victories. Many attempts have been made

to answer the question of whether he was killed by a bullet from the air or

ground. Some historians believe that he was shot down from the air by Captain

Roy Brown, a Canadian serving in the Royal Air Force, although a hit from the

ground cannot be ruled out. On the evening of April 21, 1918, an inspection of

the body by a Captain and a Lieutenant of the British Royal Army Medical Corps

showed an entrance wound on the right side of the chest in the posterior fold of

the armpit; the exit wound was situated at a slightly higher level nearer the

front of his chest, about half an inch below the left nipple and about

three-quarters of an inch external to it. On April 22, 1918, the consulting

surgeon and the consulting physician of the British 4th Army made a surface

examination of the body. They found the wounds as described above "and also some

minor bruises of the head [and] face. The body was not opened--these facts were

ascertained by probing from the surface wounds". Thus ends the available medical

record for the Red Baron.

Conclusion

After reviewing the available medical information on von Richthofen and the

state of the art in neurology and psychiatry at the time, it is probable that the Red

Baron should not have been declared fit for duty after the head wound he

received on July 6, 1917. It is most probable that after having been released

from the field hospital under the instruction to fly only after getting

permission from a physician there were no further medical checks.

The times were such that manpower was sparse. An experienced ace and hero

such as von Richthofen could not be grounded against his wishes for public

relations reasons. Furthermore von Richthofen's sense of duty and comradeship

would not have allowed him to desert his fellow soldiers while he still felt

capable of aerial combat.

Epilogue

It was not until 1975 that von Richthofen's remains found a (hopefully final)

resting place. After his death he was first buried in a village churchyard at

Bertangles near Amiens, France, with full military honours by the Commonwealth

forces. Later the coffin was transferred to a War Graves Commission cemetery.

During the Weimar Republic, the Invalidenfriedhof in Berlin--the Prussian

equivalent of the US Arlington National Cemetery--was to become his resting

place by wish of the German government and veterans' organisations. On Nov 20,

1925, he was reburied there. The German President Paul von Hindenburg as well as

the Chancellor with nearly the whole cabinet were among the dignitaries present.

Von Richthofen's reburial was seen as a symbol of homecoming that was

appreciated by the many people whose loved ones were buried in foreign soil or

missing in action.

In 1961 when the Berlin Wall was constructed, the Invalidenfriedhof was at

the very edge of the demarcation zone in the Russian sector. It was only

possible to visit the cemetery with special permission. For this reason von

Richthofen's surviving brother, Bolko, who had been in charge of the transfer of

the remains from France in 1925, got permission from the East German government

to rebury the remains in the family burial plot in Wiesbaden before his death in

1971. The reburial book place in 1975. The original grave marker is kept by the

Jadgeschwader Richthofen in Wittmund, Ostfriesland.

|