|

The Aces of WW1

Roland Garros

and the air Aces

At the opening of the war, France held the lead in the air

with the most aircraft and the most

experienced pilots.

Aircraft were used mainly for reconnaissance, but in the

early days of 1914 aerial

reconnaissance reports (such as

those detailing the German advance through Belgium as

General von Moltke outflanked the French and British

armies) were ignored.

The Allies were just barely able

to recoup and, this time believing

aerial reports, halted the German

advance at the Maine River, along

which both sides dug in for a long

standoff. At first, spotters who

rode as passengers waved to

enemy aircraft; soon they used pistols and rifles to

try and shoot down

their adversaries. This was totally ineffective given

all the buffeting and vibrations the spotter

would experience even in a smooth flight. (The rotary

Gnome engines were highly efficient and

reliable, but the fact that

the entire engine rotated with the propeller

meant the aircraft

experienced a great deal of vibration.)

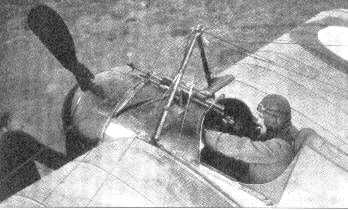

The solution was thought to be machine guns. The

French Hotchkiss, the

Belgian Lewis, the British Vickers,

and the German Spandau and Parabellum

were all well-crafted

weapons that allowed gunners to spray the enemy

with a barrage of fire,

increasing the chance of a hit. But

this was a very limited solution, first, because the

gunner was

at the mercy of the pilot’s sudden manoeuvring, and

second, because a very important target

area right in front of the

plane was eliminated from the gunner’s field

of fire.

By 1915 Curtiss Jenny Trainers were

outfitted with synchronized machine guns,

but they were not as reliable as Fokker planes.

The

Morane-Saulnier Type N planes were equipped with

deflector plates

The British were

already advanced in machine gun

technology thanks to Maxim. Eventually, the Lewis gun

gave airplane gunners lethal range and

flexibility.

Some work had been done before the

war in developing a mechanism that

would allow the pilot to aim a

machine gun through the whirling

blade of a propeller without destroying it, but it had

proven unreliable. The

solution to the problem came about as a result of

a collaboration between the French aircraft

designer-builder Raymond Saulnier of the

Morane-Saulnier firm and the

world-famous aviator Roland Garros,

who had been the first to fly solo across the Mediterranean

in 1913, using a

Morane-Saulnier Parasol.

These two men developed a

deflector shield for the propeller

blade that would deflect rounds.

Garros tested the device on a

Parasol airplane against four

German fighters on April 1, 1915.

The German fliers were stunned by Garros’ ability

to simply aim his aircraft

and fire in a direct line to wherever he was pointing. An

added feature incorporated the

firing mechanism onto the joystick, giving the pilot

easy control of both the flight

and the shooting. On April 19,

Garros’ plane was forced down behind enemy lines and

he was captured before he

could destroy it. The Germans were

now in possession of the secret, but

there was no need to copy

it, thanks to a capable airplane builder and

entrepreneur named Anthony Fokker, with a lethal secret of

his own.

The first “aces” (an unofficial title

given to fighter pilots who had shot down five enemy

aircraft) were Garros and Adolphe Pegoud, the aerobatic

pilot who had demonstrated loops and dives before the war.

Garros escaped in 1918 and returned to service, only to be

shot down and killed later that year. Pegoud died on August

15, 1918, while on a reconnaissance mission.

The only German aviator in the early

stages of the war was Ernst Udet, later to become the second

highest rated German ace. Udet began the war in an Aviatik

B, used mainly for spotting, and then flew the faster “D”

planes built by Siemens-Schuckert. (Udet committed suicide

in 1941 rather than continue as a spokesman for the

Luftwaffe.)

The only British aviator to emerge at

this stage was Lanoe Hawker, winner of the Victoria Cross

for defeating three German aircraft from his Bristol Scout.

Hawker was to become an important architect of Allied air

power, but at this stage there was little a plane could do

other than bombing and bringing down the air-ships

(“sausages”) the Germans used to guide artillery fire, and a

plane could do this only while heavily protected by

ground-based anti-aircraft fire (“Archie”) and by fiery

artillery shells (“flaming onions”).

The aces rapidly assumed

important roles in strengthening public morale and

bolstering support for the war effort. Their images sold war

bonds, and they visited factories and schools. They were the

subject of newspaper and magazine articles. Some published

best-selling autobiographies, such as Baron Manfred von

Richthofen’s The Red Battle Flier in 1917 and Oswald

Boelke’s Hautpmann Boelckes Feldberichte published in 1916.

Other pilots who died in combat, such as Max Immelmann, had

their collections of letters published. The ace symbolized

everything people thought a warrior should be. They followed

the moral code of war which many felt had been forgotten in

the trench war by the land troops. In some ways this was

true. Flyers respected each other’s abilities, even if they

were the enemy, because each knew the difficulties and

dangers that others faced in the sky.

In no country was this

public role more important than in Germany. Before the war,

the government had worked hard to promote the zeppelin as

the aerial weapon of the German people, successfully gaining

massive public support. But as the war progressed, the

airplane proved to be a more effective weapon, and the

government needed to shift popular support away from the

zeppelin. For this they used the aces, promoting them as

modern knights—brave, daring, and chivalrous--who embodied

all that was best about the German warrior. The nation’s

highest military honour, the Pour le Merite, was given to

aces. They dined with princes. Children collected trading

cards with their images. When Oswald Boelke died, he was

given a funeral worthy of royalty. The German public loved

the aces and threw their support behind the airplane.

In keeping with their image

of modern knights, many of the public believed that aces

would stop firing when his opponent ran out of ammunition or

in some way could not fire back. But pilots said they rarely

did this. In fact, in his autobiography, German ace Manfred

von Richthofen (the "Red Baron") said he once made the

mistake of allowing a pilot with a jammed machine gun to

land in order to be captured instead of killed. When von

Richthofen landed beside the plane, the downed pilot

suddenly opened fire on him. Having been tricked once, von

Richthofen decided never to be gullible again and always

fought until the plane had crashed with a dead pilot.

Manfred von Richthofen was the most famous ace of the war.

Aces almost always preyed

on two-seat reconnaissance planes or anyone else who was

unlikely to defeat them. The picture of two knights jousting

often depicted in stories of the aces, even on book covers

and recruiting posters, was largely fictional. German

doctrine said to attack only when there was an advantage.

The aces who survived were always careful and never

reckless. Thus, battles between two aces were rare, and even

in those unusual cases where two pilots engaged each other

in battle, the airplanes or machine guns involved were

rarely equal.

The possibility of earning

the title of ace was a strong incentive for these

competitive and proud pilots to risk their lives repeatedly,

spurring many through their first months of combat. Once

they had become aces, the lure of medals and prestige

continued to drive them. When compared to other military

groups, combat pilots won a disproportionate number of

military medals. Also, solo pilots, away from the eyes of a

commanding officer or co-pilot, could engage the enemy

without the threat of court martial or other punishment.

"Mick" Mannock of

Great Britain routinely shared victories with other pilots

or didn't bother submitting claims for enemy aircraft he'd

shot down in combat. After selflessly sharing his 61st

victory with Donald Inglis, a newcomer from New Zealand who

had yet to score, Mannock was killed when his aircraft was

shot down in flames by machine gun fire from the ground.

Inglis was also brought down by ground fire but survived.

The downside was that many

pilots took extreme risks. Of the 20 highest scoring aces,

12 were killed in action. (Incidentally, the top five

American aces, led by Eddie Rickenbacker with 26 victories,

survived the war.) The higher ranked an ace was, the more

often he had placed himself in extreme danger to achieve his

military goals, and the greater the probability that he

would die fighting. For many pilots, death was the only way

to stop their climb in the rankings.

Rene Fonck was the

highest scoring ace for France and the Allies.

For many World War I

aviators, however, death arrived not through the enemy but

through the equipment that took them into battle. It was

said that the Sopwith Camel killed more British pilots than

the enemy did because of the airplane’s handling problems.

The Fokker DR.V’s top wing had a tendency to peel off in

flight. These dangerous airplanes, plus the lack of pilot

experience and the absence of parachutes, made a deadly

combination.

Georges Guynemer was France's most popular ace.

Whatever the realities, the

aces became the heroes of the war. And they have passed into

the pages of modern mythology. They presented a vision of

war based on past virtues like chivalry and decorum. But

they were also modern-day heroes: they flew machines instead

of riding horses, and many were from the middle class, not

the aristocracy. This new age meant men such as Georges

Guynemer, a weak, sickly son of an insurance salesman, could

become a national hero and be memorialized in the Pantheon

with other French heroes like Voltaire, Victor Hugo, and

Marie Curie. And in his death, Guynemer reached an

unsurpassed level of mythology--his airplane simply

disappeared during a dogfight in September 1917. Neither the

airplane nor Guynemer was ever found. In the minds of the

French, their great hero simply flew into the heavens, like

a Greek god.

aces

with more than 40 kills

|

Kills |

Ace |

Nation |

|

80 |

Manfred von Richthofen |

Germany |

|

75 |

Rene

Fonck |

France |

|

73 |

Edward

Mannock |

Great

Britain (Ireland) |

|

72 |

William Bishop |

Great

Britain (Canada) |

|

62 |

Ernst

Udet |

Germany |

|

60 |

Raymond Collishaw |

Great

Britain (Canada) |

|

57 |

James

McCudden |

Great

Britain |

|

54 |

A.

Beauchamp-Proctor |

Great

Britain (South Africa) |

|

54 |

Donald

MacLaren |

Great

Britain (Canada) |

|

54 |

Georges Guynemer |

France |

|

53 |

William Barker |

Great

Britain (Canada) |

|

53 |

Erich

Loewenhardt |

Germany |

|

48 |

Werner

Voss |

Germany |

|

47 |

Raymond Little |

Great

Britain (Australia) |

|

46 |

Philip

Fullard |

Great

Britain |

|

46 |

George

McElroy |

Great

Britain (Ireland) |

|

45 |

Charles Nungesser |

France |

|

45 |

Fritz

Rumey |

Germany |

|

44 |

Albert

Ball |

Great

Britain |

|

44 |

J.

Gilmore |

Great

Britain |

|

44 |

Rudolf

Berthold |

Germany |

|

43 |

Paul

Baeumer |

Germany |

|

41 |

T.

Hazell |

Great

Britain (Ireland) |

|

41 |

Joseph

Jacobs |

Germany |

|

41 |

Bruno

Loerzer |

Germany |

|

41 |

Georges Madon |

France |

|

40 |

Oswald

Boelcke |

Germany |

|

40 |

Franz

Buechner |

Germany |

|

40 |

Lothar

von Richthofen |

Germany |

|

40 |

Godwin

Brumowski |

Austria-Hungary |

|

40 |

Ira

Jones |

Great

Britain |

|