|

the airships

The dream of floating fortresses that could rain

devastation on the enemy was tested in World War One. The reality proved

to be very different. The German Air Command's plan for the conquest of

Britain failed to achieve it's intended goal. The promise of the Airship's

potential was an empty one

|

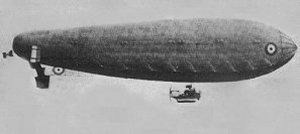

Photograph of a German Zeppelin taken in 1916. |

Italian Dirigible tipo M was powered by Fiat S76 A Engine. |

Italian Forlanini Airship powered by Isotta Fraschini V5 Engine .

The First Zeppelin

Kill

Zeppelin LZ 37

Country: Germany

Length: 521 feet

Volume: 935,000 cubic feet

Lifting Gas: hydrogen

Armament: four machine guns

On

June 17, 1915, Lt. R.A.J. Warneford of the RNAF was flying toward Ostend.

I was his first night flight, and he was going to bomb theZeppelin sheds

at Evere. He spotted a large cigar-shaped object in the clouds. As he drew

nearer he saw that it was the German Zeppelin LZ 37.

Warneford's Morane Saulnier L only carried a few bombs

and a carbine. The Zeppelin continued to fire at him as it's crew dumped

ballast. The LZ 37 rose rapidly higher into the sky. Warneford struggled

to gain altitude. Warneford pursued the Zeppelin into the early morning.

Suddenly the Zeppelin nosed down and began to lose

altitude. Warneford pushed his plane until he was over the zeppelin and

released his bombs. After a few moments, there was a tremendous explosion,

and the Zeppelin LZ 37 fell to the earth engulfed in flames. Lt. Warneford

was the first Allied flier to bring down a Zeppelin.

View from a German

Zeppelin

the birth of

strategic bombing

The Birth of Strategic Bombing was in WWI when German

Zeppelins began raiding London from bases in occupied Belgium. Small

attacks against England were carried out early in the war, but by October

1915, "squadron-size" raids by numerous Zeppelins had begun, always at

night and in the dark of the moon. Early in September 1916, a British

fighter shot down an airship, and three weeks later, two Zeppelins

attempting to attack London were also destroyed. Although Zeppelin

performance was gradually improved, so were British balloons, and improved

anti-aircraft defences and heavy losses continued. After a disastrous raid

on August 5, 1918, the Germans practically discontinued Zeppelin warfare.

There were 159 Zeppelin attacks against England in WWI, resulting in the

death of 557 people, primarily civilians, and damages of $7,500,000.

The L33

Raid: A game changer

June 21st, 2009

Raul Colon

Email:rcolonfrias@yahoo.com

During the afternoon of September 23rd 1916, one of the Ďnext generationí

super-Zeppelins, L33, took to the air for its first operational mission:

the bombing of downtown London. Just a few months before, L33 was on the

ground, getting its final fittings and adjustments. The L33 was truly a

remarkable piece of engineering. She was 649í long, with a 78 feet

diameter and with a total gas capacity of 1,949,000 cubic feet. Six

powerful Maybach 240hp Hslu engines gave the lumbering giant a top speed

of 59 mph at a maximum operational ceiling of 13,500 feet. Beside its

sheer size, what separated the L33 from its predecessor was its bomb load

capacity. An impressive five tons of ordinance could be carried.

On that fateful afternoon, L33 was accompanied by ten additional

super-Zeppelins of the Imperial German Navy. The mission called for the

eleven to reach the British coastline at the same time. After which, each

craft would take off to its pre-designed target area. Eight Zeppelins were

assigned to strike targets around the Wash. The remaining three units were

to hit the British capital. Taking part in the London raid was L31 under

the command of Heinrich Mathy, L32, lead by the enigmatic Werner Peterson

and the L33, controlled by Alois Bocker.

L33, which departed Nordholz, was fitted with almost three tons of free

fall bombs. At approximately ten oíclock GMT, L33 flew over Britainís

coast. The huge dirigible was spotted by some local boys near Thames

Estuary. From the Estuary, it moved on towards the north east in order to

avoid the heavy saturated British defences in the east. At the same time,

L31 and L32 were crossing the coast heading towards Dungeness, a path

seldom explored by German and British planners.

At 11:48 pm, Bocker ordered L33ís bombs to be dropped. Six high explosive

bombs landed on Hornchurch. Twenty minutes later, the L33 was seen passing

West Ham by a couple of street policemen. They promptly alerted the

authorities. Searchlights blanketed the pass between Ham and London. After

five intensive minutes of searching, no Zeppelin was spotted, thus, the

search was called off, for the time being.

A little over 12:05 in the morning, Londonís powerful searchlights were

turned on. The spotters must have seen the sight of the German slow

moving dirigible, because an intense ground attack commenced short after.

Bockerís airship was cruising at 12,000 feet following the Hamís banks

when fire erupted. Despite it all, he and his crew kept up L33ís attack

all the way up to Bromley-by-Bow, where the gas giant dropped its main

ordinance. One 100kg bomb and five small, incendiary bomblets landed on

St. Leonardís and Empress Streets.

Four urban houses were damaged and six people were killed on this early

stage of the raid. L33 went on to deliver several more bombs in and around

Bow. But by this time, the airship was shadowed by British defences. Low

trajectory shells began to find its mark. Several fragments of high

detonation shells exploded only a few feet away from the shipís skin

puncturing one gas cell. Now the big air platform was in trouble. It began

losing altitude fast. At 12:20 am, L33 was seen crossing Buckhurts Hill,

leaking gas. Besieged by heavy ground fire, and declining altitude, Bocker

decided to dump water from the shipís ballast tanks, which caused the L33

to regain some of the height it had lost but the damage was done.

Near Kelvedon Common, a new and more ominous threat arrived: a British

pursuit airplane. Second Lieutenant Alfred de Bathe Brandon was ready for

the opportunity to engage the German ship. He had gained valuable

experience in March 1916, when he almost single-handedly severely damaged

L15. Brandon met L33 head on, emptying his Lewis gun, fifty explosive

incendiary bullets, into the airshipís stern section. He swung around and

hit the stern again, but his gun jammed forcing him to call off the

engagement. L33 escaped, at least for the moment.

It was now 12:45 and the dirigible was passing by Chelmsford, still losing

precious high. In an attempt to stem the descent, all non-essential

materials aboard were jettisoned. Twenty five minutes after, at 1:10,

Bockerís ship passed over the Essex coastal area near Mersea Island. Its

destination was the security of the Belgium skies. Unfortunately for

Bocker and his crew, L33 was doomed. The Zeppelin was almost out of gas,

losing altitude fast and its structure was compromised. It would go down

and the only question for Bocker was where.

A crash landing at sea, at that hour, was deemed too risky. Better off,

the commander thought, made a semi-controlled decent in British territory,

then deal with the imprisonment issue. Immediately, the ship began to

turnaround, now headed back to Essex. She managed to return to the coast.

Two and a half miles inland, at 1:20am, L33 went down on a desert field

near Peldon and Little Wigboroug church. The crew managed to escape before

the gas giant was engulfed in a fire storm.

Soon after the fire died down, and with the metal frame still standing,

Bocker ordered his men to climb back into what was left of the

super-Zeppelin to destroy any classified material. Despite their best

efforts, the British still were able to gather many essential documents

and systems out of the wreck. Data that would be later incorporated on the

R33 platform.

When the crew saw the first police cars arriving on the field, they

promptly left the area. But the trip back to the coast was short lived.

Specialist, Edgar Nicholas, apprehended the entire crew without even

firing a shot.

The crew of L33 was questioned extensively by British military and

scientific personnel. Even psychologists were brought in to exanimate the

men mental profile. Such was the depth of the debriefing phase. As for the

dirigibleís debris, they were studied by engineers for days. After

authorities were satisfied that every drop of information was collected,

the shipís frame was burned to the ground.

In the final analysis, the end of L33 did not alter the rate of Zeppelin

attacks, but what it did was to enforce a view held by many German

commanders, Zeppelins alone would not defeat Great Britain. A new weapon

was needed. One year later, that weapon would make its present felt.

World War I, HP Willmott, Covent Gardens Books 2003

The First World War, Hew Strachan, Penguin Books 2003

The Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft, Robert Jackson, Parragon Publishing

Book 2002

|