Boeing B-52D. A 99th Bomb

Wing Boeing B-52D enroute to Hanoi during Operation Linebacker II in

December 1972.

In his 1832 book On War,

Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz described war as "continuation of

politics by other means." Nowhere was this better illustrated than in the

December 1972 bombing raids, dubbed "Linebacker II," on Hanoi in North

Vietnam. They were ordered by President Richard Nixon in response to North

Vietnamís exit from peace talks in Paris. Seeing popular and congressional

support for the war dwindling, Nixon had hoped that the talks would yield

a peace settlement by the end of the year and that the United States could

leave Vietnam gracefully. He had to show North Vietnam he would not stand

for a delay in negotiations. But Nixon also had to assure the South

Vietnamese that the U.S. commitment to them would continue after the

departure of American troops. And this had to be done before Congress

reconvened in January, when it was certain to cut off funds for the war,

effectively ending it. Consequently, Nixon ordered three days of bomber

strikes on North Vietnamís cities, which would be extended if Hanoi still

did not return to the talks.

Because December is monsoon

season in Southeast Asia, the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, with its

all-weather bombing capacity, was chosen as the primary aircraft for the

campaign. Further, the B-52 was a cornerstone of Americaís nuclear

delivery triad, which also made it a particularly valuable weapon.

Bringing in massive numbers of this weapon was a signal that the United

States was serious about returning to the negotiating table. And it also

showed that the United States had the strength, power, and stable of

weapons needed to continue the war indefinitely. According to national

security advisor Henry Kissinger, it was the B-52ís "ability to shake the

mind and undermine the spirit" that made it the most desirable weapon for

the operation.

Operating from Andersen AFB, Guam

and later U-Tapao Royal Thai Air Base, the B-52 was a major component of

many operations including Linebacker and Linebacker II.

But Nixon was playing a

risky game. The psychological boost to North Vietnam that could result

from downing a B-52 could encourage it to continue to fight. If too many

of the planes that were presented as Americaís greatest were shot down,

the United States would appear weak, an especially bad image to portray

during the Cold War. Just as the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

symbolized Americaís nuclear might to the Soviet Union, Linebacker II was

to impress the Communist nations with Americaís strength.

The first day of Linebacker

II was December 18, 1972, five days after the Paris peace talks broke

down. At 2:41 p.m., 129 B-52s took off in three waves from Anderson Air

Force Base in Guam. The waves were made up of cells--groups of three B-52s

that flew together for electronic countermeasure (ECM) integrity and

targeting purposes. They had a large escort: the 7th Air Force and U.S.

Navy: KC-135 refuelling planes, F-4 fighter escorts, F-105 Wild Weasels

(to attack surface-to-air missile, or SAM, sites), Navy EA-6 and EB-66

radar-jamming planes, search and rescue teams, and F-4 chaff planes.

(Chaff planes are planes that release "chaff," strips of metal that are

dropped to confuse radar.)

On the first night, three

B-52s were shot down. But 94 percent of the bombs were released over their

targets. Because of the operationís size and the lengthy flights, the last

planes from Day One were landing back at Guam as the first planes for Day

Two were taking off. Crew debriefings were analyzed as quickly as possible

but not quickly enough to incorporate changes for the second dayís plans.

So Day Two proceeded along the same lines as Day One. Targets included

rail yards, power plants, and storage areas. And because of the low number

of casualties on Day Two, operations for Day Three continued in the same

way. This was to prove a fatal mistake.

The American crews were

learning the pattern, and were becoming complacent. Unfortunately, the

North Vietnamese were also learning the pattern. On the third day, the

waves of B-52s approaching Hanoi saw North Vietnamís MiGs in the distance.

But rather than attack, the MiGs reported the Americansí heading,

altitude, and air speed to ground forces. Heavy SAM activity and

anti-aircraft artillery firing directly into the planesí paths resulted in

the deadliest day of the operation: six B-52s were shot down. With the

loss of the $8-million bombers leading to congressional and public anger

and calls to end the bombings, it began to look as though Hanoi might be

able to hold off peace negotiations until Congress returned in January.

Nixon, however, still extended the three-day action to an operation of

"indefinite" length. Military planners had to find a way to succeed.

And there were many

problems to fix. The bomber waves were each 70 miles (113 kilometres)

long. Nicknamed the "elephant walk," the long line was slow, predictable,

and an easy target. The "chaff corridor" showed where the bombers would be

headed. It was like the "Yellow Brick Road" for SAM operators. And after

dropping their bombs, the B-52s left their targets in a steep 180-degree

turn that made a large, bright flash on the enemyís radar screens.

Although bomber cells date

from World War II, they became essential to survival with electronic

warfare. B-52sí ECM worked only when the cell remained together and

retained their integrity. Commanders threatened court-martials for anyone

who knowingly compromised cell integrity. This tough measure proved

justified when two planes, lost on Day Three, had been without full ECM

capabilities because they were missing the third plane in their cells

(they had aborted for technical reasons). Evasive manoeuvres, the best way

to avoid SAMs but also a destruction of cell integrity, were forbidden.

Evasive manoeuvres also

threatened to cause bombing mistakes, leading to civilian casualties. Bomb

targeting needed bombs to be released at a certain altitude and location.

If any components were changed, the bomb would be off target and might

land on civilians. Radar navigators were also ordered to bring their bombs

back if they were less than 100 percent sure they were on target, and all

maps showed schools, hospitals and prisoner-of-war camps clearly marked.

The F-111A in this photo is on

display at the U.S. Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio. It is marked as it

was in 1972-73 when assigned to the 474th Tactical Fighter Wing during

Linebacker II operations in Southeast Asia.

In light of the 20,000 tons

of bombs that were dropped on the citizens of Hanoi and Haiphong, there

were relatively few casualties. Only 1,318 people were killed in Hanoi and

306 in Haiphong, a truly remarkable number. By comparison, during nine

days of bombing on Hamburg, Germany, in 1944, less than 10,000 tons were

dropped and 30,000 people died.

North Vietnam spent the

36-hour Christmas stand down restocking their SAM arsenals. They hoped

that if they shot down enough bombers and could hold strong until January,

the U.S. Congress would reconvene and legislate the end of the war. U.S.

Air Force planners spent the holiday completing plans for the next phase

of the operation--the targets were airfields and SAM storage and assembly

sites. By knocking out the air defences, B-52 losses would be reduced. And

the United States would have freedom of the skies, able to attack at will.

December 26, 1972, was the

day the new tactics were put into action. Crews were now allowed to take

evasive manoeuvres against SAMs except during the bomb run itself. The

sharp post-target turns were changed to long, shallow ones. And most

importantly, in place of the elephant walk, crews were given multiple

flight paths they could follow to the targets that would still get them

there at roughly the same time. The corridors of chaff became clouds--the

chaff was dropped in large formations around the target, which were less

likely to lead the enemy to the bombers.

Day Eight was a

success--Hanoi blinked and contacted Washington about resuming talks. But

Nixon would not call off the bombings until talks had actually resumed.

The final two days of Linebacker II encountered only one problem: a lack

of suitable targets. Linebacker ended on December 30. On January 23, 1973,

the cease-fire was signed, to take effect four days later.

Many in the air force

erroneously believed that if they had been allowed to run a similar

bombing mission in 1965, the war would have ended sooner. They failed to

recognize that in 1972, the war was winding to an end and the bombing was

only the final push. Also, U.S. relations with China and the Soviet Union

had changed in the intervening years, and bombing in 1965 would have

encouraged them to join the fight, which perhaps would have escalated into

a nuclear conflict. The terms of peace had also changed as the United

States went from wanting victory to settling for an easy exit. The success

of Linebacker II was part tactic, but mostly timing.

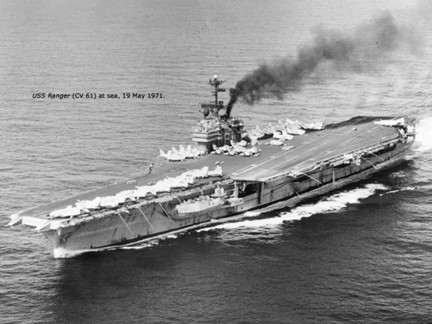

The USS Ranger, shown in

this photo, was one of the carriers participating in Linebacker II. The

others were the USS Enterprise, USS Saratoga, USS Oriskany, and USS

America.