On March 24, United States military forces, acting with their NATO allies, commenced air strikes against Serbian military targets in the Former Yugoslavia. About 7,300 U.S. Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps service members were assigned to the United States European Command in support of the operation. The multinational force was tasked by NATO to bring a swift end to hostilities committed by the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia against ethnic Albanians in the southern province of Kosovo.

This operation, codenamed Allied Force by the United States and Determined Force by NATO sought to:

-

Deter further Serbian attacks against the people of Kosovo

-

Reduce the ability of the Serbian military forces to continue their offensive operations against the people of Kosovo

-

Degrade Serbian air defence systems in order to reduce the risk and threat to NATO aircraft and crews

On 09 October 1998 the US committed Operation Cobalt Flash forces to support the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Operation Determined Force in possible air raids against Serb forces in Kosovo. These forces began operations against Serbia on 24 March 1999, as part of Operation ALLIED FORCE, as the campaign was renamed upon execution.

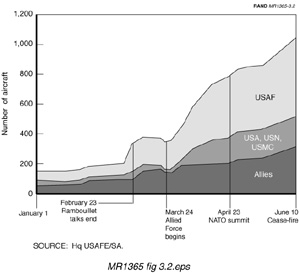

Although initially no forces moved into place, the US commitment involved more than 200 aircraft, including a Navy carrier air wing. President Clinton approved Secretary of Defence William S. Cohen's recommendation to commit the "substantial forces" to stand ready as diplomats from the United States and other nations make final attempts to resolve the conflict in the Balkans. While the force commitment did not signify that a NATO political decision to use military force has been taken, it did signal the commitment of the U.S. government to the resolution of the crisis in Kosovo.

The US commitment of about 260 aircraft would support NATO air operations. Overall, NATO plans for 430 aircraft, bringing the U.S. force to about 60 percent of that total. As of early October 1998 the US commitment included:

-

About 120 land-based multirole aircraft, including F-15s, F-16s, F-117s and EA-6B's;

-

A Navy carrier air wing of 72 aircraft, including 46 strike and 26 support aircraft;

-

Six B-52 and two B-2 aircraft;

-

About 10 reconnaissance aircraft;

-

About 10 search-and-rescue aircraft;

-

Three airborne command-and-control aircraft;

-

About 40 refuellers; and

-

Navy surface combatants of the Sixth Fleet.

The US Air Force formed four air expeditionary wings on 11 Oct 1998 to help simplify lines of command and control should a NATO-led force be directed on Kosovo and NATO call for an air strike on Kosovo later that week. The units were formed to support the possibility of air operations over Serbia. The activation of an expeditionary command and control structure, under the leadership of Air Force Lt. Gen. Mike Short, 16th Air Force commander, signalled a transition from military planning to military operations.

-

16th AEW with B-52 bombers capable of delivering conventionally armed cruise missiles, RC-135 reconnaissance aircraft, F-15C multi-role fighters and KC-135s

-

31st AEW-SA includes F-16C/CG multi-role fighters, A-10 ground attack aircraft, EC-130 airborne battlefield command and control centres, U-2 reconnaissance aircraft and KC-135s. Deployed at Aviano Air Base, Italy, the 31st Air Expeditionary Wing also includes U.S. F-117s, F-16s, O/A-10s, EA-6Bs, EC-130E, EC-130Hs, and KC-135s; Portuguese EF-18s; Canadian CF-18s; and Spanish KC-130s, supporting both Bosnia and Kosovo operations.

-

86th AEW-SA includes C-130 airlift aircraft and KC-10 air refuellers

-

100th Expeditionary Air Refuelling Wing includes KC-135 Stratotankers.

The four new AEWs joined three Air Force wings already in Italy supporting air operations in Bosnia. About 65 Air Force aircraft are involved with this operation.

bomb damage in Belgrade

Approximately 15 F-15C Eagle fighter aircraft and approximately 250 airmen from the 48th Fighter Wing [the "Liberty Wing"] deployed from RAF Lakenheath to a forward location at Cervia AB Italy in support of possible NATO contingency operations in Kosovo. Six B-52 Stratofortress aircraft arrived at RAF Fairford on 11 October 1998 from Barksdale Air Force Base LA to support possible NATO contingency operations in Kosovo. About 260 US airmen also deployed to support the B-52s. Fairford was selected to receive the aircraft because of its runway length and ability to be activated at short notice at any given time. Fairford is a former Strategic Air Command base and is still used as an alternate emergency landing site for the space shuttle.

The first phase of this multinational operation was initiated on October 13th 1998. That day, NATO's higher decision-making body - the North Atlantic Council - authorised an activation order allowing for both "limited air strikes" and a "phased air campaign" in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia should Yugoslav authorities refuse to comply with the UN resolution. The execution of these air strike options was initially set to begin not earlier than 96 hours from the authorization of the activation order, to allow time for negotiations between Ambassador Holbrooke and FRY President Milosevic to bear fruit.

On October 14, 1998, due to persisting tension in Kosovo, NATO's Standing Naval Force Mediterranean (STANAVFORMED) is temporarily detached to the Adriatic.

Progress in the diplomatic negotiations was largely due to pressure maintained by the Alliance maintained through deployment of NATO air and naval assets in Italy and in the Adriatic sea. After nine days of negotiations, Ambassador Holbrooke secured an agreement from Mr. Milosevic to comply with the provisions of UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1199, with both air and ground regimes to verify compliance.

In accordance with this agreement, signed on October 15th, Mr. Milosevic committed to cease hostilities and withdraw mobilized forces in Kosovo. Furthermore, the agreement allows the international community to verify compliance by all parties with the provisions of UNSC Resolution 1199. This is to be conducted through NATO unarmed flights and the deployment in Kosovo of a Verification Mission provided by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

President Milosevic

On October 16, 1998 the Chairman-in-Office of the OSCE and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) sign in Belgrade an agreement establishing a verification mission in Kosovo, including the undertaking of FRY to comply with UNSC resolutions 1160 and 1199 of 1998. And on October 24, 1998 the UN Security Council adopts Resolution 1203. The resolution supports NATO and OSCE verification missions and demanded that all parties in Kosovo comply with the agreement.

As the 96 hour deadline for compliance with the negotiated settlement approached, the international community had clear evidence that Yugoslavia was still some distance from full compliance with the terms of the accord. While diplomatic efforts continued to secure full compliance, NATO decided to extend the period before execution of air strikes would begin. The extension gave Mr. Milosevic until 27 October 98 to comply fully with UNSCR 1199. NATO additionally decided to maintain its readiness to launch air operations against the FRY, to include continuing deployment of substantial air forces in the region.

Just prior to the end of this extension on 27 October, evidence indicated that Serbian military and security forces had made progress toward the demanded restraint and withdrawal. Despite the substantial steps, NATO's objective remained to achieve full compliance with UNSC resolutions. As a result, NATO decided to maintain both activation orders in place, with execution subject to decision by the North Atlantic Council. On October 25-26, 1998 NATO's Supreme Allied Commander Europe and the Chairman of NATO Military Committee meet with Yugoslav President Milosevic and his Army Chief of Staff. NATO delivers a clear message pressing for immediate and total compliance with Security Council Resolution 1199 and related agreements. On October 27, 1998 NATO decided to maintain the ACTORD and to remain prepared to carry out air operations should they be necessary.

Belgrade under bombardment

Despite the progress made, the crisis was not over. NATO remained ready to act. The North Atlantic Council kept the situation in Kosovo under constant review. The ACTORDS for limited air operations and for phased air campaign remained in effect. NATO military forces remained prepared to carry out air operations should they be necessary.

Meanwhile, NATO's focus was on ensuring the effectiveness of the verification regime with Operation Eagle Eye.

On January 20, 1999 NATO decided to increase the readiness of the assigned forces so as to make them able to execute the operation within 48 hours. And on January 29, 1999 NATO decided to further increase its military preparedness to ensure that all demands by the international community are met. On January 30, 1999 the Contact Group demanded all parties to agree on a political settlement for Kosovo by 20 February 99. NAC agreed that NATO's Secretary General may authorise air strikes against targets on FRY territory.

On February 19, 1999 NATO's Secretary General reaffirms that, if no agreement is reached by the deadline set by the Contact Group, NATO is ready to take whatever measures are necessary to avert a humanitarian catastrophe. On February 20, 1999 the Contact Group extends negotiations until 1400 GMT on 23 February 1999. On February 23, 1999 the Contact Group gave the parties until 15 March 1999 to approve the Peace Plan in its entirety. Negotiations were conducted in Rambouillet and Paris but were eventually adjourned, due to the unwillingness of the Yugoslav delegation to sign the proposed peace plan.

On 22 March 1999, in response to Belgrade's continued intransigence and repression, and in view of the evolution of the situation on the ground in Kosovo, the NAC authorised the Secretary General to decide, subject to further consultations, on a broader range of air operations if necessary.

On 23 March 1999, all efforts to achieve a negotiated, political solution to the Kosovo crisis having failed, no alternative was open but to take military action. NATO's Secretary General directed the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) to initiate air operations in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Air operations commenced on 24 March 1999 under the nickname "Operation Allied Force".