When the United States entered the war in Vietnam in the 1960s, it had

the world’s most powerful air force. But unlike past wars when the enemy

was clearly defined, the nature of this war was much murkier and there

was hesitation to use airpower to "bomb them back into the Stone Age" as

one general irresponsibly recommended. Throughout the years of the

conflict, generals and government officials often misconstrued the

situation or solution, leading to a confusing policy and eventual

defeat.

The United States promised to support former French Indochina when the

French pulled out of its colony in 1954 after a nine-year war for

independence. Indochina was divided into four countries: Laos, Cambodia,

North Vietnam, and South Vietnam. But North Vietnam quickly became a

communist nation, as one of the leaders of the independence movement,

the charismatic Ho Chi Minh, took control of the nation. In 1959, he

announced he was going to reunify Vietnam as a Communist nation. To

achieve this goal, he gave military assistance to the Viet Cong

(Communist guerrillas in South Vietnam) and began a civil war in South

Vietnam.

In

what was called the "domino theory," the United States believed that if

South Vietnam fell to the Communists, the other democratic nations in

Asia would follow, creating a massive Communist empire. To prevent this,

the United States sent the Military Assistance Advisory Group to the

region in the early 1960s to train the South Vietnam Army to defend

itself. Air force advisors arrived with a variety of planes on which to

train the South Vietnamese Air Force in aerial tactics and techniques.

However the boundaries of this "advisory" capacity began to blur as the

Americans themselves were allowed to fly reconnaissance and close air

support flights against the Viet Cong as long as at least one South

Vietnamese was aboard the plane.

On

August 2, 1964, the USS Maddox, a U.S. Navy destroyer on electronic

intelligence patrol in the Tonkin Gulf, was attacked by three communist

patrol boats. Although the details of the incident were sketchy and

sometimes incorrect, this was the excuse the United States was looking

for to become fully involved. On August 7, Congress passed the Tonkin

Gulf resolution, authorizing President Lyndon B. Johnson to "take all

necessary measures" to repel attacks on the United States. Jets from the

aircraft carriers Ticonderoga and Constellation took off for the first

bombing raids against patrol boat bases and an oil storage depot. The

raids were considered successful, but a plane was lost. The pilot,

Lieutenant Everett Alvarez, Jr., became the first of nearly 600 downed

American airmen who would be held as prisoners of war (POWs) by the

Communists. Alvarez was not released until the peace treaty was signed

eight years later.

Viet Cong raids against American installations began to increase. As a

result, in March 1965, Johnson ordered a bombing campaign, Rolling

Thunder, to break the will of the Communists. U.S. Air Force units

stationed in South Vietnam flew the first raids. The air force requested

two units of Marines to protect their bases. The build-up of U.S.

military units was beginning.

From the beginning, there were many problems with the organization of

Rolling Thunder, making success almost impossible. The targets were

selected during Tuesday lunches at the White House in Washington.

Attending the meetings were President Johnson and his civilian advisors

and beginning in 1967, military representatives. These advisors chose

the targets, tactics, timing, number of aircraft, and ordnance.

Personnel in Vietnam could request targets, but by the time the request

worked its way through Washington, the quick-moving Viet Cong would have

left the area. This micromanagement from across the world by civilian

personnel angered many. Curtis LeMay likened it to a hospital

administrator performing brain surgery.

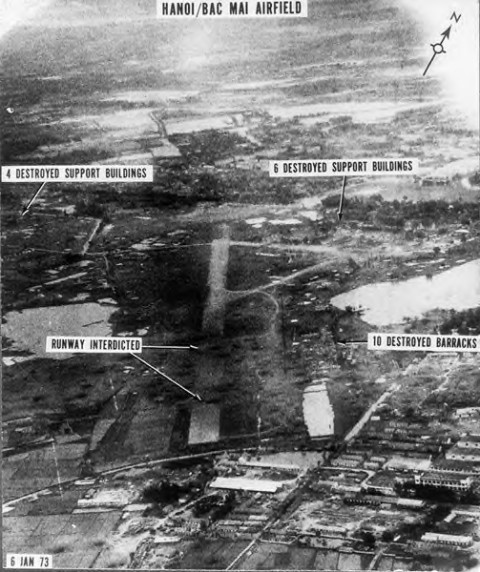

Aerial photo of bomb damage to a

Hanoi airfield.

In

1965, jet aircraft also began to arrive. The first were the Republic

F-105 Thunderchiefs, large fighter-bombers with limited manoeuvrability.

They were soon replaced by McDonnell F-4 Phantom IIs. Descended from the

McDonnell FH-1 Phantom, a single-seat carrier-based jet fighter, design

changes made the F-4 the air force’s main jet-engine fighter. These

two-seaters allowed for weapon system officers (WSOs) who could manage

the planes’ radar systems, especially for air-to-air missiles. The

Phantoms were the only equal to the aircraft the Soviet Union supplied

to the North Vietnamese Air Force with--the MiG-21 Fishbed.

During the Vietnam War, MiG-21s

were often used against U.S. aircraft. Between April 26, 1965, and

January 8, 1973, USAF F-4s and B-52s downed 68 MiG-21s.

Vietnam marked the end of the legend of the ace. There were only five

aces in Vietnam. This was a result of the North Vietnamese pilots

avoiding situations that might involve dogfighting. The rules of

engagement also demanded that U.S. pilots have visual confirmation of

any enemy aircraft before engaging, which was too close for air-to-air

missiles to be effective, and until late in the war the fighters were

not armed with guns. And both the U.S. Air Force and the navy found

their training programs were not good enough for jet-age fighting. After

the war this was remedied with the creation of the Navy Top Gun and the

U.S. Air Force Red Flag programs.

The B-52D, shown dropping bombs

in this photo, was used extensively in Southeast Asia beginning in the

mid-1960s. Operating from Andersen AFB, Guam, and later U-Tapao Royal

Thai Air Base, the B-52 was a major component of many operations

including Arc Light, Iron Hand, Rolling Thunder, Linebacker and

Linebacker II.

Electronic warfare became extremely important in Vietnam. The United

States used large numbers of laser and television-guided bombs to hit

difficult targets. And in 1965, the North Vietnamese began to build a

massive surface-to-air missile (SAM) arsenal. SAM sites were always the

first facilities rebuilt after bombings, although the strict rules of

engagement allowed bombing them only if they were at least 30 miles (48

kilometres) outside a city and their radar was turned on. The American

response was the Wild Weasels. Originally modified F-100 Super Sabres

but later F-4Gs, the Wild Weasels carried equipment to detect

electromagnetic energy in order to identify and destroy SAM sites.

Because they could only detect radar that was turned on, their success

forced the North Vietnamese to discover other ways to aim the SAMs that

would not require activating the radar.

F-105. This Wild Weasel F-105 is

returning from its 100th mission over North Vietnam in November 1968

Airborne warning and controls system (AWACS) planes were also an

essential component of the air war. The first AWACS planes were Lockheed

EC-121s that had been designed to spot Soviet nuclear bombers as they

approached North America. In Vietnam their mission changed to finding

enemy fighters, through radar and interrogating radio transponders, to

determine location and nationality of each plane. They also directed

U.S. aircraft to aerial refuelling tankers and guided rescue planes to

downed pilots. In October 1967, an EC-121 guided a U.S. fighter to the

successful interception of a North Vietnamese MiG-21, the first time an

airborne controller had directed a successful kill.

For many, the Vietnam War evokes the sound of helicopter blades

whirling. Helicopters were involved in all aspects of the war. Bell,

manufacturer of the Bell UH-1 Huey, had hoped to sell 500 of the

helicopter; instead it sold more than 15,000. The Huey was flexible

enough to be used for everything from rescuing downed airmen to cargo.

Airmobile units, considered the most significant ground war development

since tanks, consisted of ground troops transported by helicopters.

Although they demanded a large fleet of helicopters, this style of

warfare made ground troops extremely mobile and effective. Helicopters,

as well as transport aircraft, were also given heavy armament so they

could serve as gunships, which could fly over a target and blast away at

it, relieving pressure on ground troops.

But the question of bombing never went away, even though Rolling Thunder

had ended in November 1968, when North Vietnam agreed to certain

concessions. Bombings did not start up again until North Vietnam sent

mechanized units into South Vietnam in spring of 1972. President Richard

Nixon suspended peace talks and ordered the Linebacker raids to slow

down the enemy’s advance and ruin its logistical support by bombing fuel

depots, bridges, and power plants. By the fall, the North Vietnamese

were severely hindered in its ability to fight but Linebacker was halted

when peace negotiations began again in October. When North Vietnam left

the negotiations in December, Nixon again ordered a bombing campaign.

But this time he brought in B-52s to bomb Hanoi and Haiphong. These

bombings, named Linebacker II, lasted for 11 days until January 1973

when the peace talks resumed. The cease-fire was signed on January 23,

1973. Except for a small contingent to protect American interests,

American troops went home.

Flight from Saigon as

Communists take over in 1975.

In

1975, North Vietnam invaded South Vietnam again, conquering the country

in two months. The United States refused to intervene. As the Communists

approached Saigon, the U.S. ambassador ordered all Americans and some

Vietnamese to evacuate. For 18 hours on April 29, 70 Marine helicopters

evacuated 1,000 Americans and 7,000 Vietnamese from Saigon to aircraft

carriers in the South China Sea. The largest helicopter evacuation in

history closed the book on America’s most disastrous overseas action.