The

first major challenge for the U.S. Air Force and the RAF after it was

named an independent service in 1947 was delivering supplies to Berlin.

The massive airlift was the largest humanitarian operation ever

undertaken by the air force. The more than 2.3 million tons of supplies

flown into the city over approximately 10 months dwarf all future

operations. Even the airlift to war-torn Sarajevo between 1992 and 1997

brought in only 179,910 tons—less than the amount flown into Berlin in

one month alone.

Divided Germany, 1948.

At the

end of World War II, a defeated Germany had been divided into four

sectors, controlled by the United States, the Soviet Union, Great

Britain, and France. The capitol city of Berlin, deep in the Soviet

sector, had been divided in half, with West Berlin controlled by the

western Allies and East Berlin by the Soviets. West Berlin would be

supplied from outside the Soviet sector by roads, railroads, canals, and

three air corridors. The air corridors led to Berlin from the German

cities of Frankfurt, Hanover, and Hamburg and were each 20 miles (32

kilometres) wide.

The

Soviets, though, were acting in an increasingly aggressive manner toward

the capitalist western nations. In 1948, when the western nations

released a new German currency in an attempt to restart the economy in

their sectors, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered his ground troops and

air force to "harass" the supply traffic to Berlin. Then, on June 22,

1948, the seventh anniversary of the Nazi invasion of Russia, all ground

traffic to Berlin was stopped, halting 13,500 tons of daily supplies to

Berlin. Only the air corridors, protected by treaty, remained open.

The

United States, with the U.S. military governor in Germany, General

Lucius D. Clay, wanted to "force the issue" and use troops to escort the

supply convoys through the blockade. But British Foreign Minister Ernest

Brevin proposed a massive airlift that would use military planes to fly

supplies into the city. Berlin needed at least 2,000 tons of supplies

per day for the most basic subsistence. The U.S. Air Force in Europe,

however, had only 100 Douglas C-47 "Gooney Bird" planes available,

barely enough to fly in supplies for Berlin-based U.S. personnel. But

with careful planning and organization, Major General Curtis LeMay,

commander of the U.S. Air Force in Europe, managed to deliver twice the

estimated amount of supplies into the city on a test run, and Clay

decided to try the airlift. LeMay told him to request Douglas C-54

Skymasters from the Pentagon. Skymasters were the air force’s largest

transport plane and could carry four times as much as the C-47s.

"Operation Vittles"-the most

successful peacetime air operation in aviation.

The

first Skymasters arrived at Rhein-Main Air Base in Germany on June 28.

As soon as they landed, they were loaded and sent to Berlin. By the end

of the next week, 300 C-54s had arrived from the Panama Canal Zone,

Alabama, Hawaii, and Texas. The navy sent two squadrons of R5Ds (the

navy’s version of the C-54). The British had already filled its bases

with Dakota, Avro York, and Handley Page Hasting aircraft. By the end of

the summer, civil transports and planes from Australia, South Africa,

and New Zealand had joined the operation. The mission, originally called

the LeMay Coal and Feed Delivery, was renamed Operation Vittles by the

Americans and Operation Plaindafe by the British. The planes took off

from Rhein-Main Air Base and two British bases, flying on the northern

and the southern corridors. They landed in one of three airports and

exited by the centre corridor.

C-47s unloading at Tempelhof

Airport in Berlin. Up to 102 of these planes were flying during the

first three months of the Berlin Airlift.

In

August, General William Tunner, a veteran of supply runs during World

War II over the Hump (between India and China), arrived to direct and

standardize operations to increase efficiency and safety. He discouraged

flying heroics, saying that " a successful airlift is about as glamorous

as drops of water on a stone." And the new flying regulations reflected

this, leaving little room for error. Airplanes took off every three

minutes, around the clock. They maintained that interval throughout the

170-mile (274-kilometers) flight, not veering an inch from the

prescribed route, speed, or altitude. When they arrived in Berlin, they

were allowed only one landing attempt. If they missed it, they had to

transport the load back to base. When each plane landed in Berlin, the

crew stayed in the plane: a snack bar on a wagon gave them food, and

weathermen arrived in jeeps with weather updates. As soon as Germans

unloaded the last bit of cargo, the plane would take off. Back at base,

there was a 1-hour 40-minute turnaround allowed for ground crews to

refuel, reload, do pre-flight preparations, and perform any required

maintenance, which was considerable as the engines experienced rapid and

excessive wear from the short flights. Tires also experienced extreme

stress from the heavy loads and hard landings.

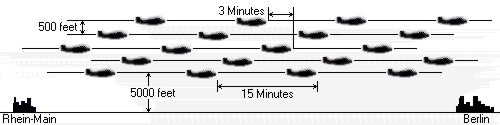

Cross-sectional view of flight

into Berlin as of September 1948.

This arrangement allowed for landing at the rate of one plane every 3

minutes.

Later, two levels were used with spacing that allowed for landing at the

same rate.

The

cargo needed to keep Berlin going included coal, food, medical supplies,

steamrollers, power plant machinery, soap, and newsprint. The U.S. Air

Force’s 525th Fighter Squadron sent the city a gift--a baby camel named

Clarence. Food was dehydrated to decrease weight. And salt, which

corrodes some metals, was flown in by Short Sunderlands, a seaplane with

a corrosion-proof hull. When the seaplane bases froze in winter, the

salt was flown in containers slung externally from Handley Page

Hastings. But coal was the trickiest commodity, although the most

important, comprising 65 percent of the cargo. Coal dust corroded cables

and electrical connections, and crews complained of breathing problems

from inhaling the dust. When the planes had their 1,000-hour overhauls,

their weights had increased by as much as 100 pounds (45 kilograms)--all

coal dust. Eventually, surplus army duffel bags were used to hold the

coal and decrease the dust somewhat.

The

other memorable cargo was candy. At Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport, pilot

Gail Halvorsen one day met some Berlin children who stood at the fences

to watch the planes. Touched by their happiness when he gave them two

pieces of gum, he cajoled his crewmates into pooling their candy

rations. For the next several weeks, they dropped candy to the children,

using handkerchiefs as parachutes and signalling a drop by wiggling the

plane’s wings. A German journalist, having been hit in the head by one

of the packages, wrote a story about the man the children called the

"Candy Bomber" and "Uncle Wiggly-Wings." His secret was out, but

embracing a perfect propaganda story, the air force encouraged his

kindness. The men on base began donating their candy rations and soon

packages of candy, gum, and handkerchiefs arrived from the States. The

project, called Operation Little Vittles, delivered 23 tons of treats to

children all over West Berlin.

On May

12, 1949, after more than 2.3 million tons of cargo, and 277,685

flights, the Soviets relented and reopened the ground routes. In an

effort to end western presence in their territory, they had succeeded

only in embarrassing themselves. The airlift officially ended on

September 30, 1949. During the entire operation 17 American and 7

British planes were lost due to crashes.

For

the U.S. military, however, the Berlin Airlift carried more significance

than victory against a new enemy. The service branches had worked

together, something many had worried would not happen with an

independent air force. And the airlift became a model for future

humanitarian airlifts. Aircraft specifically designed for air cargo

operations were designed based on the lessons of Operation Vittles: the

Lockheed C-130 Hercules, C-141 Starlifter, C-5 Galaxy, and the Boeing

C-17 Globemaster III, which can carry more than 17 times the amount of

cargo as a Skymaster.

Most

importantly, though, the Berlin Airlift began to repair the

psychological wounds of World War II. Less than five years earlier, many

of the same pilots had been dropping bombs on Berlin. Many found it hard

to accept that they were now trying to save the lives of their former

enemies. But they adjusted quickly because, as one airman said, "Somehow

that faceless mass of two million suddenly became individuals just like

my mother and sister." Many, who felt guilt from dropping bombs on

civilians found redemption in helping these same people survive.

Berlin Airlift and modern

airlift aircraft capability comparison.

For

the city of Berlin, destroyed by war and occupation, it was the

beginning of civic pride and integrity. Having feared that the West

would abandon them to starvation, their gratitude still survives. In

1959 they started the Berlin Airlift Foundation to assist the families

of the 78 British and American men killed during the operation. And

during the 50th anniversary celebrations, Berlin citizens signed

parachutes for airlifts to other parts of the world.