|

Europe

takes the

lead and prepares for war

In 1908, the British writer H.G. Wells published War in

the Air, a fantasy that depicted with

frightening clarity the

possibility of cities being bombarded from aircraft

and wars being determined

by air battles. As Europe felt

itself lurching closer and closer to a major war, each of

the possible combatants took stock of their

preparedness in all areas of

warfare, including air power. Even

strategists who believed aviation in the decade before World

War I was the province of

cranks and adventurers, or useful

only for reconnaissance, speculated on what role

an air force might play in

a war and how they would fare

against an airborne enemy. In the

years 1910 to 1914, the French

were certainly the most advanced

in aviation of all the European

nations.

While Europe developed land-based planes

for possible military use, the

American designer

Glenn Curtiss, with U.S. Navy support, was developing

aircraft that could land on and take

off from water.

The International Exposition of

Aerial Locomotion (known as the

Aéro Exhibition) at the

Grand Palais in Paris in October 1909, just weeks after the

spectacle at Reims, made this abundantly clear. Organized by

Robert Esnault-Pelterie, 333 exhibitors displayed their

wares and aircraft, everything from balloons to airplanes to

clothes and accessories; 318 of the exhibitors were French.

On display were the Blériot plane that had made history and

Ader’s Avion of 1897 (which had not); Henry Farman’s aileron-equipped biplane;

Santos-Dumont’s lightweight Demoiselle 20; and (in the most

prominent position in the hall) Esnault-Pelterie’s R.E.P.,

with its revolutionary internally braced wing (doing away

with the need for guide wires) and the first fully enclosed

fuselage.

The French believed that their planes had

developed nicely—the monoplanes they preferred were lighter

and faster than the American biplanes. The Gnome engine,

developed by the brothers Louis and Laurent Seguin in 1909,

was quickly developing into the prototype of the next

generation of airplane power plants, and between 1911 and

1913, French aviators owned virtually every aviation record

on the books.

The two areas in which the French

believed there was room for improvement were raw speed and

manoeuvrability; the Wright aircraft had excelled n both

these aspects of flight at Le Mans and even at Reims, and

these were factors that would be important in military

situations. The French answer in the first area was to

develop flying techniques that took full advantage of

Farman’s ailerons. In September 1913, one of Blériot’s test

pilots, twenty-three-year-old Adolphe Pegoud, a flier so

reckless the press nicknamed him “the fool,” demonstrated

manoeuvres that took flying to an entirely new level.

In spite of the technical

achievements of the Americans, the French influenced

aircraft design profoundly. The graceful and elegant lines

of the

Levasseur-designed Antoinette and the Blériot planes

(such as the Blériot XI shown here) set the course for

future design and

spelled the end of the

Chanute-Wright box kite approach.

His techniques allowed him to fly

upside-down and to perform all manner of loops, rolls, and

turns that were thought to be impossible. One manoeuvre had

the aircraft climb steeply until it stalled, then drop

backwards tail-first, then recover and dive, and then level

off, with the plane describing a Z in the sky. Pegoud became

a celebrated flier in World War I and was shot down in 1915

after a flying career of only three years. Fighter pilots on

both sides during the war openly acknowledged their debt to

Pegoud.

The response to the speed question was to

develop a new kind of airplane construction: the monocoque

fuselage. “Monocoque” means “single shell” and refers to the

fact that the stresses on the wings and fuselage of an

airplane can be borne by the entire shell of the aircraft

instead of by support struts and guy wires, as they were in

the earlier airplanes. The result is a lighter plane with

greater strength and structural integrity. The trail was

blazed by two planes: the Deperdussin, designed by Louis

Bechereau and built by the industrialist Armand Deperdussin;

and the Nieuport, brainchild of engineer Edouard Nieuport.

The Deperdussin, unveiled in 1912, was a sleek aircraft with

a single tractor propeller and was the first plane to

have a monocoque fuselage.

The Nieuport might be looked at as the

step between the Blériot-Voisin planes and the Deperdussin:

it did not use monocoque construction, but it was designed

to have a streamlined, fully enclosed fuselage and a

revolutionary “cowling” or (thecover that enclosed the

engine). These features, plus a flatter wing camber, gave

the aircraft speed and permitted it to set a world speed

record when introduced in 1911. The superiority of the

Deperdussin was believed demonstrated in a race known as the

Circuit of Anjou (after the county in which it was held),

held in June 1912. However, the victory of the Deperdussin

had more to do with the determination of its pilot, Roland

Garros, to fly in stormy weather than with the quality of

the aircraft. In England, aviation had a slow start.

The earliest British planes were built

and flown by an expatriate American, Samuel E Cody, who

seemed for some years to be the only one in England

interested in developing a home-grown airplane. The British

were content to rely on the Wright brothers’ invention,

taking pride that it was based on the pioneering work of Sir

George Cayley, an Englishman. The Short brothers, Oswald,

Horace, and Eustace, became licensees of the Wright patents,

and were soon the major supplier of Wright aircraft to

Europe. Meanwhile, after a brief stint flying man-carrying

kites and dirigibles, “Papa” Cody, as he was called in

the British press (when he first flew in 1908, he was forty

seven years old), turned to aircraft. Cody was a showman in

the tradition of Buffalo Bill Cody (to whom he was not

related), Texas-born and bred and, to all appearances, a

cowboy in a travelling rodeo show.

Yet Cody had an instinctive feel for

airplane design and, with virtually no schooling, he

designed some of England’s first flying machines. The first

flight of an airplane in England was made in his British

Army Airplane No. 1 on October 16, 1908. Ever the showman,

Cody’s airplanes were huge for their time; they were called

“Flying Cathedrals” because of their large wing spans and

their angular shape and pointed canard elevator wing.

Largely at the insistence of hawkish politicians like

Winston Churchill, the British army finally held trials in

April 19 12 at Larkhill for the purpose of evaluating and

commissioning military aircraft.

In spite of the fact that several

designers and builders were already producing noteworthy

aircraft, Cody’s Flying Cathedrals won handily and were the

first planes to be produced at the Royal Aircraft Factory

(formerly a balloon factory) at Farnborough. Samuel Cody

died in a crash on August 7, 1913, while testing one of his

planes. Britain had lost someone as important in promoting

flight in England as Ferber had been in France. Between 1907

and the outbreak of World War in 1914. three Englishmen

entered the field of aviation, working in relative

obscurity, but catching up year by year to the French and

the Americans, and ultimately playing a vital role in both

British aviation and the history of flight.

In 1907, Alliot Verdon Roe (or A.V. Roe,

as he was known) began building small motorized model

airplanes, and by 1 909 he had built the first aircraft made

entirely in England (that is, without French engines in

American designs), the Avro plane, a lightweight tri-plane

that barely flew, powered by a 9-horsepower engine. (At this

time, the Wrights were delivering planes to the U.S. Army

that could fly ten miles [16km] and were powered by 32-

horsepower engines.)

In 1912, Roe introduced the Avro Type F

the first aircraft with a fully enclosed cockpit (an advance

in design, but not a factor in World War I), and in 1913 he

introduced the first of a series of staggered biplanes

(where the upper wing is forward of the lower wing,

streamlining the plane further as it flies) that led to the

Avro 504, one of the most popular and durable planes of

World War I. (Some ten thousand 504s were built and many

remained in service till the mid-1930s.)

Two builders who worked independently before 1912, hut who

made important design contributions at Farnborough, were

Geoffrey de Havilland and Thomas Sopwith. De Havilland was a

designer of buses when he turned to aviation. With the help

of his brother-in-law, engineer Frank Hearle, and his

grandfather’s fortune, de Havilland built and tested his

first plane in 1909— it crashed—and the No. 2 in 1910, which

flew well enough to interest the British War Office in 1911.

The plane was renamed the F.E.1, for “Farman Experimental 1”

because it resembled a Farman biplane. De Havilland adopted

this practice of naming his plane after its inspiration when

he designed the B.E.1, which stood for “Blériot Experimental

1” and which led to the B.S.1 (the Blériot Scout 1), a

staggered-wing biplane with a monocoque fuselage and powered

by a 90- horsepower Gnome engine. The 13.5.1 became an

important fighter in the war and inspired the design of

another classic fighter plane, Tom Sopwith’s Tabloid, which

in turn led to the design of the legendary Sopwith Camel.

By 1910, Germany was convinced that it

had made a terrible mistake in directing all its energies

toward the development of airships at the expense of

airplanes. As it turned out, airships played a more

significant tactical role in World War I than airplanes, and

the absence of native design and building talent made the

Germans more prone to investigate and adapt foreign

expertise— and this resulted in the Germans being very

successful in its wartime air campaigns. The first

heavier-than-air flight in Germany was made by a visiting

Dane, J.C. Ellehammer, and Anthony Fokker. Fokker who was to

become a central figure in German wartime aviation, was

Dutch and had offered his services to the British first.

Völlmöller’s Taube, though it finished second

in the German

Circuit, was clearly a plane Germany would use if war broke

out.

The Germans hastily organized an

aeronautics industry and produced airplanes that owed a

great deal (if not everything) to French planes. The one

pre-war aircraft the Germans built and looked upon as their

own was the Taube (German for “dove”), a 1910 monoplane

designed and built by an Austrian, Igo Etrich, and

originally used by Italy against the Ottoman Turks in Libya.

The plane had a hopelessly outdated birdlike design with a

complex wing-warping system of control. The Taube was

clearly not going to lead to other, more advanced aircraft

and was considered an interim solution at best.

Yet the Taube, outfitted with a Daimler-Mercedes engine, was light

and allowed pilots to hone their flying skills, which would

he tested in the war. In Russia, Igor Sikorsky, a naval

academy graduate, designed, built, and tested the world’s

first practical four- engine airplanes, culminating in the

IIya Mouremetz, a biplane with an enormous wingspan of 113

feet (34.5m), a fully equipped and heated enclosed passenger

cabin, and an odd but usable promenade deck. Eighty planes

built along these lines were proud elements of Czar

Nicholas's air force and were the basis for the Vityaz

bombers, which were among the largest used in the war.

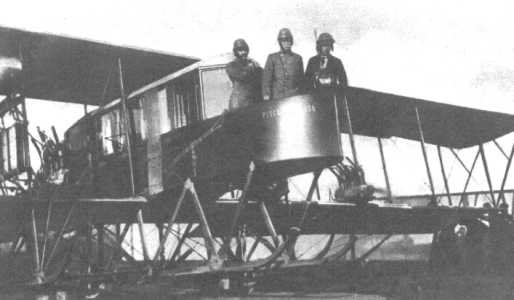

Russians were hard at work developing

large bombers. Sikorsky (right, behind the searchlight)

stands atop the observation deck of the Ilya Mouremetz.

The situation in the United States at this time was, to say

the least, paradoxical. On the one hand, flight had been

developed by Americans to a very advanced stage by the

Wright brothers and Glenn Curtiss, and there was a clear

notion among military leaders that this was a technology the

country had to develop for the sake of national security.

More than ever before, America felt a greater connection to

the rest of the world, particularly to its own western

states and Europe, and flight offered the best prospect of

transporting people across oceans and continents. (And the

entire rambunctious ethos of flight was perfectly suited to

the American mentality and Yankee ingenuity.)

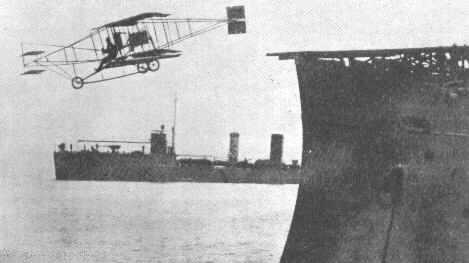

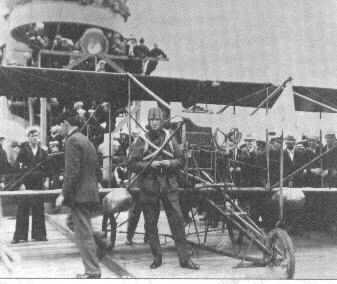

Eugene Ely, a Curtiss exhibition pilot,

makes the first take-off from the deck of

the U.S.S. Birmingham on November 14, 1910.

Ely’s first take-off from and landing on

the deck

of a ship (the U.S.S. Pennsylvania) took place at

the San Francisco Air Meet on January 18, 1911.

On the other hand, President Wilson

was determined to keep America out of the war, and one

element in the strategy to do so was to keep American

forces—forces that could be used to provoke America into

entering the conflict—at minimum strength. The only branch

of the American armed forces that was enlarged for defensive

purposes was the navy. (Ironically, it was the sinking of a

ship, the Lusitania, by a German U-boat, that brought

America into war.)

While the U.S. government

could control procurement and development, it could not halt

progress in design and aviation. American planes developed,

particularly sea- planes, which would play an important role

both in the post-war development of civil aviation and in

naval aviation, particularly in the development of the

aircraft carrier, which would prove critical in World War

II.

American inventors created the first bombsight (Riley Scott

in 1911) and adapted the gyroscope to airplane stability

(Lawrence Sperry installed the gyroscope developed by his

father, Elmer, in a Curtiss seaplane in 1914). Americans had

been first to use radio to communicate with the ground from

an airplane (Baldwin and McCurdy n 1910), accumulating more

experience than anyone else in using radio communication in

flight. And Americans had done the most testing of aerial

bombing and reconnaissance, beginning with Glenn Curtiss’

display on June 30, 1910, of the successful “sinking” of a

dummy battleship on Lake Keuka by dummy chalk bombs (scoring

fifteen direct hits out of seventeen passes).

It was clear as early as 1911 that, while

Europe might momentarily take the lead in aviation, being

confronted directly with the war, America was going to

develop the airplane and its military capabilities at its

own pace, to be used when necessary, either in this war or

the next.

|