the

first U.S. airshows - the

air meets of 1910

Soon after the Reims

Air Meet of August 1909, three major airshows occurred in the United

States that profoundly affected the future of American aviation. In Los

Angeles, Boston, and New York, large crowds turned out to see their first

actual aircraft. Several pilots set new records in a variety of events at

each of the meets, and spectators got to view some dazzling aerial stunts.

The first American airshows created, as some scholars note, a sense of

"air awareness" among those who attended them. Many spectators were

suddenly conscious not only of the airplane's entertainment value but also

some of its utilitarian potential. Notably, the U.S. air meets of 1910

also motivated several would-be pilots, many who would become key figures

during the early exhibition era of aviation, to learn to fly.

Ralph

Johnstone, a member of the Wright exhibition team, set a world record for

altitude,

climbing to 9,712 feet in his Model B at Belmont Park. He consistently

competed against Arch Hoxsey

to set new records. Johnstone died in November 1910 in Denver while

putting on a demonstration flight.

The first major U.S.

airshow took place at Dominguez Field, just south of Los Angeles, from

January 10-20, 1910. The key participants included Glenn Curtiss (the

American hero who had won the prestigious Gordon Bennett Cup race at Reims),

Charles Hamilton (a future American daredevil aviator), Lincoln Beachey

(who was still flying dirigibles at that time, but who would become

America's greatest early exhibition pilot), and Louis Paulhan (a Frenchman

who had started working in a military balloon factory and eventually

taught himself to fly).

Paulhan dominated the

Dominguez meet. First, he set a new flight endurance record by carrying a

passenger almost 110 miles (177 kilometres) in his Farman biplane in 1

hour, 49 minutes. Then he went on to achieve a new altitude mark of

approximately 4,164 feet (1,269 meters). He also performed several aerial

feats during the week, and near the end of the show, carried U.S. Army

Lieutenant Paul Beck aloft to perform one of the first aerial bomb

dropping tests, using weights to simulate the bombs. Overall, Paulhan

ruled the skies over Los Angeles, winning as much as $19,000 in prize

money.

Although the Frenchman

dominated the Los Angeles meet, spectators could celebrate at least a

couple of American victories. Glenn Curtiss set a new air speed record of

approximately 55 miles per hour (89 kilometres per hour), and took home

the prize for the best quick start. In all, he won approximately $6,500.

The Dominguez Air Meet

was highly successful. Spectator turnout numbered somewhere between a

quarter and a half-million people. The Los Angeles Times called it "one of

the greatest public events in the history of the West." Notably, the

Dominguez event also motivated at least one would-be aviator, Lincoln

Beachey, to learn to fly. Although Beachey had begun the meet as a

dirigible pilot, by its end, he had been so inspired by the airplane

pilots that he approached Glenn Curtiss and asked Curtiss to teach him to

fly. Within a year, Beachey would become America's leading exhibition

airplane aviator.

The next significant

American airshow -- the Harvard-Boston Aero Meet--took place at Harvard

Aviation Field in Atlantic, Massachusetts, from September 3-13, 1910. It

was the first major air event in the East and offered aviators more than

$90,000 in prizes and appearance fees. Both the Wright brothers and the

Glenn Curtiss exhibition teams made good showings, but it was the

Englishman Claude Grahame-White, who had become an aviator after being

inspired by Louis Bleriot's historic 1909 English Channel flight, who

ruled the show.

Grahame-White won

several contests at the Massachusetts show, including the speed race, and

won the prizes for the most accurate landing and the shortest take off. He

also gave a bombing demonstration by dropping plaster-of-Paris duds on a

mock warship. The most prestigious event he won was the 33-mile race from

Squantum, Massachusetts, around Boston Light, and back. The winner's purse

was $10,000. Grahame-White won approximately $22,000 in prizes in all

during the meet.

The Massachusetts show

stands out as important not only because it was the first major air meet

in the eastern United States and gave many New Englanders their first real

glimpse of an airplane, but also because it inspired Harriet Quimby, one

of America's most important early women aviators, to pursue her pilot's

license. Sadly however, while the Harvard-Boston meet originally inspired

Quimby to pursue flying, the same venue would take her life two years

later.

Britain´s James Radley sails past the scoreboard in his BlÚriot during the

air meet at Belmont Park.

The last major U.S.

airshow of 1910 took place at a large racetrack on Long Island, in Belmont

Park, New York, from October 22-31. The Belmont International Aviation

Tournament offered approximately $75,000 in prize money and attracted one

of the period's most talented fields of pilots. Events ranged from

competitions for the best altitude, speed, and distance, to contests for

the most precise landing and the best mechanic.

Arch

Hoxsey was one of the aviators to appear at both the 1910 Los Angeles and

Belmont air meets.

He was killed on December 31, 1910, in Los Angeles, while trying to better

his own world altitude record.

More than two dozen of

the world's top aviators attended the New York meet. They came from

England, France, and the United States. The key pilots from France

included Count Jacques de Lesseps and Roland Garros. Claude Grahame-White

from England also attended, as did several Americans--Glenn Curtiss, John

Moisant, Arch Hoxsey, Ralph Johnstone, and Charles Hamilton among them.

Charles

Hamilton, a famous Curtiss exhibition pilot, flew at the 1910 Belmont air

meet.

He always flew carrying a loaded gun and was frequently drunk.

One of the meet's

highlights was an altitude duel between Ralph Johnstone and Arch Hoxsey.

Johnstone eventually won the contest by soaring to approximately 9714 feet

(2961 meters), a new record. Another highlight occurred when Charles

Hamilton won the precision landing event. For a while, it looked as if

Americans might sweep all of the contests, but then the prestigious Gordon

Bennett Cup event, or speed race, took place.

American Walter Brookins competed against Claude Graham-White in the

Gordon Bennett speed race on October 29, 1910,

during the Belmont Air Show, flying his Wright Model "R," known as the

"Baby Grand." He was taken out of the running when he crashed.

On October 29, Claude

Grahame-White flew his Bleriot monoplane to victory in the $5,000 Gordon

Bennett Cup contest in just a little over an hour. He had averaged 61

miles per hour (98 kilometers per hour) over the 100-kilometer race. In

the process, he beat nine other competitors, only three of which even flew

the entire distance. American John Moisant placed second but took more

than an hour longer than Graham-White because of mechanical problems.

Although many contemporaries considered the Gordon Bennett event

aviation's most prestigious race, another showcase contest at Belmont was

just as significant thanks to its $10,000 purse.

Ralph

Johnstone crossing the finish line in air race, 1910.

The meet's final event

was a quick dash that took competitors from the Belmont Park Racetrack,

over New York City Harbour, around the Statue of Liberty, and back. On

October 30, some 75,000 people crowded around the racetrack to witness the

start and finish of the competition. Countless others viewed the contest

from various points around the city.

Once again, Claude

Grahame-White, piloting his 100-hp (75-kilowatt) Bleriot monoplane, put up

the best time and completed the course in 35 minutes, 21 seconds. He

seemed to have won the contest, but then John Moisant surprised him at the

last moment. Moisant had seriously damaged his own plane earlier in the

week and was busy trying to purchase another aircraft while Grahame-White

was winging his way to an apparent victory. At the last minute, however,

Moisant acquired a 50-hp (37-kilowatt) Bleriot and took off in pursuit of

Grahame-White's time. Flying a more direct route than the Englishman

thanks to a new navigational system, Moisant, much to the delight of the

crowd, bettered Grahame-White's mark by 43 seconds. Despite the

Englishman's prestigious victory in the Gordon Bennett race, Moisant was

the meet's hero.

Afterward, Grahame-White

protested Moisant's victory because the American had started the race 21

minutes after the close of allowable start times. Meet officials,

nevertheless, sided with Moisant. After appealing his case all the way to

the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (aviation's main ruling body at

the time), Grahame-White finally achieved his victory when the FAI

reversed the Belmont Park Meet officials' decision in 1912. Graham-White

collected the race's prize money and an additional $500 in interest. For

most of the people who saw the contest firsthand, however, Moisant was the

real victor.

From Los Angeles, to

Boston and New York, Americans had flocked to the American air meets of

1910, gotten their first glimpses of aircraft, and started to contemplate

the future of aviation. In the process, they saw several record-breaking

events and some splendid daredevilry. These first significant American

airshows would prove important to the future of U.S. aviation.

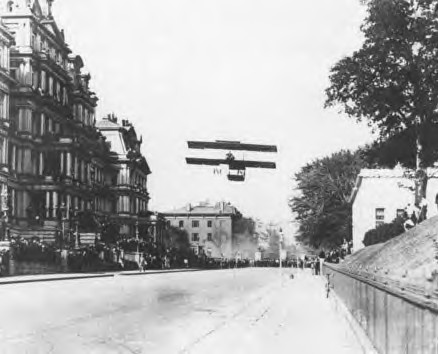

In

October 1910, Claude Grahame-White won the Gordon Bennett speed race at

the Belmont airs meet.

The next month, he flew to Washington, D.C. and landed on a street next to

the White House.

|