guided bombs

It's now known that Germany

deployed a number of more advanced guided strike weapons

that saw combat before either the V-1 or V-2. They were the

radio-controlled Henschel's Hs 293A and Ruhrstahl's SD1400X,

known as "Fritz X," both air-launched, primarily against

ships at sea.

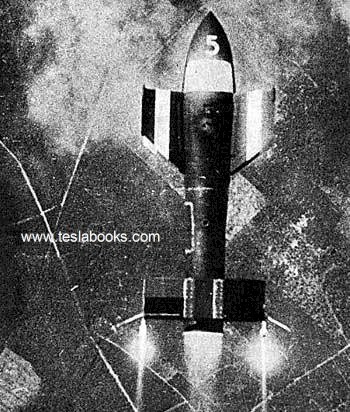

The Ruhrstahl SD 1400 'Fritz X' Air-to-Ship, Wireless

Guided, Gliding Bomb

Of the

fifteen battleships lost to airpower, one of these—the

41,650-ton Italian flagship, Roma—was sunk by a Fritz X. The

British battleship Warspite was put out of commission for 6

months by this weapon. Fritz Xs also hit the cruiser USS

Philadelphia, heavily damaged the cruiser USS Savannah, and

sank the Royal Navy light cruiser Spartan.

A Henschel Hs 293 Air-to-Ship Wireless Guided Bomb with

belly-mounted liquid fuel rocket engine

The Henschel

Hs 293 was responsible for the world's first successful

guided missile attack, sinking the British sloop Egret on

August 27, 1943. The weapon initially possessed an

18-channel radio control system and was flown in the same

way as a radio-controlled airplane. Wire guidance was

subsequently adopted when it was discovered the bomb's radio

receiver was vulnerable to electronic countermeasures.

The

beginning ideas that were to evolve into the Henschel Hs 293

appeared in as early as 1939. In 1940, an experimental model

having the shape of a glider was built. The goal was to

develop a remote-controlled air-to-surface missile against

shipping. Development proceeded even though no suitable

rocket motors were available. The experimental model used a

standard SC 500 bomb with extra wings and tail unit but no

rudder. Finally a propulsion system was developed, and the

liquid rocket was fitted under the main missile body. An

18-channel radio system was used for control.

The missile was designed to be carried under a parent

bomber. Warm exhaust air from the aircraft engines was

channelled to the missile to prevent it from freezing up at

high altitudes. Once dropped the Hs 293 would fall for some

90m (295ft) before the rocket achieved maximum thrust. The

parent bomber would continue to fly a pre-designated course

parallel with the target. The bombardier could visually

track the missile with the aid of red guidance flare in the

tail, and control the projectile using a small control box

with a joystick. The actual flight path resembled a series

of arcs as corrections were received and followed.

The main weakness of the Hs 293A was that the parent bomber

had to fly a steady, level path. Evasive moves to avoid

anti-aircraft fire was impossible, even though the Hs 293

outranged most ship-borne anti-aircraft guns. An improved H2

293D with a television camera installed in the head of the

missile as aiming system was planned but the war concluded

before it could be realized. Also, the problem of icing was

never resolved and thus further propulsion units were

designed. The war ended before these plans left the

experimental stage.

Henschel Hs 293 Air-to-Ship, Wireless Guided, Gliding Bomb

Model C, D or H? carried by a Dornier 217

Crew members learn to control the Henschel Hs 293 guided

bomb in a simulator

During World

War II in the European Theatre the U.S. Air Force

experimented with three basic forms radio-control guided

weapons. In each case, the weapon would be directed to its

target by a crew member on a control plane. The first weapon

was essentially a standard bomb fitted with steering

controls. The next evolution involved the fitting of a bomb

to a glider airframe, one version, the GB-4 having a TV

camera to assist the controller with targeting. The third

class of guided weapon was the remote controlled B-17.

The TDR-1 Assault Drone

Remote-control or "stand-off" weapons were also used in the

Pacific. The TDR-1 Assault Drone carried a 2,000 lb. bomb

load or torpedo, and also included a TV camera for close-in

guidance. The control plane carried a crew of four which

included two pilots who's job it was to control the flight

of the drone.

TBM-1 and TBF-1 Control Plane

On October

27, 1944, a TDR-1 launched and staged a combat attack

against such an enemy target, the success of this system

marking a new era in modern warfare. During the next month,

46 similar attacks were launched against targets in the

Shortland Islands, Bougainville, and Rabaul, with 21 scoring

direct hits. The men behind this remarkable story formed the

STAG-1/SATFOR team, who's vision, determination, and

dedication in performing their secret duties during World

War II laid the groundwork for the modern cruise missile.

Getting Edna III Ready

Another

successful guided weapon, a glide bomb, used in the Pacific

Theatre was the autonomous ASM-2 BAT. It did not use radio

control, rather it incorporated a sophisticated

gyrostabilizer system to keep it on track as it glided

towards its target and an early S-band radar system to home

in on final approach.

The Autonomous ASM-2 BAT

Modern glide

bombs may be guided by laser,

infrared or GPS and have been

used extensively in recent conflicts. The problem still

remains that accurate intelligence is needed to determine

legitimate targets.

When 'Shock and Awe' launched

the first stages of Operation Iraqi Freedom the phrase

became synonymous with a massive military strike—terrifying

and overwhelming. The onslaught of surgically precise

attacks that began on March 21, 2003, was expected to

vaporize the enemy's military and political will and bring

them to their knees. It was a strategy designed to end the

war in hours or days. That was the theory.

The mission was to decapitate the government, destroy

critical buildings and disrupt military communication with

minimal civilian casualties—a tough order in Baghdad, a city

of five and a half million.

The tools for the attack represented a top of the line,

high-tech arsenal: submarine and ship-launched tomahawk

cruise missiles, B-2 stealth bombers and F-117 stealth

fighters, and precision-guided bombs and bunker-busters.

As a military tactic, shock and awe has been tried before

during the last century—though it has rarely succeeded. In

World War I the Germans used zeppelins to cross the English

Channel and drop bombs on Britain, convinced the English

would be stunned into submission. In World War II Hitler's

air force inflicted a 57-day bombing campaign—the Blitz-on

Londoners who once again refused to surrender. The Japanese

also survived and resisted prolonged air attacks—until the

atomic bombs were dropped. Hiroshima and Nagasaki created

both shock and awe.

In the Iraq war, 'Shock and Awe' hoped to generate a similar

psychological blow—without the casualties or the use of

nuclear weapons—via precision-guided bombs.

After Vietnam the sophistication of guided bombs grew

steadily until the public witnessed the grand entrance of

the "smart bomb" during the first Gulf War.

In the early 1990s the American public watched spellbound as

their network and cable news stations bombarded them with a

bird's-eye view of precision guided bombs dropping down

chimneys and slamming through the doors of various Iraq

targets. These bombs gave the impression of clean, precise

warfare. Some of these guided bombs allowed pilots to

control them with a joystick and release the bombs a few

miles from their targets.

But of all the bombs and weapons launched in Iraq in the

first Gulf War, only about seven percent were "smart." And

even these bombs had shortcomings. Laser-guided precision

weapons were accurate, but bad weather or clouds of smoke

from burning oil fields often made it impossible to find

targets. Worse, pilots needed to fly relatively low and

within range of enemy fire.

Just a decade later, 'Shock and Awe' used another advance in

precision bombing—the Global Positioning System, or GPS. GPS

guided bombs, such as the Joint Direct Attack Munition or

JDAM, can be dropped from more than twice the altitude of

earlier guided bombs and from farther away, helping pilots

avoid antiaircraft fire.

On the evening of March 21, 2003, as the deadline passed for

Saddam Hussein and his two sons to leave the country and

avert war with the United States, the weapons of this

hi-tech arsenal were launched.

At 10:15 pm 'Shock and Awe' exploded onto television screens

across the world.

A bizarre testament to the precision of the weapons used

during the first night of 'Shock and Awe' was that the

streetlights still functioned. Electricity flowed to the

city, including the Palestine Hotel where journalists

frantically filed their reports. During the opening days of

the war, even Iraqi government television was untouched and

still broadcasting.

Civilian casualties did occur, but the strikes, for the most

part, were surgical. Some buildings were completely

demolished, while neighbouring structures were untouched.

Some buildings remained standing while their innards were

gutted. In others still, only individual floors were erased.

Even after several days of bombing the Iraqis showed

remarkable resilience. Many continued with their daily

lives, working and shopping, as bombs continued to fall

around them. According to some analysts the military's

attack was perhaps too precise. It did not trigger shock and

awe in the Iraqis and, in the end, the city was only

captured after close combat on the outskirts of Baghdad.

Kamikaze piloted bombs

The history

of kamikaze goes back to the 13th century, when legend has

it that Kublai Khan's invading fleet was turned away from

Japan by a typhoon sent from the gods (kamikaze translates

as "divine wind"). Long thought to be an apocryphal story,

recent archaeological excavations have proven the tale true

(the fleet part, not the gods part), with the discovery of

underwater remains from Khan's fleet.

Suicide has

always been a much larger component of Japanese culture than

in Western civilization, which never really embraced the

idea of "death with honour." Samurai code allowed for the

practice of "seppuku," which was a ritual

self-disembowelment, popularly known in the West as harakiri.

Seppuku was generally used to absolve one's self of some

disgrace or defeat. The suicide mindset continues in Japan

today, where failed businessmen opt for the "honourable" way

out and deranged teenagers take part in Internet suicide

pacts for no special reason. Japan has the highest suicide

rate among industrialized nations, with more deaths by

suicide than by traffic accident.

So when

Japanese fighter pilots during WWII got into dogfights that

were going poorly, they naturally considered the

"honourable" option of crashing their planes into enemy air

fighters. Crashing an airplane into another airplane is

actually trickier than you might think, and generally the

only casualty is the other plane, so air-to-air kamikaze

wasn't really a cost-effective battle strategy.

However,

air-to-water kamikaze was another matter. By late 1944, the

war was not going as well as the Japanese had hoped.

American naval forces were slowly making headway across the

Pacific, and the shores of California were looking farther

and farther away. After some discussion among the brass, the

first formal suicide attack was organized as a volunteer

effort (previous suicide attacks had been spur-of-the-moment

decisions).

The decision to proceed was

motivated in part by an acknowledgement of the Americans'

superior resources and partly for propaganda reasons. The

Japanese assumed, quite reasonably, that U.S. forces would

be unnerved by a military opponent which had zero regard for

its own safety in combat.

In October, the first attack

took place against the U.S. carrier Saint Lo off the coast

of the Philippines. Half of the 26 planes were designated

for suicide; the other half would capitalize on the ensuing

chaos. The attack was a success and the carrier went down.

There was no overwhelming

trend among the volunteers, except that, like modern suicide

bombers, they tended to be young. Although the Japanese

cultural obsession with suicide contributed to the pool of

willing recruits, the effort was also enhanced by the divine

status of the Japanese emperor.

The dominant Shinto religion

holds that the Japanese emperor, like the Egyptian pharaohs

and the Roman Caesars, was a descendant of the gods and a

god in his own right. Although not a doctrinal belief, there

was also a popular notion that kamikaze pilots would earn a

free trip to heaven, just as al Qaeda suicide bombers

believe today.

Japanese pilots were also

trained in special schools, which may have employed

brainwashing techniques to soften up potential kamikaze

pilots for their eventual missions.

By 1945, the tide had

decidedly turned in the Pacific, and the Japanese were in

retreat. In desperation, the number of suicide attacks were

increased, especially in light of their successful

psychological effect on American sailors. Nearly 60 ships

were sunk by kamikaze attacks in the Pacific and Southeast

Asia. Causalities included the USS Bunker Hill and the USS

Essex (pictured in this article).

The kamikaze pilots carried

manuals in their cockpits, which were translated and

published in English in 2002 in the book "Kamikaze: Japan's

Suicide Gods." The books included passages extolling the

spiritual worth of the mission as well as helpful tips in

doing the maximum amount of damage before one's fiery

demise. Some representative passages include:

"Transcend

life and death. When you eliminate all thoughts about life

and death, you will be able to totally disregard your

earthly life. This will also enable you to concentrate your

attention on eradicating the enemy with unwavering

determination, meanwhile reinforcing your excellence in

flight skills......"

"Just as you cannot fight

well on an empty stomach, you cannot deftly manipulate the

control stick if you are suffering from diarrhoea, and

cannot exert calm judgment if you are tormented by

fever....."

"(Just before the crash,)

your speed is at maximum. The plane tends to lift. But you

can prevent this by pushing the elevator control forward

sufficiently to allow for the increase in speed. Do your

best. Push forward with all your might. You have lived for

20 years or more. You must exert your full might for the

last time in your life. Exert supernatural strength."

Although without ceremony

and absolute pre-meditation, many Allied missions both in

the First and Second World Wars were effectively also in

effect kamikaze.

21st Century Kamikaze

In just the

same way as the Japanese resorted to suicide missions when

they no longer were able to field competitive equipment

against their enemy, so there are those whose religion or

culture will allow them to make suicide attacks. Such

attacks are most likely to happen when the cause for action

does not have a standing army or air force, such as

Palestine. The use of hijacked airliners to crash into

designated targets such as happened on the 11th September

will continue to pose a threat.

|