|

the Women Who

Dared the Skies

During World War I, some flight

schools discovered something that

has been noted by air force

training programs throughout the century: women make

exceptional flight instructors,

particularly for male pilots. (The

theory is that the cockier male

pilots are less stubborn and confrontational

with a woman instructor, and are more

receptive to criticism and instruction from her than

from a

man.) The Stinson family of San Antonio, Texas, were

all fliers and the flying school they

founded there trained many

Canadian pilots who went on to serve in the British

Royal Flying Corps.

Marjorie took care of the school

(becoming a legendary flight instructor), while Katherine

supported the school with

stunt flying. Both sisters toured

the country, flying in exhibitions

for Liberty Bonds and the Red

Cross, and Katherine was sent on a

goodwill tour of Japan and

China, where she stunned

men and women alike with her stunt

flying and her liberal attitudes.

Katherine’s flight from San Diego to

San Francisco in 1917 set a non-stop

long-distance record— or

men or women—of 610 miles

(981.5km).

The Stinson sisters retired from

aviation shortly after

the war, but their brother

Eddie continued flying and became a

builder of airplanes that were

widely used in the airmail

service in the interwar period.

The other great woman aviator of the

war years was Ruth Law, also from a family

of aviators. Law was a very

competitive individual, likely to try anything just because

someone told her she couldn’t do

it. Just such a dare was

responsible for her being the second

woman to perform a loop in

1915 (Katherine Stinson being the first, shortly before). She competed in several altitude and distance events,

sometimes winning and

setting records, but always being greeted by adoring

crowds and always demanding

that she be evaluated on the same

basis as male fliers.

At America’s entry into World War

I, Law applied to the United

States Army to fly combat

missions. She bristled when she was

turned down and wrote an

article for Air Travel (“Let Women

Fly!”) that inspired many future

women aviators. After the war,

Ruth Law formed a flying circus and became

one of the most successful

barnstormers of the 1920s. She

retired from flying after one of her women stunt

flyers, Laura Bromwell, was

killed in a stunt.

One of the women inspired by Law was Pheobe

Omlie, who became one of

the greatest barnstormers of the

post-war period. Omlie crusaded for safety markers to assist

aerial navigation and, with

the help of fliers Blanche Noyes

and Louise Thade, flew around the country identifying the

best locations for directional

markers. Omlie

was appointed by President Roosevelt to the National

Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), making

her the first woman to hold a government

post in the field of

aviation.

A Frenchwoman named Adrienne Bolland was the

first to fly a plane from

Argentina to Peru across the

treacherous Andes Mountains in 1921. It would be seven

years before anything comparable was attempted by

women aviators. Many of the women who

performed great feats of

flying and who won races against all competitors resented

being singled out as women and

being praised for flying so well

“for a woman".

This attitude is evident in the reaction of women fliers to

the career of Ruth Elder. Elder was a capable flier who

placed high in the competitive Women’s Air Derby of 1929. In

1927 she announced that she would attempt a crossing of the

Atlantic with her flight instructor, George Haldeman. The

feat was clearly a publicity stunt (as much for the Stinson

Detroiter aircraft they were flying as for Elder) and she

named the airplane American Girl. In the eves of other women

fliers, the photos and the entire project were a throwback

to the days when women were thought to he incapable of

flying.

At the urging of many women aviators, a

second woman flier, Frances Grayson, entered the field,

flying a Sikorsky amphibian, Dawn. But the aircraft of 1927

were not prepared for such a trip—something the

extraordinary flight of Lindbergh earlier only highlighted—

and Elder and Halderman were forced to ditch their Stinson

short of the Azores, near a tanker that rescued them.

Grayson, who insisted on taking the North Atlantic route

instead of the longer but safer South Atlantic course to

Europe, was not as fortunate.

She took off from the coast of

Newfoundland on December 23 and was never heard from again.

A similar conflict surrounded the career of Elinor Smith, an

outstanding flier by any standards, who broke records both

individually and with her fellow woman flier, Evelyn “Bobbi”

Trout. The two fliers teamed up in 1929 and became

well-known for establishing an endurance record and for

performing the first in- light refuelling by women fliers.

In the thirties, Smith billed herself as

the “Flying Flapper” and was widely photographed by

newspapers modelling clothes near airplanes. This did not sit

well with other women aviators. One prominent barnstormer of

the early 1920s was confronted with an additional barrier:

race. Bessie Coleman was born in 1893 in Texas to a poor

black family, but managed to enter college. When she

could no longer afford to stay in college, she

moved to Chicago and decided

to try to learn to fly. After asking virtually

every flight instructor in the country and being

turned down (and having built a

successful business in Chicago),

she went to France and earned a

pilot’s license.

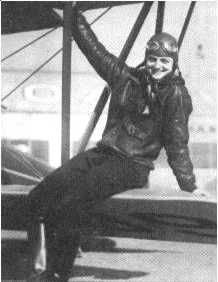

some great women of flight (from the left:

Katherine Stinson in 1916;

Ruth Law, one of the women who came closest to flying combat

missions for the

Allies in World War I, in 1919; and Elinor Smith, an

endurance champ

who flew out of Roosevelt Field, New York, in 1929

She returned to the United States

and began a barnstorming career

that spread her fame throughout

the Midwest. Coleman purposely

flew a Nieuport (a military plane)

and wore military clothes to

emphasize that she could fly a

plane as well as any military pilot.

The participation of the

pre-eminent women aviators

in the 1929 Women’s Air Derby, held at that

year’s Nationals, advanced

the cause of women’s aviation. The

contestants were all accomplished

fliers and record holders: Amelia

Earhart; Ruth Elder; Marvel Crosson

(sister of the famed Arctic

flier Joe Crosson and the only

fatality of the race); Blanche Noyes; Thea Rasche,

the famed German woman

aviator; Bobbi Trout; Florence

“Pancho” Barnes, acknowledged to be

one of the greatest

Hollywood stunt pilots and speed racers, male or female,

of the day; Ruth Nichols;

and the Australian long-distance

flier Jesse Miller.

The course was a long and hard

one, and there was evidence that

resentful individuals had tampered

with some of the equipment. The

winner, Louise (McPhetridge)

Thaden, already a simultaneous

holder of speed, altitude, and

endurance records for women

fliers, was now catapulted into the public spotlight and

became a hero to women everywhere.

Another positive result of the Women’s Air Derby was

the formation of an

association of women fliers called

the Ninety-Nines (after the number of charter members)

which had Amelia Earhart as its first president. The

Ninety-Nines promoted women’s aviation by

lobbying for women to be

allowed to enter air races (women had

been barred in 1930 because of

the death of Crosson, but

were allowed back the following year), and by publishing

The 99-er, a magazine highlighting the latest developments

in aviation and the careers of women fliers. Probably the

greatest triumph in aviation for women during this

period—even more important than the exploits of the great

long- distance fliers—was the victory of Louise Thaden and

Blanche Noyes in winning the Bendix Trophy in 1936.

The pair flew a new design from

Beechcraft, the Model 17 Staggerwing, a biplane with the

lower wing forward of the upper wing (instead of the other

way around, as was the case with most biplanes). They

completed the course hours before their nearest competitor.

The victory had an electrifying effect on women’s aviation;

the victory of Jacqueline Cochran in the 1938 Bendix race

was possible only because of the Thaden-Noyes victory two

years earlier. One could get a rousing argument going about

who was the best woman flier of the Golden Age, but there

wouldn’t he much disagreement about who was the grittiest:

that would be Ruth Nichols. Nichols was born into a wealthy

family and attended the finest schools; she was expected to

enter high society and take her place in the Social

Register. Because of her blue-blood background, she was

called the “Flying Debutante” by the press, a name she

hated.

Louise Thadden was among the

most accomplished aviators of her day,

wining the 1936 Bendix Trophy in a

Beechcraft Model 17

Staggerwing.

Ruth

Nichols seems a tad overdressed to pilot

her Vega for a 1931 test flight, but she

as as rugged and determined as any flyer

of the period.

Bessie Coleman,

in a 1923 photo

became the first black woman

aviator

but she had to go to

England to get her license.

As

a graduation present, her stockbroker father treated her to

a ride in a barnstormer’s airplane, and as she would write

years later, “I haven’t come down to earth since.” While

vacationing in Florida during a break from her studies at

Wellesley, she took lessons from a barnstormer named Harry

Rogers, and she soon abandoned plans to enter medical school

and took up flying. Her big break came when Rogers asked her

to be his copilot in an attempt at a record-setting run from

New York to Miami in 1928. She was instantly propelled into

the spotlight and was able to dedicate herself to flying

full-time. She became a spokesperson for the Fairchild

Airplane and Engine Company and toured the country in her

trademark custom-made purple leather flight suit and helmet.

With a Lockheed Vega borrowed from radio

manufacturer Powel Crosley, and coached by Charles

Chamberlain, the noted test pilot for Whirlwind, Nichols set

several records in cross-country flying and altitude in

preparation for a solo flight to Paris along Lindbergh’s

route. Naming the plane the Akita (an Indian word meaning

“to explore”), she took off from New York on June 22, 1931,

to cross the Atlantic. Instead of stopping to refuel in

Portland, Maine, she went to an alternate site, St. John,

New Brunswick, with which she was unfamiliar.

The runway was

too short for so fast a plane and the Lockheed ploughed into

the forest at the end of the field. Nichols was badly

injured—she cracked five vertebrae—and was told it would be

a year before she could fly again, and even then only with a

thick steel body brace. But only a month later, Nichols was

supervising the repairs to the Akita and, still in her

plaster cast, preparing to take another run at the Atlantic.

The weather would not cooperate and, after a month’s delay,

she decided instead to try to beat the non-stop solo overland

distance record of 1,849 miles (2,958.4km) set by French

flier Maryse Bastie. This time, there would be nothing left

to chance.

She flew from New York to California, stopping at

each potential landing site along the way to become familiar

with the runways and the terrain. She took off from Oakland

and made it as far as Louisville, Kentucky, short of her

goal but still just breaking Bastie’s record. As she took

off to finish her journey, a leaking valve caught fire.

Nichols managed to land the plane and, now in her heavy and

cumbersome steel body brace, to climb out and leap clear

just as the plane exploded. The Akita was demolished, and

thus ended Nichols’ plans to cross the Atlantic.

|