Ormer Locklear, one of

the main barnstormers of the 1910s and the "King of the Wing Walkers," was

Hollywood's first major stunt pilot. One of the key tricks that Locklear

created was "the transfer," a stunt where a pilot switched from one plane

to another in mid-air or from a speeding vehicle such as a car onto an

aircraft. In 1919, Locklear performed the first car-to-plane transfer on

film in the movie The Great Air Robbery. One year later, he filmed The

Skywayman. The movie's main stunt called for a night time crash. Locklear

attached magnesium flares to his plane to simulate an aircraft going down

in flames. While performing the manoeuvre, Locklear's plane went into a

spin and he crashed. Many historians believe that the movie studio's

searchlights temporarily blinded him during the stunt and caused the

mishap that killed him.

Frank Clarke was the

next major Hollywood stunt pilot to gain prominence. In 1921, Clarke

performed a particularly risky stunt for the film Stranger Than Fiction.

The feat involved flying a Curtiss Canuck biplane off a 10-story building

with only a 100-foot (30-meter) runway. During the trick, the airplane

almost dropped onto the street below before Clarke gained enough power to

level off. Clarke would go on to be the chief pilot for Howard Hughes'

1929 film Hell's Angels, which included more than 50 World War I airplanes

and over 100 pilots. Several stunt men died during the making of the film,

but Clarke survived and continued to work until June 1948 when he died in

a non-job-related plane crash.

During the early years

of Hollywood, stunt pilots were essentially self-employed fliers. In 1924,

three stuntmen, Ronald MacDougall, Ken Nichols, and William Matlock joined

forces and formed a stunt pilot's union that they called "The Black Cats"

because of the black cat emblem on the side of MacDougall's plane. Ten

more pilots would eventually join the group, making the organization the

"Thirteen Black Cats." The Black Cats were the first group to develop a

set wage scale for aerial stunt work. Prices ranged from as little as $100

for a mid-air transfer to as much as $1200 for crashing an airplane or

$1500 for blowing up an aircraft in mid-air and parachuting out. Although

the Black Cats worked on several movies, by the end of the 1920s, most of

them had either died or moved on to other pursuits. Their organization,

however, provided a model for the more formal union that would soon

follow.

By the beginning of

the 1930s, many stunt pilots wanted to establish some safety guidelines

for the industry, as well as a guaranteed wage scale and an insurance plan

to pay their medical bills. In September 1931, several pilots met at

Pancho Barnes' house. Barnes, Hollywood's first female stunt flier, was

particularly interested in organizing a formal union, and she got her wish

when they formed the Associated Motion Picture Pilots (AMPP). Working with

a wage scale based on the Black Cats' fees, the AMPP took control of the

industry's stunt work. As Hollywood aviation historians Jim and Maxine

Greenwood have noted, the AMPP established "a virtual monopoly on motion

picture flying."

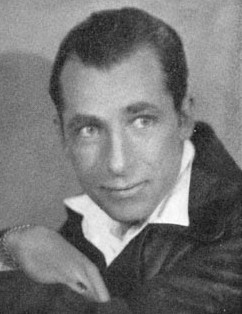

Dick Grace

Dick Grace was an

original member of the AMPP and one of Hollywood's most famous stunt

pilots. He specialized in controlled airplane crashes. During his career,

which lasted from the 1920s to the 1960s, Grace performed between 45-50

crashes. Grace first gained widespread notice by performing four major

crashes for the movie Wings. On his fourth and final crack-up for the film,

he broke his neck but survived after spending several months in the

hospital. Returning to work, Grace went on to do several stunts for Hell's

Angels. Another career highlights included his innovative design of a

special lap and shoulder harness to secure him during crashes. By the end

of his stunting days, Grace had broken more than 80 bones in his body.

Nevertheless, as dangerous as Grace's particular specialty was, he still

lived to the age of 67 and was one of the few stunt men who did not die in

an airplane. In June 1965, Grace died of emphysema in bed.

Paul Mantz

Paul Mantz is

undoubtedly the most famous stunt flier in Hollywood history. Mantz earned

more than $10 million during his career. Shortly after washing out of Army

Flight School in 1927 for buzzing a railroad car, Mantz moved to

California and started his own charter air service. He originally found it

difficult to break into movies because he was not a member of AMPP. To get

union officials to notice him, he set a new world record of 46 consecutive

outside loops in July 1930. Soon after, he became a union member. Although

Mantz performed many stunts, he specialized in flying through buildings.

In 1932, he guided a Stearman plane through a 45-foot-wide aircraft hangar

for the film Air Mail. Notably, in a different facet of his aviation

career, Mantz won the Bendix Trophy Race three times between 1946 and

1948.

By the late 1950s,

although Mantz was still Hollywood's leading individual stunt pilot, he

decided to join forces with another outstanding stunt flier named Frank

Tallman. Together, the two men formed Tallmantz Aviation in 1961, a new

stunt flying operation. Tallman did some of his most outstanding

individual stunt work for the 1963 movie It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, World.

Some of his stunts included taxing through a plate glass window and flying

a plane though an aircraft hanger. The most elaborate trick he performed

for the film was flying an airplane through a billboard.

Mantz and Tallman's

collaboration did not last long. In 1965, the two men were working on the

movie Flight of the Phoenix when Tallman, who was supposed to fly a

landing sequence in the Arizona desert, shattered his kneecap during a

fall at home, and Mantz took his place. On July 8, Mantz was performing

the landing when one of his aircraft's wheels hit a small, sun-baked,

mound of sand and caused him to lose control. The aircraft "nosed in"

killing Mantz instantly. Tallman, heartbroken by the accident, blamed

himself for Mantz's death.

the Phoenix crash site

A few days after

Mantz's crash, Tallman faced his own individual tragedy when doctors

amputated his leg because of a massive infection that had resulted from

his broken kneecap. Despite the loss of his leg and his close friend,

Tallman re-taught himself how to fly using only one leg and returned to

stunting. In subsequent years he worked on such films as The Blue Max,

Catch 22, The Great Waldo Pepper, and Capricorn One. On April 15, 1978,

Tallman, age 58, lost his life during a routine flight when he failed to

clear a ridge near Palm Springs, California, due to poor visibility.

Many other Hollywood

aviators have established their own unique stunts over the years. Some

have specialized in parachute stunts. Others, like Jim Gavin, have become

experts at performing helicopter tricks. And still others have worked with

such unique devices as "rocketbelts." Undoubtedly, there will be many more

stunt pilots who will go even farther than these performers, and each will

owe a debt to their predecessors. Thanks to the pioneering aviators of the

movie industry, future stunt fliers will have a strong union, strict

safety guidelines, and guaranteed wage scales that will help them succeed

in the movie business and movie goers will continue to be treated to many

more aerial thrills.