|

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA)

From March 3, 1915 until

October 1, 1958, the National Advisory Committee for

Aeronautics (NACA) provided advice and carried out much of

the cutting-edge research in aeronautics in the United

States. Modeled on the British Advisory Committee for

Aeronautics, the advisory committee was created by President

Woodrow Wilson in an effort to organize American

aeronautical research and raise it to the level of European

aviation. Its charter and $5,000 initial appropriation (low

even for 1915) were appended to a naval appropriations bill

and passed with little notice. The committee's mission was

to "direct and conduct research and experimentation in

aeronautics, with a view to their practical solution."

John F. Victory (1892-1974) was the NACA's first employee

and the only executive secretary it ever had.

The NACA was involved in

virtually all areas of aeronautics. Initially consisting of

12 unpaid members, in its first decade it counselled the

federal government on several aviation-related issues. These

included recommending the inauguration of airmail service

and studying the feasibility of flying the mail at night.

During World War I, the NACA recommended creating the

Manufacturers Aircraft Association to implement

cross-licensing of aeronautics patents. The NACA proposed

establishing a Bureau of Aeronautics in the Commerce

Department, granting funds to the Weather Bureau to promote

safety in aerial navigation, licensing of pilots, aircraft

inspection, and expanding airmail. It also made

recommendations to President Calvin Coolidge's Morrow Board

in 1925 that led to passage of the Air Commerce Act of 1926,

the first federal legislation regulating civil aeronautics.

It continued to provide policy recommendations on the

Nation's aviation system until its incorporation in the

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in

1958.

From its origins, the NACA

emphasized research and development. Although the Wright

brothers had flown successfully in 1903, by 1915 the United

States lagged far behind European aviation capabilities, a

situation many aviation advocates in the United States found

galling. The United States trailed Europe in its

accomplishments, its lack of organized research, and also in

the amount of funds allocated to military aviation. To help

resolve these problems, in 1917, the NACA established the

Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory in Virginia. This

laboratory would become the most advanced aeronautical test

and experimentation facility in the world.

Langley Laboratory's first wind tunnel, built in 1920.

By 1920, the NACA had

emerged as a small, loosely organized group of leading-edge

scientists and engineers that provided aeronautical research

services equally to all. It had an exceptionally small

headquarters staff that oversaw the political situation and

secured funding for research activities.

Put into operation at Langley in 1922, the Variable Density

Tunnel was

the first pressurized wind tunnel in the world.

It could achieve more realistic effects than any previous

wind tunnel

in predicting how actual aircraft would perform under flight

conditions. Today it is a National Historic Landmark.

Its unpaid appointed

governing committee made the committee one of the most

non-traditional and non-bureaucratic organizations in

Washington. Moreover, its small Langley Laboratory, with

only 100 employees by 1925, conducted pure research, mostly

related to aerodynamics, receiving advice and support from

the headquarters director of research, Dr. George W. Lewis.

Researchers could develop their own research programs along

lines that seemed the most productive to them, handle all

test details in-house, and conduct experiments as they

believed appropriate. Their "Technical Notes" and "Technical

Reports" presented their interim and final research

findings. Old NACA hands believed that their independence

from political pressures was partly the reason that NACA was

the premier aeronautical research institution in the world

during the 1920s and 1930s.

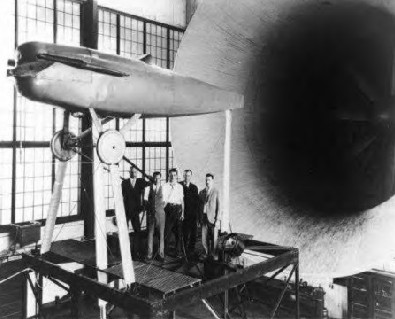

These five men were on the NACA's Propeller Research Tunnel

engineering staff in 1928.

Shown (left to right) are Fred Weick, Ray Windler, William

Herrnstein, Jr., John Crigler, and Donald Wood.

This group conducted the cowling research work that won the

NACA its first Collier Trophy.

NACA was a valuable

disseminator of information to designers and manufacturers.

Research results distributed by the committee influenced

American aviation technology, and its reports served as the

basis for many innovations that were built into American

civil and military aircraft.

The NACA cowling fitted on a Curtiss Hawk, 1928.

In 1925, NACA's director

George Lewis launched construction of a wind tunnel large

enough to accommodate a full-size fuselage with an engine.

Fred Weick, the NACA's propeller expert, used this tunnel to

study the relationship between engine cowlings and drag. The

result was the low-drag streamlined cowling for aircraft

engines, which all aircraft manufacturers adopted. This

innovation would greatly reduce the drag that an exposed

engine generated and would result in significant cost

savings. The innovation won the NACA Collier Trophy for

1929. NACA engineers also demonstrated the advantages of

mounting engines into the leading edge of a wing of

multiengine aircraft rather than suspending them below,

which manufacturers also quickly adopted.

Airfoil research was also

a major focus. NACA engineers tested 78 airfoil shapes in

its wind tunnels and in 1933 issued Technical Report No.

460, "The Characteristics of 78 Related Airfoil Sections

from Tests in the Variable-Density Wind Tunnel." The authors

of this report described a four-digit scheme that defined

and classified the shape of the airfoil. The testing data

gave aircraft manufacturers a wide selection of airfoils

from which to choose. The information in this report

eventually found its way into the designs of many U.S.

aircraft of the time, including a number of important World

War II-era aircraft.

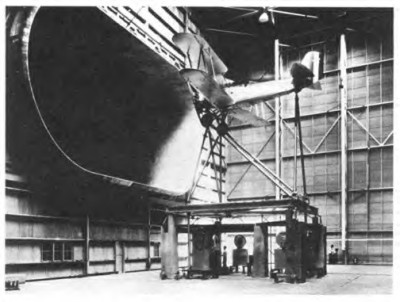

A Vought O3U set up for tests using the full scale wind

tunnel at Langley, completed in 1931.

The Langley laboratory

continued to design new wind tunnels that added to its

capabilities, building about a dozen tunnels by 1958. In

1928, the first refrigerated wind tunnel for research on

prevention of icing of wings and propellers began

operations. In 1939 the NACA constructed a new

low-turbulence two-dimensional wind tunnel that was

exclusively dedicated to airfoil testing. A transonic tunnel

in the early 1950s provided data for Richard Whitcomb's

research into supersonic flight.

In 1940, NACA established

the Moffett Field Laboratory near San Francisco as an

aircraft research laboratory. It was renamed Ames

Aeronautical Laboratory for Joseph F. Ames, a chairman of

NACA, in 1944. Also in 1940, Congress authorized the

construction of an aircraft engine research laboratory near

Cleveland, Ohio. Dedicated in 1943, it became Lewis Research

Centre in 1948, named after George Lewis, former NACA

director of aeronautical research. The NACA also established

the Wallops Flight Centre on the eastern shore of Virginia

in 1945 as a site for research with rocket-propelled models

and as a centre for aerodynamic research. A temporary

Langley outpost at Muroc, California, became a permanent

facility known as the NACA Muroc Flight Test Unit in 1946.

In 1949, it became the NACA High Speed Flight Research

Station and in 1954, became independent from Langley.

NACA made a major contribution to aviation with its

classification of airfoils. This shows the change in airfoil

shape from the Wright brothers (1908) to more modern times

(1944). Much of the data was obtained through wind tunnel

testing.

Before the outbreak of

World War II, NACA's research had both military and civil

applications. During the war, however, its activity became

almost exclusively military and its ties with industry also

became much stronger. In 1939, the first industry

representative, George Mead, president of United Aircraft

Corporation, joined the executive committee as

vice-chairman. Dozens of corporate representatives would

visit Langley during the war to observe and actually assist

in testing.

During the war, the NACA

focused more on refining and solving specific problems

rather than on advancing aeronautical knowledge. A major

advance, however, was the development of the laminar-flow

airfoil, which solved the problem of turbulence at the wing

trailing edge that had limited aircraft performance.

The NACA also contributed

to the development of the swept-back wing. In January 1945,

Robert T. Jones, a NACA aeronautical scientist, formulated a

swept-back-wing concept to overcome shockwave effects at

critical Mach numbers. He verified it in wind-tunnel

experiments in March and issued a technical note in June.

His findings were confirmed when German files on swept-wing

research were recovered and by German aerodynamicists who

came to the United States at the close of the war.

High-speed flight research

after the war was often a collaboration between the NACA and

the U.S. Army Air Force. The first glide flight of the

AAF-NACA XS-1 rocket research airplane took place in January

1946. Breaking of the sound barrier followed on November 14,

1947. Record flights by rocket planes by the military and

the NACA probed the characteristics of high-speed

aerodynamics and stresses on aircraft structures. NACA's

John Stack led the development of a supersonic wind tunnel,

speeding the advent of operational supersonic aircraft. He

shared the Collier Trophy in 1947 with Chuck Yeager and

Lawrence Bell for research to determine the physical laws

affecting supersonic flight.

This photo displays typical high-speed research aircraft

that made headlines at Muroc Flight Centre in the 1950s.

Clockwise from lower left: the Bell X-1A, Douglas D-558-a

Skystreak, Convair XF92-A, Bell X-5 with variable sweepback

wings,

Douglas D-558-II Skyrocket, Northrop X-4, and the Douglas

X-3 in the centre.

At Lewis, NACA translated

German documents on jet propulsion tests that became basic

references in the new field of gas turbine research. Italian

and German professionals came to Lewis to work with their

American colleagues in these new aspects of flight research.

To cope with continuing problems of how to cool turbine

blades in the new turbojets, another German, Ernst Eckert,

at Lewis laid the basic foundation for research into the

world of heat transfer.

In December 1951, Richard

T. Whitcomb verified his "area rule" in the NACA's new

transonic wind tunnel. Useful in the design of delta-wing

planes flying in the transonic or supersonic range, the rule

stated that, to reduce drag, the cross-sectional area of the

aircraft should be consistent from the front of the plane to

the back. The resulting "Coke bottle" or "wasp waist"

fuselage shape was contrary to the design customary at that

time that had the cross-section much greater where the wings

were attached to the fuselage. Designers quickly applied the

supersonic area rule to the design of new supersonic

aircraft.

In 1952, the NACA was

already thinking about aircraft that went very high and had

to re-enter the Earth's atmosphere at a high rate of speed,

producing a great deal of heat. That year, H. Julian Allen

of Ames conceived the "blunt nose principle," which

suggested that a blunt shape would absorb only a very small

fraction of the heat generated by the re-entry of a body into

the Earth's atmosphere. The principle was later significant

to intercontinental ballistic missile nose cone and NASA

Mercury capsule development.

The NACA was also

considering flight beyond the atmosphere. In 1952, the

laboratories began studying problems likely to be

encountered in space. In May 1954, the NACA came out in

favour of a piloted research vehicle and proposed to the Air

Force the development of such a vehicle. The NACA also

studied the problems of flight in the upper atmosphere and

at hypersonic speeds, which would lead to the development of

the rocket-propelled X-15 research airplane.

The NACA ceased to exist

on October 1, 1958. It was succeeded by the National

Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which was

formed largely in response to Soviet space achievements.

NACA became the nucleus of the new agency, and all NACA

activities and facilities were folded into NASA. The major

focus became space research, but aeronautics would remain as

the first "A" in its name.

|