In the first months after the Japanese

attack of Pearl Harbour, the US watched Japan taking over south east Asia

and could not do anything about it. The US began to build an unstoppable

military force, but until it became operational, something was desperately

needed to boost morale, to demonstrate to enemies and allies alike that

the US is striking back.

The way to do it was by air. Several

proposals to attack Japan itself by air were rejected. The US lost its air

bases in the Philippines, and sending the few remaining aircraft carriers

to within strike range from Japan was much too risky. However, a young

navy officer suggested to attack Japan with medium bombers which would

take-off from an aircraft carrier. It was a daring idea, perhaps

impossible, so Admiral King asked his air operations advisor to study the

possibilities. After five days of careful calculations, the admiral

received a 30-page report, hand-written for secrecy. After considering all

the technical aspects of range, winds, weight, armament, fuel, and route,

the conclusion was that the mission is doable, but the bombers will not be

able to return to the aircraft carrier. Instead they will have to land

somewhere in Asia.

Since medium bombers were in the army

air force, the project was then passed to it, and General Henry Arnold

appointed Lt. Colonel James H. Doolittle as the mission commander.

Doolittle was the right person for this extraordinary and technically

difficult mission. At age 45, Doolittle was not just an excellent and

highly experienced pilot, he also had a doctorate from M.I.T .

Doolittle's first task was to select the

right aircraft for the mission. A bomber capable of taking off from the

very short runway of an aircraft carrier, carry 2000lb of bombs, and fly a

very long range of 2400 nautical miles. He selected the twin-engined B-25B

Mitchell. 16 bombers will participate in the mission.

The bombers still had to be modified for

the near impossible mission. The bombers were stripped from anything that

was not essential, in order to make room for extra fuel and reduce weight.

A 200 gallons rubber fuel tank was installed in the bombs compartment,

another 160 gallons fuel tank was put in the crew corridor, and a 60

gallons fuel tank replaced the machine guns in the the ventral turret.

Finally, ten 5 gallon tanks were also taken, to be manually added into the

rear fuel tank in flight. The total amount of fuel was almost double than

that of a standard B-25. The 230lb radio was removed, and so was the top

secret Norden bombsight. The engines were optimized for maximum fuel

efficiency.

Beside the technical preparations,

Doolittle also selected the crews, all volunteers, for the 16 bombers. The

crews flew to Eglin, Florida, for intensive training in short takeoffs and

landings, navigation, low altitude bombardment, and fuel efficient flying.

Following the training, some pilots were able to take off after just 120

meters. The gunners also trained in using their guns for ground combat

after landing. Everyone knew they were training for a high risk special

mission, but although Doolittle announced several times during the

training that they can leave the mission, no one did.

In March 25, 1942, the bombers flew to

California and were loaded on the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. A week

later, the Hornet's carrier group (1 carrier, 2 cruisers, 3 destroyers, 1

tanker) sailed into the pacific ocean. Secrecy was such that only two men

in the Hornet knew where they were heading, Doolittle, and the Hornet's

captain. Several hours later Captain Mitchner announced to the entire crew

:

"Attention ! The target is Tokyo !"

The bomber crews now received their

first briefing about the mission details. Doolittle will takeoff first,

alone, and will attack Tokyo at dusk. The fire from his bombs would help

the following crews navigate. The remaining 15 bombers, in 5 formations of

three, were given industry and energy targets in north, centre, and south

Tokyo, and also in nearby Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. They were supposed to

take off 400 miles from Japan, and after dropping their bombs, use the

darkness to escape, and head to china, to an area which was not under

Japanese occupation, and land there in a specially prepared airstrip.

In April 13, eleven days after leaving

California, the Hornet's group met the carrier group of the USS

Enterprise, and they continued together as Task Force 16, commanded by

Admiral Halsey. The Enterprise air group provided air cover, and two

submarines led ahead of the force, looking for Japanese vessels. Four days

later, in the north pacific, the tankers and destroyers left the task

force, and the carriers and four escorting cruisers increased their speed

and headed to Japan. Takeoff was scheduled for April 19 in the afternoon,

but in April 18, 1942, at dawn, the task force was detected by a Japanese

patrol boat. It was quickly sunk by one of the cruisers, but it was

correctly assumed that their presence was already reported to Tokyo. (Japanese wartime documents reveal that the Japanese patrol boat did report

that it met an American carrier group, but the report was ignored in

disbelief... )

The early detection was a major

difficulty. On one hand the carriers were still over 600 nautical miles

from Japan, and fuel was already a problem. On the other hand Admiral

Halsey knew that the group may be attacked by Japanese carrier aircraft.

At 8AM he ordered Doolittle's raiders to takeoff immediately.

The crews rushed to their bombers. The

Hornet turned into the strong wind. Engines were started. Doolittle

released the brakes and after a short run his bomber was airborne. All the

16 bombers successfully took off, and then the carrier task force quickly

turned, heading back to Pearl Harbour.

Flight over the ocean was normal. Near

Tokyo, flying at very low altitude, the Doolittle raid bombers met several

formations of training aircraft, but no fighters, and no anti-aircraft

fire. Their surprise was perfect. It was noon, and Doolittle climbed to

1200ft and dropped his first bomb over the centre of Tokyo. Soon after all

the other bombers bombed their targets.

Tokyo was stunned. People panicked.

After repeated promises by the authorities that Japan's sky will be

'clean' forever, the Doolittle raid was a shock to Japan's military and

population. The heads of the air force and navy accused each other, and

the commander of Tokyo's air defence committed a suicide.

The Doolittle raid was already a

success, but the 16 bomber crews still had a long way ahead. They flew

towards China. It became dark and cloudy. Doolittle climbed over the cloud

cover and kept flying in total darkness. His attempt to locate the planned

Chinese navigation beacon failed. After 13 hours of flight, Jimmy

Doolittle and his crew abandoned their aircraft and parachuted into the

night.

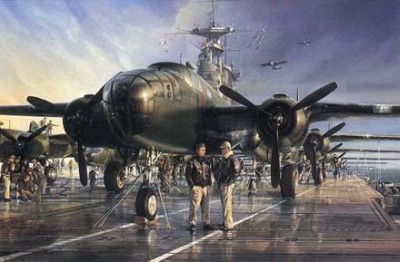

Major General James Doolittle’s raid on Tokyo. Yokosuka Japan Naval base

taken from B-25, April 18, 1942

In the morning Doolittle found a Chinese

peasant who brought him to a Chinese officer who initially refused to

believe his fantastic story, but eventually agreed to let him call the

Chinese headquarters, and they delivered the message to Washington that

the Doolittle raid was a success.

The news electrified America and morale

boosted high. To increase Japanese confusion, president Roosevelt declared

that the bombers that struck Japan took off from Shangri-La, a virtual

place in the Himalayas.

The destiny of the other bomber crews

was similar to Doolittle's. The aircraft sent to bring their reception

team and the homing beacon crashed a day earlier, and so all but one crew

parachuted or crash-landed in various places in China that night. Most of

them returned home, but eight were captured by Japanese forces ( 3 were

executed, 1 died in Japanese prison camp, 4 remained POWs until the end of

the war).

One crew, that had higher fuel

consumption and could not reach china, turned north and landed in a soviet

airstrip. The crew was arrested ( at that time the soviet union was still

'neutral', hostile to both the US and Japan, and the German invasion that

made the US and USSR allies was still 3 months in the future ).

The Doolittle raid's results

The raid on Tokyo was a great success.

The material damage was small, but the effect on morale, both in the US

and in Japan, was significant and important. Furthermore, because of the

attack the Japanese air force transferred four fighter squadrons from the

war front to air defence of the Japanese home islands. The Japanese army

massacred the civilian population in the regions of the bomber landings as

a punishment.

The most important result was that the

raid ended the strategic disagreement in the Japanese high command,

between Admiral Yamamoto, who claimed that Japan will not be able to

achieve its goals without decisively defeating the US pacific fleet,

Admiral Nagano who proposed to attack Australia and India, and the army

generals who wanted to continue to focus in China. The Doolittle raid

proved that Yamamoto was right, and that led to the Japanese attack at

Midway, which was intended to draw the American aircraft carriers to a

decisive battle and sink them.

The battle of Midway was indeed

decisive, but thanks to the achievements of the US navy's code-breakers

who provided an effective warning, it was the Japanese navy who lost its

aircraft carriers in it. It was was the end of the Japanese navy's

superiority.

Jimmy Doolittle received the

Congressional Medal of Honour for planning and leading the Tokyo Raid. He

was promoted to General, and later in the war vast bomber fleets under his

command dropped countless bombs on Germany and Japan, but he is best

remember for the first four bombs he dropped over Tokyo in April 1942,

America's first victory.