The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk was

flown in China early in 1942 by the famed Flying Tigers.

In

1937, Japan invaded China. The Chinese government looked to the United

States for assistance, hiring U.S. Army Air Corps veteran Claire

Chennault to train its pilots. Chennault was a leading developer of

combat tactics for pursuit aircraft whose ideas had fallen out of favour.

When he was forced to retire in 1937 from the Air Tactical School

because of bronchitis, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, the head of the Chinese

Air Force, offered him the job. He accepted and left for China, where

his health rapidly improved.

Major Gen. Claire L.

Chennault.

Chennault tried to modify the Chinese air force’s tactics. But the

pilots were undisciplined, poorly trained, and considered practicing

missions disgraceful. They also refused to take orders from a foreigner.

Crashes were common and any pilot who survived training was licensed,

regardless of skill. Chennault found himself unable to make a

difference. By 1940, the Chinese air force had almost ceased to exist.

Many pilots were dead and the already obsolete aircraft had been

destroyed. When the Japanese pushed the Chinese government to the

western city of Kumming, with only the Burma Road, through the mountains

of northern Burma, remaining as a supply route, Madame Chiang sent

Chennault home to solicit airplanes and pilots to try to save the

country.

Chennault’s mission was successful for although the country was still

neutral, President Franklin Roosevelt wanted to help China, believing it

had the potential to become a great democracy. Through the Lend-Lease

program, China received Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks, powerful low-altitude

fighters. And the government looked the other way as recruiters went

onto military bases, looking for pilots and ground personnel.

Many

of the recruits of the AVG resembled the undisciplined band of

adventurers, barnstormers, and mercenaries that Chennault had feared the

project would attract. They lied about their flying experience, claiming

pursuit experience when they had flown only bombers and sometimes much

less powerful airplanes. The salary lured some--$500 a month plus $400

per confirmed kill bonus--nearly double the average military pilot

salary. Some joined to gain combat flying experience, others for the

adventure. During the summer of 1941, 300 men posing as tourists and

carrying passports that identified them as teachers boarded boats for

Asia.

The

AVG arrived at an English airfield in Rangoon, Burma, and began what

Chennault called "kindergarten," learning to fly fast, single-engine

fighters. Classes in Asian geography, the history of Japanese-Chinese

relations, and pursuit flying tactics adapted to the P-40 supplemented

flight training.

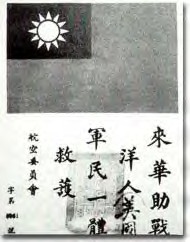

Flying Tiger banner presented to

the Army Air Force by the Chinese government during World War II.

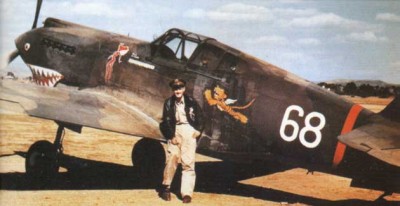

By

November 1941, the pilots were trained and most of the P-40s had arrived

in Asia. The volunteers adopted shark’s teeth, which they had seen in a

magazine photograph of English P-40s in North Africa, as their squadron

symbol, and they painted it on all the AVG planes. The men didn’t know

that their stateside administrative office had already chosen the

nickname "Flying Tigers" for the group and had contracted Walt Disney

Studios to design a logo. Although the flyers initially scoffed at the

name and logo, they eventually wore it with pride, along with the

shark’s teeth.

The large embroidered patch worn

on the back of a Flying Tiger's leather jacket. The Chinese flag and

script identify the flyers, should they be shot down and captured. This

precluded their execution as spies or guerillas

At the

end of their training, the Flying Tigers were divided into three

squadrons: the Adam and Eves, the Panda, and the Hell’s Angels, and

assigned to opposite ends of the Burma Road. One rotating squadron was

stationed with the RAF in Rangoon and two were sent to Kumming. On

December 20,1941, the Kumming units entered their first battle, where

they shot down six Japanese planes. On Christmas Day, the Rangoon

squadron had its first victories. The victories began adding up, but the

small unit was unable to slow the massive Japanese advance.

Repairing a Flying Tiger P-40 at

Kunming, China.

On

February 28, 1942, after two days of intensive fighting during which the

Pandas claimed 43 victories, Rangoon fell to the Japanese. There were

only six airplanes left to evacuate to Kumming; the rest were grounded

for lack of spare parts. Then, on March 20, Japan attacked an RAF base

in Burma. The attack wiped out the RAF in Burma and the Hell’s Angels

was reduced to four flyable planes. As revenge, Chennault sent ten

planes with his best pilots to attack the Japanese air base in Chiang

Mai, Thailand. The mission destroyed more than 30 planes on the ground

with a loss of only two P-40s.

Combat

wasn’t as easy as the recruiters had promised. The Japanese greatly

outnumbered the Flying Tigers. They flew sorties nearly every day, with

no replacement pilots and few spare parts for the planes. Many

contracted tropical diseases. By March, the men were exhausted. And they

began noticing more U.S. army officers in Kunming. The fiercely

independent pilots began to worry that the AVG would soon be inducted

into the U.S. Army Air Force. None wanted to return to the military with

its rules and disciplined lifestyle. Pilots and mechanics began to

resign.

At the

same time, the Flying Tigers were becoming heroes back home. Americans

needed to feel they were doing something to avenge Pearl Harbour. Along

with Jimmy Doolittle’s bombing raid on Tokyo, the Flying Tigers became

the symbol of U.S. military might in Asia. It was not surprising that

the USAAF wanted to absorb the unit when the China-Burma-India Theatre

was organized under the command of Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell.

Stilwell was already using the AVG for strafing and low-level

reconnaissance missions. The missions were useless, but the soldiers on

the ground loved to see friendly planes attacking the enemy. But among

the pilots who risked their lives, morale plummeted. Finally on April

18, Chennault received orders for a bombing mission to Chiang Mai. The

AVG pilots revolted, saying they had joined to fight the Japanese, not

to cheer up Allied soldiers. A deal was struck and the mission was

aborted, but on May 8, it became irrelevant. The Japanese captured the

Burma Road. Supplies for China now had to be flown in from India on a

route called "the Hump."

With

no mission, the AVG began to disband. The Army Air Forces wanted to

induct the group into the 14th Air Force. Chennault received a

commission in April 1942, and the remaining AVG members were asked to

join. Many had already resigned, others wanted to go home, and the navy

veterans in the group wanted to serve with the navy, not the army. When

the AVG was dissolved into the 23rd Fighter Group on July 4, 1942, only

five members remained. The 23rd inherited the name, which it still

carries today. It is estimated that 85 percent of the AVG veterans

returned to duty with the U.S. armed forces. The American Volunteer

Group ended its career with an estimated 300 victories.

Chennault stayed in China after the war, running an airline that was

sold to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency after he died in 1958. It

became Air America, a covert air force used in the early days of the

Vietnam War.

In

1991, the Department of Veterans Affairs credited AVG service as time

served with the U.S. armed services. The pilots were awarded the

Distinguished Flying Cross, and the technicians and staff were given the

Bronze Star. After almost half a century, the first Americans to fight

the Japanese were finally being recognized. They were mercenaries,

gamblers, idealists, bar brawlers, and adventurers; but most

importantly, the men of the AVG were patriots.