|

helicopter development in the early 20th century

Paul

Cornu in his first helicopter in 1907. Note that he is sitting between the

two rotors,

which rotated in opposite directions to cancel torque.

This helicopter was the first flying machine to have risen from the ground

using rotor blades instead of wings.

At the end of the nineteenth century,

the internal combustion engine became available, making the development of

full-sized vertical-flight craft with adequate power a possibility.

However, other problems remained, particularly those relating to torque,

dissymmetry of lift, and control. Inventors during the next two decades

built many small prototype helicopters that attempted to solve these

problems, but progress came only in small steps.

Gaetano A. Crocco of Italy patented an

early cyclic pitch design in 1906. Crocco recognized that a way to change

the pitch cyclically on the blades was needed if a helicopter was to work

properly in forward flight.

During 1906, the brothers Louis and

Jacques Bréguet began their helicopter experiments and meticulously tested

airfoil shapes under the guidance of Professor Charles Richet. In 1907,

they built the Bréguet-Richet Gyroplane No. 1, one of the first mechanical

devices to actually hover. The gyroplane flew

for one minute on August 24, 1907 (some sources say September 29, 1907) in

what is generally accepted as the first vertical flight. A

45-horsepower (33.5-kilowatt) engine provided just enough power to achieve

vertical flight. However, there was no means of control or stability, and

it needed four men to steady it while it hovered

about 2 feet (0.6 meters) off the ground.

Without a control system, it was not a practical helicopter.

Louis

Breguet, one of the foremost helicopter pioneers, built the first

full-scale helicopter

to leave the ground with a pilot in 1907. However, it had no means of

control

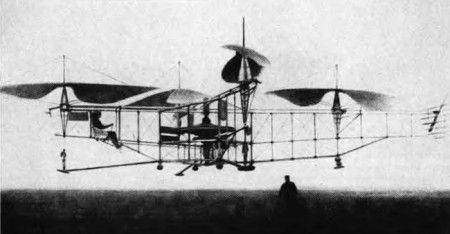

On November

13, 1907, the French bicycle maker Paul Cornu became the first person to

rise vertically in powered free flight.

His helicopter used two counter-rotating rotors to cancel torque.

Some control was achieved by placing auxiliary paddle-like wings below the

rotors, and sticks held by men on the ground stabilized the machine.

Although Cornu achieved a historic first,

rising about one foot (0.6 meter) and hovering for about 20 seconds, the

controls were inadequate, and the craft never developed into a practical

helicopter.

In

1907, the French inventor Paul Cornu made a helicopter that used two

20-foot (6-meter)

counter-rotating rotors driven by a 24-hp (18-kW) Antoinette engine.

It lifted its inventor to about five feet (1.5 meters) and remained aloft

one minute.

In June 1909, Igor Sikorsky built his

first helicopter, the S-1, in Kiev, Russia. The wooden craft weighed 450

pounds (204 kilograms) and had dual coaxial rotors. But the two blades

were inefficient, and the most powerful engine that was available, a

25-horsepower (20 kilowatt) Anzani engine, could not lift its own weight.

The next year, he built the S-2, which weighed only 400 pounds (181

kilograms) and had a three-blade rotor system. This model could rise, but

the engine was too weak to carry a passenger. The machine also shook and

vibrated violently because it needed a stiffer frame. Sikorsky turned to

airplane development, returning to helicopters only in the 1930s after he

emigrated to the United States.

The first vertical flight machine in the

United States seems to have been developed by Emile Berliner and John

Newton Williams. Berliner designed what may have been the first production

rotary aircraft engine, the 36-horsepower (27-kilowatt) Adams-Farwell

engine. In 1908, Williams constructed a coaxial machine for Berliner using

two of these engines. It reportedly lifted both Williams and the machine—a

weight of 610 pounds (277 kilograms)—but was probably steadied from the

ground. Williams later built another craft using a 40-horsepower

(30-kilowatt) Curtiss engine. It hovered at around three feet (0.9 meter),

again steadied from the ground. Berliner also was the first to propose the

auxiliary vertically mounted tail rotor.

The

Berliner 1921 single-wing rotary-powered helicopter had deflector vanes at

the wing tips.

Handicapped by a heavy 80-hp engine, this early coaxial helicopter built

by Emile Berliner

along with J. Newton Williams, lifted its own weight into the air in 1908.

This helicopter used skid landing gear.

Emile's son, Henry, later designed another craft that flew with some

success carrying a pilot in 1924.

Professor Zhukovskii and his students at

Moscow University may also have constructed a primitive coaxial helicopter

in 1910. Zhukovskii was well known for his theoretical contributions to

aerodynamics and published several papers on the subject of rotating wings

and helicopters.

In 1912, the Russian Boris Yuriev built

a 445-pound (202-kilogram) helicopter that had a modern-looking single

rotor and smaller tail rotor and large diameter, high aspect ratio blades.

The tail rotor was needed to counteract the torque generated by the main

rotor but it added weight and like Sikorsky's helicopters, had an

undersized engine. The machine never flew properly. But Yuriev was one of

the first to use a tail rotor and also one of several pioneers to propose

the concept of cyclic pitch for rotor control.

Around 1912, the Danish aviation pioneer

Jacob Christian Ellehammer became interested in vertical flight. He

designed a coaxial helicopter with counter-rotating rotors that were

stacked vertically. Each rotor consisted of a large aluminium ring about 20

feet (six meters) in diameter with six five-foot (1.5-meter) blades

attached to the outside edge of the rotors. A cyclic pitch mechanism was

used to change the pitch of the rotating blades and for control.

Ellehammer made several short hops in the craft.

This

helicopter, with two superimposed airscrews rotating in opposite

directions,

was built by J.C.H. Ellehammer in Denmark in 1912. It flew but never rose

above four feet.

Two Austrians, Stephan Petroczy and

Professor Theodore von Karman, built and flew a coaxial rotor helicopter

during the closing years of World War I. Intended for observation, this

machine included a pilot/observer position above the wooden

counter-rotating rotors, inflated bags for landing gear, and a

quick-opening parachute. Three 120-horsepower (89-kilowatt) rotary engines

provided power. The machine achieved numerous short vertical flights

restrained by cables and reached a height of more than 150 feet (46

meters).

Around 1919, Henry Berliner built a

counter-rotating coaxial rotor machine that made brief uncontrolled hops

to a height of about four feet (1.2 meters) while steadied from the

ground. In 1922, he mounted two coaxial counter-rotating rotors on the

wing tips of a Nieuport biplane fuselage. Sets of movable vanes—flat

surfaces mounted under the rotors—provided some control. The craft

reportedly could manoeuvre in all directions and obtained a speed of about

40 miles per hour (64 kilometres per hour). In June 1922, it hovered

around 12 feet (3.3 meters) off the ground and was successfully

demonstrated to the U.S. Army in 1924. The Berliner aircraft are

considered the first rudimentary piloted helicopters developed in the

United States.

During the late 1910s and early 1920s,

Louis Brennan of England's Royal Aircraft Establishment worked on a

helicopter with an exceptionally large two-bladed rotor. To deal with the

problem of torque, Brennan used a single rotor and mounted propellers on

the blades themselves. The use of servo-flaps or ailerons inboard of the

propellers achieved control. He took several low-altitude flights, which

ended in October 1925, when the machine crashed.

In the 1920s, the Marquis Raul Pateras

Pescara, an Argentinean working in Europe, achieved one of the first

successful applications of cyclic pitch. He was also the first to

demonstrate that a helicopter with engine failure could still reach the

ground safely by means of autorotation—the phenomenon that caused blades

to turn even without power being applied to them that resulted from the

flow of air as the craft moved through it. His coaxial helicopter had

biplane-type rotors with a total of 20 lifting surfaces. In 1924, Pescara

set a new world record by flying his craft almost one-half mile (0.8

kilometre) in 4 minutes and 11 seconds—a speed of about eight miles per

hour (13 kilometres per hour)—at a height of six feet (1.8 meters).

This

helicopter, designed by George De Bothezat and Ivan Jerome,

made its first public flight on December 18, 1922, at McCook Field near

Dayton, Ohio.

A Russian immigrant to the United

States, George de Bothezat, designed and built a four-rotor machine

powered by a 180-horsepower (134-kilowatt) rotary engine under the

sponsorship of the U.S. Army.

It weighed 3,600 pounds (1,633 kilograms),

and the x-shaped structure was more than 60 feet (18.3 meters) wide, with

four huge fan-shaped rotors mounted at each corner. The pilot controlled

individual collective pitch mechanisms for each rotor. De Bothezat flew

the helicopter on its first flight at McCook Field near Dayton, Ohio, in

October 1922. This flight lasted about a minute and a half as the craft

rose six feet (1.8 meters), drifted with the wind, and landed some 500

feet (152 meters) away. Over the next two years, the helicopter made more

than 100 test flights—some rising to 15 feet (4.6 meters) and one with

three passengers clinging to the frame to demonstrate the machine's

stability. The U.S. Army tested the machine and commented favourably on it.

But the Army abandoned it because of its complexity and unreliability and

because de Bothezat was difficult to work with.

This

helicopter, built by Etiénne Oehmichen, had four lifting airscrews

and five auxiliary propellers.

It set flight records in 1924.

Another French pioneer, Etienne

Oehmichen, began his experiments in 1920 by suspending a balloon above a

twin-rotor helicopter to provide additional lift. A later design had four

lifting airscrews and five auxiliary propellers. On April 14, 1924, he

flew this type of craft, powered by a 180-horsepower (134-kilowatt) Rhone

engine, 1,181 feet (360 meters), establishing the first helicopter

distance record officially recognized by the Federation Aeronautique

Internationale. On May 4, he was the first to fly a helicopter at least

one kilometre (0.6 mile) in a closed circuit in a 5,550-foot

(1.692-kilometer) flight that lasted 14 minutes and rose to 50 feet (15

meters).

|