|

Ornithopters,

Helicopters and Kites

As the dream of flight lurched toward reality

during the nineteenth century, two

developments begun centuries

earlier came to a climax. One was the failure of

attempts to create an

ornithopter—a flying machine that emulated

birds by having flapping wings—and its cousin, the

helicopter, and the other was the development of the

kite, which had been around in

some form or other for

centuries.

In most minds, Italian theorist Giovanni Alfonso

Borelli had laid the

ornithopter question to rest, yet

doubts persisted. New findings about bird flight were

casting doubt on Borelli’s

conclusions, and new engineering techniques and designs were

keeping the possibility of

human-powered winged flight alive. One widely

publicized plan was that of

Frenchman Jean Pierre Blanchard,

who later achieved fame as a balloonist. His machine

consisted of an enclosed cabin in which a man’s

pedalling with both arms and legs

would be amplified by gears and

transferred to the flapping wings outside.

In 1809, it was widely reported

that the Austrian Jacob

Degen had successfully flown in an

ornithopter. In fact, the reports

and the illustrations that

accompanied them neglected to

mention that Degen and his

contraption, an embellishment of

Besnier’s design, were tethered

to a large hot-air balloon.

Degen actually used his wings

to provide him just enough lift

to rise with the help of the

balloon. In this manner, he

went balloon-jumping in large

leaps on a parade ground, to the

delight of onlookers, but only the

most gullible would take

that for flying.

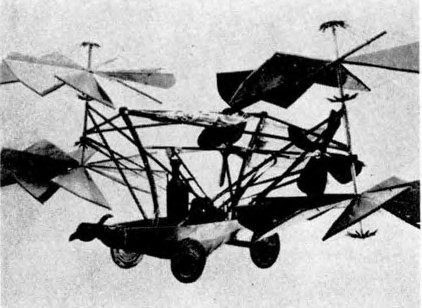

Front and aerial views of Jacob Degen’s flying machine as

it appeared in the early nineteenth century,

but with one important element missing: the

huge balloon that actually carried Degen aloft.

Still, Degen had made a contribution: unlike

Blanchard and others, his design

was actually built

and offered some approximation

of flight. It also spurred public

interest in flight—Degen performed

his “act” before appreciative

crowds in Paris and Vienna

sporadically from 1806 to

1817. Most importantly,

however, reports of Degen’s

“flight” prompted Sir George

Cayley to publish in 1809 the

first of his monumental three-part treatise, On

Aerial Navigation, a landmark

in the history of flight.

In 1810, Thomas Walker’s

somewhat more practical design

for an ornithopter of

Thomas Walker appeared. Though

streamlined and mindful of

streamlined and mindful of weight limitations, the craft had

no chance of ever being airborne. Some elements of its

design, however, caught the eye of experimenters in

heavier-than-air flight. Although enough experimental and

theoretical findings were published throughout the century

to show that ornithopters were never going to be feasible

flying machines, and the foundation for the airplane had

already been laid early in the century, the 1800s saw an

ever increasing number of ornithopter designs, particularly

from American inventors.

The reason for this was an

odd policy of the U.S. Patent Office that granted a large

number of patents for such devices; this policy existed

because of an assumption that heavier-than-air flight was

impossible. (European patent offices were more careful, thus

discouraging a great many crackpot designs.) Inventors from

weekend tinkerers to Thomas Edison offered a bewildering

array of designs, and many were granted patents—but none of

these machines flew. A close relative of the ornithopter,

the helicopter—a device in which blades rotate in a

horizontal plane lifting the device—did see some success in

the nineteenth century. As early as 1784, two Frenchmen,

Launoy and Bienvenu, built a primitive helicopter powered by

a tightly wound cord. Similar success was achieved by

Vittorio Sarti in 1828, and by W. H. Phillips in 1842, both

of whom used a steam engine as a power plant.

These

machines had no mechanism for control and were less

manoeuvrable than balloons. Yet experimenters sensed that

this, like the airplane, was an area of great potential.

Meanwhile, an age-old device known for centuries, the kite,

also underwent some serious study and development. Kites had

been used in China since several centuries before Christ,

and Marco Polo reported in the fourteenth century that the Chinese

had developed kites powerful

enough to carry a man aloft. The

artistry of Chinese kites has been

dazzling through the centuries,

and their introduction into Europe

by sailors and merchants who brought them back from the

Orient delighted

both adults and children.

But the development of the kite

into a device of interest to

aeronautical researchers was

the work of a remarkable Australian, Lawrence

Hargrave, one of the many

extraordinary figures in the early

history of flight about whom very little is known.

From 1850 to 1915, Hargrave

worked in New South Wales,

Australia, on many aspects of flight. Far

removed from aeronautical

activity in Europe and America, and

with only a rudimentary grasp of

mathematics and physical science, he was a

first-class draftsman and mechanic.

In 1887, he invented the

rotary engine that was later to

become a standard design for aircraft power plants,

and in 1893 he created the

box kite, which was of even more

immediate importance.

In 1899, Hargrave

attended a meeting of the

Aeronautical Society in London and delivered a paper on the

box kite. It was immediately obvious

to all the attendees, as it had been to Hargrave,

that the box kite design was

highly adaptable to gliders and eventually to airplanes.

Among those who attended was Percy

Pilcher, who was later to achieve fame as a glider

pilot using Hargrave’s box

kite design. In fact, the designs of

early European—but not American—aircraft show the

profound influence of Hargrave. The box kite design

was eventually abandoned when it

was realized that the

configuration sacrificed too much manoeuvrability to

aircraft stability (and as

with the Wrights later, whom Hargrave

resembled in many ways, stubborn adherence to

principle prevented Hargrave from

adapting to new forms, limiting

his contribution to aviation history).

Early Helicopter Technology

Helicopter flight was probably the first

type of flight envisioned by man. The idea dates back to ancient China,

where children played with homemade tops of slightly twisted feathers

attached to the end of a stick. They would rapidly spin the stick between

their hands to generate lift and then release the top into free flight.

In the western world, the ancient Greek

mathematician, physicist, and inventor, Archimedes, who lived and worked

in the second century B.C.E. perfected the principle of the rotating screw

for use as a water pump. When the screw was rotated inside a cylinder, the

screw moved the water in front of it. At the same time, the water resisted

and pushed back. This resistance also applied to the movement of screws

through air—a type of fluid.

The 15th century Italian

Leonardo da Vinci has often been cited as the first person who conceived

of a helicopter capable of lifting a person and then experimented with

models of his designs. His sketch of the "aerial-screw" or "air gyroscope"

showed a device with a helical rotor. The helical surface on his device

resembled a helicopter and was made from iron wire and covered with linen

surfaces made "airtight with starch."

In

1483, Leonardo da Vinci of Italy sketched the most advanced plans of the

period for an aircraft that was really a helicopter.

His theory for "compressing" the air to obtain lift was substantially

similar to that of the modern helicopter.

Leonardo planned to use muscle power to

revolve the rotor, although such power would never have been sufficient to

operate a helicopter successfully. His notes implied that his models flew,

but from his sketch, there was no way to deal with the torque created by

the propeller. Although he had undoubtedly identified the concept of a

rotary-wing aircraft, the technology needed to create a helicopter had not

yet been produced. His drawings date to 1483, but they were first

published nearly three centuries later.

A large number of fanciful inventions

surfaced between the time of Leonardo and the 20th century.

These helped advance the knowledge of vertical flight, but they all lacked

sufficient power to achieve flight and were too bulky and heavy. Serious

efforts to create a real helicopter did not occur until the early years of

the 20th century.

In 1754, Mikhail Lomonosov, the "Father

of Russian Science," suggested that a coaxial rotor machine could be used

to lift meteorological instruments. He developed a small coaxial rotor

modelled after the Chinese top, but powered by a wound-up spring that he

demonstrated to the Russian Academy of Sciences in July 1754. The device

may have climbed and flown freely or it may have been suspended from a

string.

J.P. Paucton seems to have been the

first European to propose the helicopter as a man-carrying vehicle. In his

Theorie de la vis d'Archimedes, he described a man-powered machine

called a Pterophere with two airscrews—one to support the machine in

flight and the second to provide forward propulsion.

In 1783, the French naturalist Launoy,

with the assistance of his mechanic Bienvenu, used a version of the

Chinese top in a model consisting of two sets of rotors made of turkey

feathers that rotated in opposite directions. This "counter-rotation"

solved the problem of torque since the forces created by each rotor

cancelled each other out. They demonstrated the model, which resembled

Lomonosov's model in principle, in 1784 before the French Academy of

Sciences and succeeded in achieving free flight.

Launoy

and Bienvenu designed a version of the Chinese top that consisted of two

sets of rotors

made of turkey feathers that rotated in opposite directions, which solved

the problem of torque.

George Cayley, who, as a young

boy, had been fascinated by the Chinese top, built his earliest

vertical-flight model, a twin-rotor helicopter model in 1792 and described

it in On Aerial Navigation in 1796. It was very similar to Launoy

and Beinvenu's model. By the end of the 18th century, he had constructed

several successful vertical-flight models with rotors made of sheets of

tin and driven by wound-up clock springs. In a scientific paper published

in 1843, Cayley described a relatively large vertical flight aircraft

design that he called an Aerial Carriage. However, his device remained

only an idea because the only engines available at the time were steam

engines, which were much too heavy for successful flight.

In

1843, Sir George Cayley of Great Britain drew up plans for this "aerial

carriage"

that used rotors on opposite sides to counteract torque. This

configuration is sometimes still used.

The lack of a suitable engine stifled

aeronautical progress, but the use of miniature lightweight steam engines

met with limited success. In 1842, the Englishman W.H. Phillips

constructed a steam-driven vertical flight machine that ejected steam

generated by a miniature boiler out of its blade tips. Although

impractical to build at full-scale, Phillips' machine marked the first

time that a model helicopter had flown powered by an engine rather than by

stored energy devices such as wound-up springs. He exhibited his model at

the Crystal Palace in London in 1868.

Another idea at this time, documented by

Octave Chanute in Progress in Flying Machines, was a model built by

Cossus of France in 1845. It had three rotating aerial screws that were

moved by steam power. Chanute also mentioned a device by a Mr. Bright that

consisted of axles that were suspended beneath a balloon and rotated in

opposite directions.

This

1845 design for a primitive helicopter by Cossus appeared in Octave

Chanute's Progress in Flying Machines.

The rotating screws were to be moved by steam power.

A U.S. Confederate soldier, William

Powers, designed an attack helicopter in 1862 that made use of Archimedes'

screws powered by a steam engine that was to propel it vertically and

forward. He intended to use it to break the Union's siege of the southern

ports. He constructed a non-flying model but did not construct a full-size

craft.

In France, an association was set up to

assemble the many helicopter models and designs that had proliferated

during the 1860s. In 1863, the Vicomte Gustave Ponton d'Amecourt built a

model helicopter with counter-rotating propellers and a steam engine. He

patented it in France and Great Britain and exhibited it at the 1868

London Aeronautical Exposition. This machine failed, but another model

using spring propulsion had better luck. He called his machines "helicopteres,"

which was derived from the Greek adjective "elikoeioas," meaning spiral or

winding and the noun "pteron," meaning feather or wing.

Gustave

Ponton D'Amecourt constructed, in 1865, an aerial screw machine that

worked by steam.

It was exhibited at the London Aeronautical Exposition in 1868.

In 1870, Alphonse Penaud constructed

several model helicoptére that he fashioned after the Chinese top. They

had two superimposed screws rotating in opposite directions and set in

motion by the force of twisted rubber bands. Some of his models rose to

more than 50 feet (15 meters). In 1871, Pomes and De la Pauze designed an

apparatus that had a rotor powered by gunpowder, but it was never built.

Penaud's flying screw, which the French called a "Helicoptere," consisted

of two superimposed screws

rotating in opposite directions and powered by the force of twisted rubber

bands.

This design inspired by the Wright brothers when they were boys.

In 1877, Emmanuel Dieuaide, a former

secretary of the French Aeronautical Society, designed a helicopter with

counter-rotating rotors. The engine boiler was on the ground and connected

to the machine by a flexible tube. Also that year, Melikoff designed and

patented a helicopter with a conical-shaped rotor that doubled as a

parachute for descent.

The

invention of Dieuaide, at one time secretary of the French Aeronautical

Society,

consisted of two pairs of square vanes set a various angles to the line of

motion so as to

vary the pitch and rotated in opposite directions by gearing. It had a

steam engine.

In 1878, Castel, a Frenchman, designed

and built a helicopter driven by compressed air with eight rotors on two

counter-rotating shafts. This model did not work, but a smaller one built

by Dandrieux between 1878 and 1879 and driven by elastic bands did.

Also in 1878, Enrico Forlanini, an

Italian civil engineer, built another type of flying steam-driven

helicopter model powered by a 7.7-pound (3.5-kilogram) engine. This model

had two counter-rotating rotors and rose more than 40 feet (12 meters),

flying for as much as 20 seconds.

This

design by Melikoff in 1877 consisted of a screw parachute.

It would be rotated by a gas turbine. It was designed to carry a man.

In the 1880s, Thomas Alva Edison

experimented with small helicopter models in the United States. He tested

several rotor configurations driven by a gun cotton engine, an early form

of internal combustion engine. However, a series of explosions that blew

up part of his laboratory deterred him. Later, Edison used an electric

motor for power, and he was one of the first to realize from his

experiments that a large-diameter rotor with low blade area was needed to

give good hovering efficiency. Edison's scientific approach to the

problems of vertical flight proved that both high aerodynamic efficiency

of the rotor and high power from an engine were required for successful

vertical flight.

At the end of the nineteenth century,

inventors had not solved the inherent aerodynamic and mechanical

complexities of building a vertical flight aircraft. The hundreds of

failed helicopter inventions had either inadequate power or control or

experienced excessive vibration. Some of the better-designed early

helicopters managed to hop briefly into the air, but they did not attain

sustained flight with control. Steam engines were just too heavy for a

full-scale helicopter. Not until the internal combustion engine was

invented and became available could inventors develop full-sized models.

A number of technical problems

challenged the early developers of helicopters. These included limited

knowledge of the aerodynamics of vertical flight, the lack of a suitable

engine, the inability to keep the weight of the structure and engine low

enough, the problem of excessive vibration, the inability to deal with the

torque created by the propellers, and the inability to achieve adequate

stability and control.

|