|

ancient flying myths and

legends

The

history of flight is the history

of a dream:-human-kind’s dream to

soar through the sky like a bird.

Birds

seem to fly with so little effort

that it was only natural

that early attempts to fly

would be attempts do emulate

birds. Early myths about

flight and probably many

early attempts involved

fashioning wings out of birds'

feathers. Since ancient

times, however, it was suspected

that the mechanism of bird flight

was more complicated

than it appeared to the

naked eye.

Although a clear

understanding of bird

flight was not attained until the

twentieth century, the

issue was considered settled with

the posthumous publication

in 1680 of Giovanni Alfonso

Borelli’s De Motu Animalum.

Borelli described bird flight

(erroneously, as it turned

out) as the combined effect of

the action of the

individual feathers as they twist

and turn

during flight and the complex

flapping of the wings,

and claimed to prove that

human musculature was far

too weak to support a

system of this kind.

Yet, birds are not the only

creatures that fly. Bats,

insects, and even some

species of fish, fly without the

complex structures of

feathered wings, and virtually

everyone has witnessed leaves,

feathers, seeds, and what-not

floating gently to the earth or

being borne up by a

gust of wind. It was also

clear that heated air had the

ability to carry things

aloft, a phenomenon often

observed in ovens and kilns

throughout the Middle Ages.

And even birds are often

observed to be kept aloft with

out flapping their wings,

not unlike the kite, a toy known

since ancient times. It was

just a short leap of imagination

to envision a larger

version of these flying objects

with a

person aboard.

And imagination was in no short

supply

as intrepid (or perhaps foolhardy)

would-be aeronauts

constructed and tested a wide

variety of flying machines, often

resulting in death or injury as

they plummeted to earth. Yet, of

the more than fifty documented

instances of attempts to fly

before 1800 that historian Clive

Hart lists in his beautiful book,

The Prehistory of Flight, about a

dozen may have been brief

instances of legitimate flight or

gliding. One such attempt—by

Besnier, a locksmith from Sable,

France—involving a pair of

wood-and-taffeta wings worn on the

back and flapped by ropes attached

to the hands and feet, became a

celebrated instance of flight. And

while there was always some doubt

about Besnier’s claims, believing

them to be true only spurred the

resolve of later experimenters.

Borelli’s findings, and the many

disastrous failures to “fly like a

bird,” soon made it apparent that

the entire matter of human flight

would have to be rethought if

there was to be any progress.

Several scientific findings of the

seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries laid the foundations for

the science of flight: an

appreciation of the fact that the

air that surrounds us is a fluid

and that it may exert forces in

particular ways under the right

conditions; that the forces

required for flight can be

separated, first conceptually and

then practically; the development

of the propeller as a by-product

of the study of windmills and

waterwheels by John Smeaton and

the British engineers

of the eighteenth century.

Amazingly, the theory of the

airplane may be said to have been

born by 1799—more than a century

before the Wright brothers’

achievements at Kitty Hawk—in the

work of Sir George Cayley, an

English baronet who worked on the

problem from the 1790s until his

death in 1857. Cayley understood

the basic principles of flight and

constructed working models,

perhaps even one that carried a

human being aloft, and for this

reason he is known as “the father

of aeronautics.” But Cayley had a

long tradition on which to build,

and in many ways his genius lay in

being able to bring together

well-established science with the

legends and dreams of flight.

While the foundations of

heavier-than-air flight were being

laid, lighter-than-air flight was

progressing through the late

1700s. The Montgolfier brothers

(one of many brother teams to be

found throughout the history of

aviation) made their historic

flight in 1783, and the balloon

soon found a successful military

application when it was used by

the French at the Battle of

Fleurus to defeat the Austrians.

As thrilling as balloon flight

was, its main contribution was to

whet the appetite of the

aerialists for real controlled

flight, a dream that would not be

realized for a century.

The

French balloon L’Entrepenant

helps direct the French

forces against the Austrians

in the Battle of Fleurus,

June 26,

1794. Messages are passed

between the observers and

the ground by the anchoring

ropes.

Ancient Myths

Nearly all ancient

cultures contain myths about flying

deities. The gods of ancient Egypt, Minoa, and

Mesopotamia were often depicted as having magnificent

wings, and the Persian god of gods, Ahura Mazda, is

depicted in the Palace of Darius I at Susa (about 490

B.c.) as being nearly all wings.

The ancient Hebrews had traditions of placing wings on the

seraphim and on the cherubim that were on the Ark of the

Covenant, but neither they nor the

ancient Greeks and Romans saw

wings as an absolute necessity for

flight. Greek gods flew without any visible means and biblical

descriptions of angels (such as

those who visited Abraham or the one who wrestled with Jacob) are

not depicted as winged.

Wings on angels were not to become standard, in

fact, until well into the Middle

Ages. To the people of ancient

civilizations, flying was the

province of the gods; humankind’s place was on earth. For a human to don wings was an expression of the desire to

become closer to the divine, but it was also seen

as arrogant, a mere mortal’s attempt to usurp a prerogative

of the gods. Two ancient myths demonstrate this ambivalence

to flight: the tale of the Persian king Kai Kawus, who was

said to have ruled around 1500 B.C., and the story of King

Bladud of Britain (the supposed father of Shakespeare’s King

Lear), who is supposed to have ruled about 850 B.C.

Winged flight was considered the province of the gods for most cultures, as illustrated

by this relief (from the temple of Susa in ancient Babylonia) depicting winged sphinxes and the winged disc, emblem of the god Ahura Mazda.

According to a fable contained in the Book of Kings, -

composed by the poet Ferdowsi in A.D. 1000, king Kai Kawus

was tempted by evil spirits to invade heaven with the help

of a flying craft. This craft consisted of a throne to the

corners of which were attached four long poles pointing

upward. Pieces of meat were placed at the top of; each pole

and ravenous eagles were chained to the feet. As the eagles

attempted to fly up to the meat, they carried the throne

aloft. Inevitably, however, the eagles grew tired and

the throne came crashing down.

In Persian literature, Kai Kawus is known as “The Foolish King” (even though the legend

has the eagle-propelled craft flying the king all the way to

China). King Bladud’s motivation for attempting to fly seems

to have been somewhat different: he was promoting magic and

wizardry (and, perhaps, ingenuity) in the kingdom. Legend

has it that the king donned large wings made of feathers and

took flight over the city of Trinavantum (present-day

London). As he twisted in the air, he lost his balance in

mid-flight and came crashing down into the Temple of Apollo,

in full view of his horrified subjects. Unlike Kai Kawus,

however, Bladud remained a popular, if tragic, figure in

British mythology.

The legend of

Kai Kawus, the Persian king who was taken aloft on a throne lifted by eagles, was a

favourite subject

of folklore, as in this 1710 manuscript, in spite of

the folly the king represented.

In China, there are many

legends of emperors flying in chariots or with

the use of wings. As early as 2200 B.C., the

emperor Shun is reported to have escaped a

burning tower and later to have flown over

his dominion with the aid of two large reed

hats. Such hats are still worn in areas of China

today and can be as much as three feet wide.

Shun may well have been the first parachutist in

history. Analogous figures can be found in the

mythology of nearly every ancient civilization.

In Northern Europe Wayland the Smith was carried

into the sky by a shirt made of feathers. In

Africa Kibaga the warrior flew invisibly over

his enemies and dropped rocks on them (the first

mention of the possibility of aerial

bombardment). He was finally killed when his

adversaries simply shot their arrows

blindly in the air. These fables were meant as

warnings that humans should not attempt to

penetrate the heavenly realms, literally

or figuratively. No doubt these cautionary

reminders fired

the imagination of as many people as they

intimidated.

Daedalus and Icarus

The Greek legend of

Daedalus and Icarus is no doubt

the most famous of the ancient legends of

flight. Many aspects of the

legend are worth considering since they

certainly influenced later

generations of experimenters. In

Greek mythology, Daedalus (Greek for “cunning artificer”) is

an unusual figure: an Athenian

architect and engineer with

near-godlike intellectual powers. He is

the mythical inventor of

the axe and the saw, and was said by

Plato to have constructed

mechanical statues of the gods

so lifelike that they perspired under the hot Aegean

sun and had

to be restrained lest they run away.

Daedalus also

invented various puzzles and gadgets that

amazed onlookers, including a box that

could be opened only by the

sound of birdsong in perfect

harmony. In

time, Daedalus moved to Crete with his son,

Icarus, and became the

resident architect and

inventor for the

wealthy King Minos. His greatest public

achievement was the

design and creation of the dreaded

Labyrinth, a maze

built in the city of Knossos and said to be

so cleverly

crafted that once one entered the maze it was

impossible to find

one’s way out. In the

center of the Labyrinth was

the monstrous Minotaur, who was half-bull

and half-man. Every

year Minos sacrificed fourteen Athenian

youths to this

creature. Being an Athenian himself, this

did not sit

well with Daedalus. He supported Theseus, King

of Attica, in his plot

to overthrow Minos and

shared with him the

secret to finding one’s way out of the

Labyrinth.

After Theseus

killed the Minotaur, set fire to the palace,

and escaped with the king’s daughter, Ariadne,

Daedalus’ disloyalty was

discovered and the king sent his soldiers to

arrest him. Years earlier

Daedalus had witnessed the witch Medea

take flight in a chariot drawn by fiery dragons;

since then, he had secretly

.devoted himself to creating a mechanism that would allow

him to fly. When he and Icarus

arrived at Crete, they had set up a secret workshop

in the cliffs overlooking the sea.

Daedalus spent many hours observing the silent gliding

flight of the eagles that nested in the cliffs; he then

experimented with many materials that might work for wings.

Sail canvas was too heavy, silk and thin cloth were too

weak. At last Daedalus came upon the obvious: why not

construct the wings out of eagle feathers? The inventor was

sad to be hunting the magnificent birds, but he soon

collected enough feathers to fashion wings with beeswax.

Daedalus was about to begin testing his invention when word

came that Minos’ men were coming to arrest him. He and

Icarus quickly repaired to their secret cliff-side workshop

and donned their untested wings.

Daedalus instructed his son to fly at a middle altitude—

high enough so that the ocean spray would not dampen the

wings and make them too heavy; low enough so that the heat

of the sun would not melt the wax that held the feathers

together. With that they took off across the Aegean Sea,

hoping to glide all the way to Sicily. The end of the story

is well known to most Westerners. Icarus, intoxicated

with the thrill of flying, flew too high. The wax melted,

his wings came apart, and he plunged to his death in the

sea, near an island that was later named Ikaria in his

honour. Crete does, in fact, have tall cliffs overlooking

the sea, against which strong and persistent thermal

updrafts are created by winds known as the Miltemi. Large

gulls (the eagles, if there ever were any, are long gone)

float and glide for long periods. Beginning with the

excavations of Sir Arthur Evans in 1900, many of the details

of the leg- end of King Minos and the Labyrinth have been

confirmed, bit by bit, and some historians (no less a figure

than H.G. Wells, for example) have come to believe that the

legend of Daedalus and Icarus has some basis in fact.

The Chinese and Their Rockets

Rocketry and space

exploration are often included in histories of aviation, but

there are only a few superficial

points the two enterprises share. In both cases, a

vehicle is used to transport a

person or cargo above the surface

of the earth. Sometimes vehicles that are

rocket-propelled may also be

airworthy, as in the case of the Space Shuttle.

The skills and physical abilities of

astronauts were, at least

in the early stages of space flight, determined to be

similar to those of test

pilots. And NASA, the U.S. government agency that is

responsible for the space program,

grew directly out of NACA, the agency responsible for

experimentation and research in

atmospheric flight. But

rocket flight is very different from aerial flight

(different even from jet-

propelled flight) and its place in the history

of aviation is mainly in the early stages, when the

distinction between the two was still blurred.

A rocket is simply a

device in which an object—the

payload—is propelled by the reactive effect of hot gasses

exhausted in a specific direction. The faster the gas is

spewed out in one direction, the heavier the payload can be

and the faster it can be propelled in the opposite

direction. The earliest rockets were almost certainly

Chinese—there is little doubt that the Chinese first

developed “black powder,” the basic propellant used in

rockets. The combination of salt-peter, charcoal, and

sulphur was probably used in fireworks by the Chinese

centuries before Christ lived, but the only written records

available are dated well into the Middle Ages. Mongols

besieging the city of Kaifeng in 1232 used arrows propelled

by rockets (though primarily as a psychological weapon).

Knowledge about rocketry seems to have moved with the Mongol

invasions—the Arabs are seen as having developed rockets by

the thirteenth century and are reported as having used them

against Saint Louis in the Seventh Crusade; the Italians

were experimenting with rockets by the fifteenth century. A

major refinement in the formula for black powder was made in

the thirteenth century by Roger Bacon; this resulted in the

creation of gunpowder.

The British encounter with rockets in India led William

Congreve to develop the Congreve rocket, the ancestor of the

modern ballistic missile. The British used Congreve rockets

during the War of 1812 (as “The Star-Spangled Banner”

reminds us), and at the Battle of Waterloo.

LEFT:

The ancient

Chinese had a means of making a rocket propelled

chair, as in this depiction of Emperor Wan-Ho

blasting off, but whether or not they actually

attempted this feat is uncertain!

RIGHT:

The military uses of rocket

power are depicted in this 15th century

illustration of a blunderbuss. Bellifortis

Manuscript

What is strangest about

rockets when considered from the perspective of aviation is

that, even though rockets were used extensively throughout

history all over the world—and soldiers in the field who

were exposed to rockets conjectured about what it might be

like to “ride” one or have one strapped to one’s

back—writers of fiction rarely used rockets as a means of

transportation when they created stories about trips to the

½ Moon or to outer space until well into the nineteenth

century.

Cyrano

de Bergerac’s L’Autre Monde (The Other World), completed in

1662, is a notable exception. In it, Cyrano is carried to

the Moon by a ship fitted with many rockets. But virtually

all other writers used every conceivable device—from geese

to cannons to spheres filled with dew—except rockets. Even

Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon, published in 1865,

has space travellers flying to outer space in a capsule shot

out of a cannon. This is why the remarkable 1881 drawings of

Nikolai Kilbalchich of a crewed platform propelled by a

battery of rockets, drawn literally moments before he was

led to his execution for plotting against Tsar Alexander II

(and thus not discovered until after the Russian Revolution

in 1917), or Konstantin Tsiolkolvski’s 1883 drawings

(published in 1903) of staged rockets with a crewed cockpit

in the nose, were so revolutionary. Somehow, rockets drew

people’s attention skyward but failed to inspire dreams of

flight until humankind looked to conquer the stars

themselves.

|

The Middle Ages

Roger Bacon

The first individual to write in what

we would consider a serious, scientific

way about the possibility

of flight was Roger Bacon, a

Franciscan monk who lived from

1214 to 1292. Bacon was a

prolific writer and devoted much energy to

defending the power of reason and to ridiculing

medieval scholasticism and the “magic

of alchemy. Those who

followed him look upon Bacon as a

critically important step in humankind’s emergence

from the ignorance of the Dark

Ages; considering he had little

support around him, he was probably one of the

keenest minds of

human history. In 1260,

Bacon wrote a work on the superiority of

reason called De Mirabili

Potestate Artis et Naturae (On the

Marvellous Powers of Art and Nature). In it he suggests that

human reason is so powerful that it could even

manage to do something that seems utterly

impossible, namely, build a

machine that would enable a person to

fly. The manuscript—which was not published for nearly three

hundred years—then yields two incredible passages.

The first

outlines two possible ways in which a person might fly. One

is a rough description of what was later to become known as

an ornithopter. The other is a more detailed description of

a globe filled with “ethereal air.” Having demonstrated that

air is a kind of fluid in which less dense objects might

float like a ship floats on water, Bacon suggests methods of

thinning the air in a globe that will give it buoyancy in

air—more than five hundred years before lighter-than-air

flight would become a reality. The second remarkable section

is even more intriguing, for in it Bacon claims, “There is

an an instrument to fly with, which I never saw, nor know

any man that hath seen it, but I full well know by

name the learned man who invented the same.”

It is possible

that Bacon is referring to his fellow Englishman, Eilmer

(also known as Oliver) of Malmesbury, a monk who was the

first of the so-called tower-jumpers—people who tried to fly

by jumping off a high place with winglike contraptions

connected to their arms or body. Most of these attempts

ended in the death of the jumper, but Eilmer, who jumped in

about 1010, some 250 years before Bacon, was reported to

have glided about 250 yards (228.5m) and survived a bumpy

landing (though he broke both his legs). Eilmer is

immortalized in a stained glass portrait in the Malmesbury

Abbey, holding his batlike wings (perhaps pre-flight, since

he is standing rather erect). If Bacon meant a device used

in his own day that flew successfully, it was certainly the

best kept secret of the Middle Ages.

|

Leonardo

da Vinci:Forgotten

Genius

It is not possible to write a history of

aviation without mentioning

Leonardo da Vinci, the Italian

artist and scientist who lived and worked in Florence in the

late fifteenth century, even though

fate dictated that he would

have virtually no impact whatever on the development of

flight. In spite of his

brilliance, the world knew nothing

of his theoretical work in aviation for the simple reason

that nearly none of his notes were published (or even known

about) until the late 1800s. Unlike Bacon, whose influence

lay mainly in his efforts to dispel the human fear of flying

as an impossible or demonic activity, Leonardo was very

secretive about his aviation research, committing his

drawings and notes to paper in a mirror writing that would

conceal his findings from most observers.

Leonardo discussed some

things with his contemporaries (not many, since that could

some times prove dangerous for a man like him), but it does

not seem that anyone had any idea of his aeronautical

musings. In all, Leonardo left behind a large body of work

about flight: more than five hundred sketches and

thirty-five thousand words. Much of his work involved the

careful study of birds and of batlike wing sections. He

realized that human physiology was not capable of birdlike

flight, but he designed many ornithopters that required

coordinated pedalling of arms and feet. Most of his

conclusions about how birds fly were wrong, and these errors

rendered most of his aircraft useless. Recent models based

on Leonardo’s drawings have been built and flown for very

short distances, but it is unlikely that the builders will

be marketing kits very soon. Two aspects of Leonardo’s work

are interesting, though.

First, he did realize that

an aircraft would require a tail section to stabilize the

flight. And, second, he conceived of a proto-helicopter that

used a wide screw to lift itself into the air. The principle

behind this device, the Archimedean screw, was known since

antiquity and was used to transport water uphill or up from

a well. Leonardo seems to have been the first to apply the

mechanism to aviation. Here, too, however, the power was to

be provided by a human being, making it a hopeless

enterprise. Of his many designs, da Vinci made only one

model: a miniature version of his helicopter. After he

constructed the model, he wondered (in his notes) whether

the machine would have to wait for the invention of a

lighter power source than a human being to work. That no one

tried anything remotely like any of the designs contained in

his notebooks in the century after he died is evidence of

how private this work was.

Leonardo

da Vinci spent some forty

years—his entire adult

life—working on the problem of flight. His approach was to

emulate birds, and

these drawings reveal his

careful anatomical studies

of birds’ wings

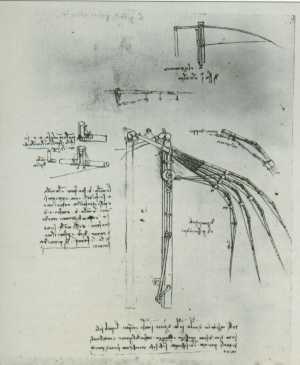

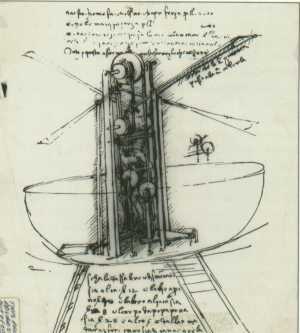

Da

Vinci’s genius is also apparent in

his plan for a

four-wing ornithopter that

maximizes human muscle output,

enabling the operator

to mechanically flap wings via

gears and pulleys.

None of these drawings was

known to anyone working on

flight until the late

eighteenth

century

|

|

|