|

the Beginning of Transatlantic Services

Boeing 377 Stratocruiser

There are perhaps no

air routes more travelled and more important in the Western world than

those connecting the United States and Europe. Since the advent of

commercial air travel after World War I, airline entrepreneurs had been

exploring the possibility of flying transatlantic routes. To conquer

the Atlantic was to link Europe and the Americas, the two great

industrial centres of the world. While the limitations of aviation

technology of the 1920s made commercial transatlantic air travel

prohibitive, the historic flight of Charles Lindbergh in 1927 excited

the imagination of many who dared to dream of regular flights across

the vast expanse of ocean.

The North Atlantic presented major challenges for aviators due to

unpredictable weather and the huge distances involved coupled with the

lack of intermediate stopping points. Initial commercial forays into

transatlantic services, therefore, focused more on the South Atlantic,

where a number of French, German, and Italian airlines offered seaplane

service for mail between South America and West Africa in the 1930s.

German airlines, such as Deutsche Luft Hansa, experimented with a

number of mail routes over the North Atlantic in the early 1930s, both

with seaplanes and with dirigibles, but these were not regularly

scheduled services and never led to commercial operations. There were,

however, hundreds of transatlantic crossings with passengers made by

zeppelins during the late 1920s and 1930s, including probably the most

famous zeppelin of all, the luxurious Graf Zeppelin.

Other airlines such as the British Imperial Airways and Pan American

Airways began working toward experimental transatlantic flights only in

1936, partly because the British were unwilling to grant landing rights

for American air carriers until then. Both airlines decided to use

flying boats because concrete runways were rare at coastal airports on

the Atlantic, and also because landplanes capable of flying such

distances without refuelling simply did not exist at the time. Both

airlines carried mail rather than passengers in the early years. An

average flight from coast to coast, using the Short S.23 Empire flying

boats, took nearly a day.

Coast-to-coast flights using the Short S.23 Empire flying boats took

almost a day Pan

American, under the leadership of the charismatic Juan Trippe, was one

of the pioneers of commercial transatlantic service. Trippe recognized

early that one major hurdle to regular transatlantic travel would be

political. He was instrumental in negotiating agreements with several

countries for landing rights at intermediate points in the Atlantic

such as Newfoundland, Greenland, the Azores, and Bermuda. Based on the

results of early exploratory flights, Trippe concluded that the most

efficient route across the Atlantic would be the northern route, via

the north-eastern coast of Canada, past Greenland, via Iceland, and

then into northern Europe.

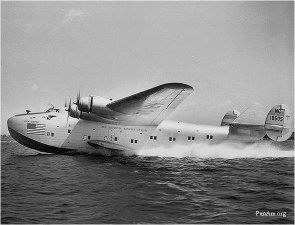

On December 9, 1937, Pan American invited bids from eight U.S. airplane

manufacturers to build a 100-seat long-range airliner. Boeing, which

won the competition, offered its legendary B-314 flying boat. Probably

the finest flying boat ever produced and the largest commercial plane

to fly until the advent of the jumbo jets 30 years later, the

double-decker B-314 had a range of 3,500 miles (5,633 kilometres) and

could carry as many as 74 passengers. Each plane cost more than half a

million dollars.

After a well-publicized dedication ceremony, attended by First Lady

Eleanor Roosevelt, on March 26, 1939, the Pan American B-314 Yankee

Clipper made its first trial flight across the mid-Atlantic, from

Baltimore, Maryland, all the way to Foynes in Ireland. The airline

began regular mail services with the B-314 in May 1939; scheduled

flight time was about 29 hours. With increased confidence in its new

plane, Pan American finally inaugurated the world's first transatlantic

passenger service on June 28, 1939, between New York and Marseilles,

France, and on July 8 between New York and Southampton. Passengers paid

$375 for a one-way trip across the ocean. By the beginning of World War

II, Pan American, with its considerable experience in Pacific and South

American operations with the famous Clipper service, dominated the

transatlantic routes. The airline offered regular flights with its

seaplanes from La Guardia airport in New York City to Lisbon in

Portugal, which was the most common entry point into Europe at the

time.

Pan Am's Yankee Clipper made its first flight across the mid-Atlantic

on March 26, 1939

Commercial services during World War II

were intermittent at best. Pan American also conceded some of its

monopoly to the British Overseas Aircraft Corporation (BOAC), which had

purchased three B-314s for its own transatlantic service, just before

the beginning of the war. The major turning point in transatlantic air

service occurred in June 1945 when the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board

granted permission to three airlines to operate service across the

North Atlantic. They were American Export Airlines, Pan American, and

Transcontinental & Western Airlines (TWA). This agreement finally broke

Pan American's monopoly over international air travel and contributed

to the flourishing of air travel in the post-war era. (American Export

would merge with American Airlines on November 10, 1945, to become

American Overseas Airlines (AOA).

American Export became the world's first airline to offer regularly

scheduled landplane (as opposed to seaplane) commercial flights across

the North Atlantic. Using the reliable DC-4 aircraft, it began

passenger services from New York to Hurn Airport near Bournemouth in

England (with stops at Gander, Newfoundland, and Shannon, Ireland) in

October 1945. Each one-way flight lasted about 14 hours. Pan American

debuted its own flights a few days later also using the DC-4.

Eventually, the company began using the new Lockheed Constellation and

Super Constellation aircraft, both of which had pressurized cabins that

allowed them to fly as high as 20,000 feet (6,096 meters). In August

1947, Pan American opened a new era by beginning regularly scheduled

non-stop flights between New York and London using these aircraft.

Transatlantic air travel in the immediate post-war years remained a

novelty, but it offered significant advantages over sea travel. A usual

journey by sea across the Atlantic took about five days, while air

travel cut that down to less about half a day. Events in the post-war

era also led to a rise in commercial cooperation between Western

European countries and the United States, which increased tourism and

made air travel easier. European airlines were in too weak a position,

however, to take advantage of the new demand for transatlantic

passenger travel because of their post-war equipment and aircraft

shortage. Here, American air carriers, such as Pan American, AOA, and

the relative newcomer TWA were able to fill the new needs. TWA joined

Pan American and AOA in offering regularly scheduled transatlantic

services in February 1946 using the Constellation, and quickly became a

stiff competitor to the two other U.S. air carriers.

The history of commercial transatlantic air travel underlines how both

political factors (international permits and civil aviation acts) and

technological frontiers (the advent of the Boeing B-314) were key

factors in the expansion of commercial air travel.

While American air services dominated transatlantic routes at the end

of World War II, eventually European carriers began to take advantage

of the growing market. By the end of the 1940s, Scandinavian Airlines

System (SAS), the Royal Dutch Airlines (KLM), Air France, the Belgian

SABENA, and Swissair all were carrying passengers across the Atlantic

as part of a new post-war air travel boom. Where ten years previously,

the transatlantic route was a rarely travelled passenger route, by

1950, it had become the world's number one route in terms of traffic

and produced high revenue and fierce competition among some ten major

international airlines. The Atlantic had finally been conquered for the

common passenger. |