|

to the stratosphere

Over the years, balloonists, or aeronauts, have attempted to fly farther,

higher, and longer. The British Charles Green, along with Thomas Monck

Mason of Ireland and British Robert Hollond, were some of the first

aeronauts to set a record when, in November 1836, they flew The Great

Balloon of Nassau almost 500 miles (800 kilometres) from London,

England, to Weilburg, Germany, in 18 hours. Interestingly, they landed in

exactly the same spot that

Jean Pierre Blanchard had landed on his 1785 balloon flight.

During the nineteenth century, balloonists had blazed a trail into the

upper air, sometimes with tragic results. In 1862 Henry

Coxwell and James Glaisher almost died at 30,000 feet (9,144 meters).

Sivel and Crocé-Spinelli, who ascended in the balloon Zénith in

April 1875 with balloonist Gaston Tissandier, died from oxygen

deprivation. The last men of the era of the nineteenth century to dare

altitudes over 30,000 feet (9,144 meters) were Herr Berson and Professor

Süring of the Prussian Meteorological Institute, who ascended to 35,500

feet (10,820 meters) in 1901, a record that stood until 1931.

The

first men to reach 30,000 feet (9,144 meters) did not know what they were

facing. It is now known that at an altitude of only 10,000 feet (3,048

meters), the brain loses 10 percent of the oxygen it needs and judgment

begins to falter. At 18,000 feet (5,486 feet), there is a 30 percent

decrease in oxygen to the brain, and a person can lose consciousness in 30

minutes. At 30,000 feet (9,144 meters), loss of consciousness occurs in

less than a minute without extra oxygen.

In

1927, aeronaut Captain Hawthorne C. Gray, of the U.S. Army Air Corps,

ventured into the

stratosphere. He set a U.S. altitude record at 29,000 feet (8,839

meters) on his first flight, and although he attained 42,000 feet (13,222

meters) on his second flight, it was not an official record, because he

had to parachute out of his balloon as it descended to save himself. His

balloon, Army No. S-30-241, was a 70,000-cubic-foot (1,982-cubic-meter)

single-ply rubberized silk envelope coated with aluminium paint. Gray's

three flights offered him the opportunity to test high-altitude clothing,

oxygen systems, and instruments as well as set a new record. On his third

flight in November 1927, he reached 42,000 feet (13,222 meters) again, but

ran out of oxygen on the descent. He arrived on the ground with his

balloon, but he was dead. It was the last high-altitude flight in an open

basket until 1955, when these types of projects were reinstated to develop

pressure and spacesuits.

Gray 's death underscored the central problem facing high-altitude

balloonists—somewhere between 40,000 and 50,000 feet (12,192 and 15,240

meters), the air pressure becomes so reduced that a person's lungs cannot

function and gases begin to bubble out of the blood. To fly above 40,000

feet (12,192 meters) without a pressure garment or the protection of a

pressurized vessel was to invite death.

The

1930s saw a large number of flights into the stratosphere.

Auguste Piccard led the efforts. He had an absolute faith that science

could solve anything, and he considered the problem of oxygen deprivation

to be no obstacle. A leading cosmic ray investigator, he needed to rise

above the atmosphere to study it. Obviously, he would have to design a

sealed, pressurized gondola.

Using an apparatus developed by the Germans for use in submarines during

World War I, Piccard built a gondola sphere 82 inches (208 centimetres) in

diameter that weighed 300 pounds (136 kilograms). The gondola was designed

to keep two people alive for up to 10 hours above 40,000 feet (12,192

meters). The apparatus released pure oxygen into the cabin while scrubbing

and re-circulating cabin air by filtering it through alkali.

Piccard also solved the problem of the lifting gas of the balloon leaking

away as it expanded during ascent by using a balloon envelope five times

larger than necessary to get off the ground. The lifting gas would remain

inside the balloon envelope as it expanded, giving him enough lift to

return safely to Earth as the gas cooled at night. His 500,000-cubic-foot

(1,416-cubic-meter) gas bag, fully inflated, could have lifted a

locomotive.

On

May 27, 1931, Piccard and Paul Kipfer climbed into the stratosphere in a

spherical, airtight, metal cabin suspended from a specially constructed,

hydrogen-filled balloon. This balloon, with a capacity of 494,400 cubic

feet (14,000 cubic meters), reached an altitude of 51,783 feet (15,787

meters). The following year Piccard ascended to an even higher 53,152 feet

(16,200 meters) with Max Cosyns.

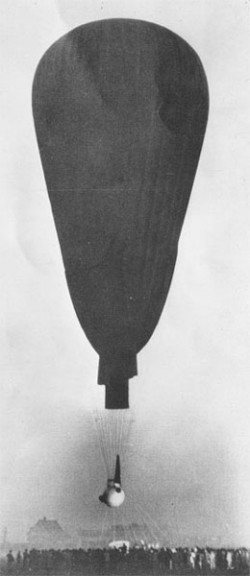

Auguste Piccard and Paul Kipfer take off in 1931

on a record-setting flight

Inspired by Piccard's success, the Soviet Union flew the largest balloon

built to date, at 860,000 cubic feet (25,353 cubic meters), with a

gondola. The balloon reached a record 60,700 feet (18,501 meters) on Sept.

30, 1933.

Not

to be outdone, the United States flew the Century of Progress,

whose team was headed by Auguste Piccard's twin brother

Jean Piccard, with a gondola to a record height of 61,000 feet (18,592

meters) on November 20, 1933. The balloon carried two instruments to

measure how gas conducted cosmic rays, a cosmic ray telescope, a

polariscope to study the polarization of light at high altitudes, fruit

flies to study genetic mutations for the U.S. Department of Agriculture,

and an infrared camera to study the ozone layer.

The first flight of the Century of Progress,

August 1933

The

next year on January 30, 1934, a Soviet balloon flew to 72,000 feet

(21,946 meters), but it descended too quickly and the crew died.

In

1934, the U.S. Army Air Corps again began to participate in high-altitude

flights. Captain Albert W. Stevens piloted the Explorer I and

Explorer II. Explorer I had a balloon of 3,000,000 cubic feet

(84,950 cubic meters), five times the volume of the Century of Progress.

The first flight of Explorer I climbed to 60,613 feet (18,475

meters) on July 27, 1934, but the balloon ripped. and Stevens, co-pilot

Maj. William Ellsworth Kepner, and Orvil A. Anderson, operations officer,

had to parachute to safety.

Explorer I during its ascent to 60,613 feet on

July 28, 1934

Explorer I falling after its gas bag ruptured

Later that year, Jean Piccard and his wife,

Jeannette Piccard, flew the refurbished Century of Progress

safely to 58,000 feet (17,678 meters). As the first woman to fly to the

sub-stratosphere, Jeannette Piccard received a lot of publicity. Some

organizations felt that a mother should not be taking such risks. When she

was asked if she was afraid, she replied, "Even if one were afraid to die,

there is so much of interest in a stratosphere trip that one does not have

time to be afraid. It is too absorbing, too interesting."

In

June 1935, a Soviet mission climbed to 52,800 feet (16,093 meters) in a

balloon. This was the first of many flights taken by the Soviets to

systematically explore the upper atmosphere, emphasizing physics over

records.

Explorer II was the last high-altitude flight of the 1930s. It had an

envelope of 3,700,000 cubic feet (104,772 cubic meters) and was the first

helium balloon. Its sealed gondola kept the crew from freezing to death

and their blood from boiling due to the low air pressure. On November 10,

1935, Explorer II reached 72,395 feet (22,066 meters), high enough

to see the curvature of the Earth. Piloted by Anderson and Stevens, it set

a world altitude record that would stand for the next 21 years.

Their flight marked the end of the great era of human stratosphere

ballooning. The enormous and heavy balloon envelopes had clearly reached

the limits of rubberized fabric balloon technology, and a worldwide

depression was setting in. At the cost of additional lives, the absolute

ceiling between 40,000 and 50,000 feet (12,192 and 15,240 meters), where

life could no longer be sustained, had been breached, paving the way for

the next wave of exploration.

|