|

airships and balloons in World War Two

The U.S. Navy began

acquiring non-rigid airships toward the end of the 1920s. The first

non-rigid airship it acquired was an unusual airship because it was

metal-clad. Built by the Aircraft Development Corporation, the ZMC-2 was

the only metal-clad airship built. It was delivered to the Navy on

September 12, 1929, and saw experimental use and use on various

humanitarian missions. Although it was somewhat hard to control during

rough air, it remained in service for 12 years. When it was scrapped, its

airtime had exceeded 2,200 hours.

During the 1930s, the

Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company built a fleet of non-rigid airships, or

blimps, that it was using for advertising and barnstorming. The U.S. Navy

took advantage of Goodyear's expertise and hired Goodyear to build its new

airships. The first airship was the prototype K-1. Goodyear built the

envelope (the balloon), and the Naval Aircraft Factory built the control

car that hung below the envelope.

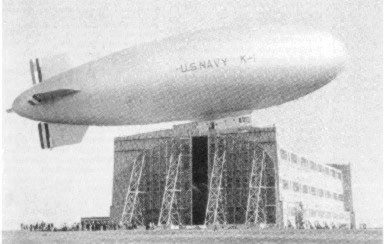

A K-type blimp landing at Lakehurst Naval Air Station, New Jersey.

This airship burned a new

type of fuel gas that resembled propane rather than the standard liquid

fuel. This fuel had some interesting properties. It could be contained in

cells within the airship envelope and, since it had approximately the same

density as air, the buoyancy of the airship did not change as the fuel was

burned. This kept the airship steady. It also was more efficient than

liquid gasoline and eliminated the need to compensate for the weight of

the fuel that burned during flight.

The K-1 was an experimental airship and the first type to have the control

car suspended inside the envelope

Testing of the K-1 began

on October 7, 1931, at Naval Air Station (NAS) Lakehurst in New Jersey.

She was the largest non-rigid airship the Navy had operated up to that

time. She performed moderately well and was used until September 1940.

Following the K-1, the

Navy began to purchase both the blimp envelope and the control car from

Goodyear. The first blimp was the Defender, which the Navy

purchased in 1935 and designated the G-1. She was lost in a midair

collision with another airship on June 8, 1942, and 12 people died in the

crash.

The Navy went on to

purchase additional G-type airships, followed by L-type airships in 1937.

The Navy used both for training and utility work. During World War II,

these airships were flown primarily from the Naval Air Station at Moffett

Field, California and from Lakehurst in New Jersey.

L-class airships on a training flight near Naval

Air Station Moffett Field, California, in February 1944

During this period, the

Navy

airships

Akron

and Macon had both been lost—the Akron in 1933 and the

Macon in 1935. Consequently, the Navy stopped building rigid

airships completely and devoted more resources to non-rigid airships,

which were less expensive to build and operate than the rigid ships. The

Navy also took over jurisdiction for the airship program from the U.S.

Army Air Corps in 1937, which had shared responsibility for airships with

the Navy. The Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey, was designated

the centre of operations.

The Navy began expanding

its fleet, and the K-type airship became the backbone of the Navy's

airships program. The K-2 debuted on December 6, 1938, at the Goodyear

facility in Akron, Ohio, and Goodyear delivered it to the Navy on December

16. At the time, she was the largest non-rigid airship in the Navy's

inventory, with a capacity of 404,000 cubic feet (11,440 cubic meters).

She became the prototype for the wartime K-series.

After the attack on Pearl

Harbour in 1941, the Navy asked the U.S. Congress for authorization to

purchase an increased number of airships. By June 1942, Congress had

authorized the construction of 200 airships, and during the war, Goodyear

built a total of 168. At its production peak, the company was turning out

11 airships monthly.

The later K series

airships were slightly larger and had a capacity of 416,000 to 425,000

cubic feet (11,780 to 12,035 cubic meters). They were 253 feet (76 meters)

long, and 60 feet (18 meters) in diameter, and were powered by two

425-horsepower (317-kilowatt) engines that gave a top speed of 50 miles

per hour (80 kilometres per hour). They were not fast, but unlike an

airplane that could remain airborne for only a few hours, a K-ship could

stay aloft for 60 hours.

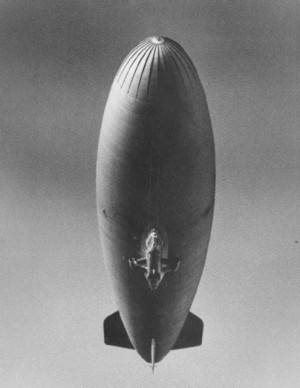

A K-ship on patrol. Note the depth bombs on the

underside of the control car

The United States was the

only power to use airships during World War II, and the airships played a

small but important role. The Navy used them for minesweeping, search and

rescue, photographic reconnaissance, scouting, escorting convoys, and

antisubmarine patrols. Airships accompanied many ocean-going ships, both

military and civilian. Of the 89,000 ships escorted by airships during the

war, not one was lost to enemy action.

The Navy airships

patrolled an area of over three million square miles (7.8 million square

kilometres) over the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and the Mediterranean Sea

during the war. They could look down on the ocean surface and spot a

rising submarine and radio its position to the convoy's surface ships. The

Navy's blimps initially operated from bases on the east and west coasts of

the United States, the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and as far south as

Brazil. Later in the war, they also operated from bases at Cuers, France,

and Pisa, Italy. In 1944, six K-ships flew across the Atlantic Ocean to

Morocco, where they established a low-altitude antisubmarine barrier

across the Strait of Gibraltar.

Only one airship was lost

to enemy action. A surfaced German Uboat shot down the airship K-74

during a battle, but the K74 damaged the German submarine so badly that

it could not submerge and was sunk by British bombers in the North Sea

while it was en route to Germany for repairs.

Both the Allies and Japan

also used balloons during World War II. The Allies used barrage balloons

(small blimps) to suspend aerial cables in the sky and foul enemy bombers.

A World War II Japanese balloon bomb. Japan

released more than 9,000 bomb-bearing balloons beginning on November 3,

1944. It is estimated that nearly 1,000 reached North America.

From November 3, 1944 to

April 1945, the Japanese launched 9,000 balloons carrying small 33-pound

(15-kilogram) incendiary bombs over the Pacific Ocean in the hope that the

winds would carry them to the United States. These were called the Fu-Go

Weapon, and supposedly were a revenge bomb for the 1942 Doolittle raids on

Tokyo. It is estimated that nearly 1,000 bomb-bearing balloons reached

North America, landing in 16 U.S. States, Alaska, Canada, and Mexico. The

last one found in North America was in Alaska in 1955—its payload still

lethal. It was picked up by a 74th Air Rescue Squadron H-5

helicopter crew from Ladd Air Force Base near Fairbanks, Alaska.

Only six Americans were

known to have died from balloon bombs. On May 5, 1945, a balloon bomb

exploded and killed Elsie Mitchell and five children near Lakeview,

Oregon. Although these bombs were psychologically effective, the U.S.

press didn't publish news of them to prevent the Japanese from learning of

the effect they had on the American people.

After 1945, the Navy

continued to use helium blimps in antisubmarine warfare, intermediate

search missions, and early warning missions. Some were equipped with

extraordinarily large airborne radar sets for early offshore warning of

bomber attacks against the United States. Two of the largest airships were

the ZPG-2 at 324 feet (99 meters) in length and a capacity of 875,000

cubic feet (24,777 cubic meters) and the ZPG-3 at 403 feet (121 meters)

long and a capacity of 1,516,000 cubic feet (43,000 cubic meters)--the

largest blimp type ever built. An airship of this type could stay aloft

without refuelling for more than 200 hours.

On August 31, 1962, the

Navy ended its use of blimps. In the 1980s, the Navy looked once more at

reviving airships, but Congress terminated funding for the project in

1989.

|