|

Military balloons 1850 - 1900

In

the nineteenth century, the military used balloons for three purposes. One

was for aerial bombing of military targets. The second was for aerial

reconnaissance by captive balloons. The third was for communications and

to transport personnel, mail, and equipment.

The

first aerial bombing was attempted in 1849 when the Austrians launched 200

pilotless, bomb-carrying hot-air balloons against forces defending Venice.

Each bomb was released by a time fuse. However, the wind sent the balloons

back over the Austrian troops. This idea was abandoned until the Japanese

revived it in World War II.

In

France and Austria, there was a brief attempt to use air-filled balloons (Montgolfiéres)

during the Italian campaign of 1859, but the results were unsuccessful

because the balloons would not stay aloft long enough.

Improved versions of balloons were used for bombing in various colonial

military campaigns, such as in the French capture of Dien Bien Phu near

the Vietnam-Laos border in 1884. In the early twentieth century, the

Japanese used balloons against Russian forces in Manchuria in 1904-1905,

as did the Italians in Tripoli in 1911-1912. This use of balloons for

bombing by the Japanese and Italians violated the 1899 Hague Peace

Conference that banned the "discharge of any ...explosive from balloons."

The

wartime use of balloons for bombing continued into modern times. Zeppelins

were effectively used during World War I. During World War II, the

Japanese turned the balloon into the first intercontinental strategic

weapons delivery system when they sent about 9,000 hydrogen-filled

balloons to the West Coast of the United States.

The

second use of balloons by the military was for aerial reconnaissance,

which began during the Napoleonic Wars. The U.S. military first used

balloons during the American Civil War.

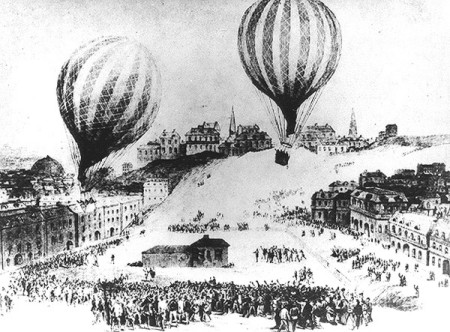

Night departure of a balloon during the Siege of

Paris, 1870

Possibly the most dramatic use of balloons in the war in Europe took place

in September 1870 during the siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War.

When Paris became completely surrounded by the Prussians, French aeronauts

suggested to the head of the Post Office that balloons should be used to

communicate with the outside world and with the provisional government at

Tours. The Post Office accepted the suggestion, and on September 23, the

professional aeronaut Jules Durouf departed from the Place St. Pierre in

Montmartre in Le Neptune with 227 pounds (103 kilograms) of mail.

He landed his balloon safely three hours and fifteen minutes later behind

enemy lines at the Chateau de Craconville. On his way, Durouf dropped

visiting cards on the enemy position as he flew above the reach of enemy

guns.

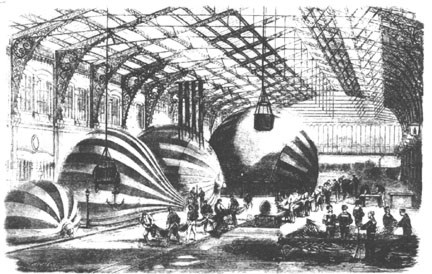

During the Siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian

War, 1870-1871, balloons were manufactured within railroad stations in

Paris. The balloons were used to get mail and passengers out of Paris

Due

to the direction of the winds and the fact that balloons could not really

be steered, the stream of balloons went in only one direction—out of

Paris. So, a later balloon, La Ville de Florence, transported

carrier pigeons as well as mail. The pigeons were used by the French to

carry messages back into Paris.

Since the balloons did not make their way back to Paris, the French needed

more and more balloons and began a flurry of balloon building. These new

balloons were built with cheap materials and were often piloted by

inexperienced aeronauts. Originating from the temporarily empty railroad

stations and yards, they ferried people, as well as mail and pigeons out

of Paris. Some were barely able to reach a safe landing away from enemy

lines. On October 7, 1870, the minister of the new French government, Léon

Gambetta, made a dramatic escape from Paris by balloon, and with his chief

assistant, Charles Louis de Saulces de Freycinet, established a

provisional capital in the city of Tours.

Because the Prussians were reputed to have a special anti-aircraft gun,

the French authorities ruled that, starting in mid-November 1870, balloons

must leave Paris only by night. This added new hazards for the

inexperienced aeronauts. Balloons could not be controlled, and they landed

at unexpected locations, sometimes with fatal results when they landed in

enemy territory. On one flight, two aeronauts became lost and drifted 800

miles (1,287 kilometres) to Norway. Two other balloons were lost without a

trace.

Altogether, a total of 66 balloons left Paris during the siege, and 58

landed safely. They carried some 102 people, more than 500 pigeons, and

five dogs, which were supposed to return to Paris carrying microfilm but

who never reappeared. The balloons also delivered more than two million

pieces of mail as far away as Tours, 125 miles (201 kilometres) to the

southwest of Paris.

The

war contributions of the aeronauts led to the formation, in 1874, of a

"Commission des Communications Aeriennnes." On its recommendation, a

military aeronautical establishment was set up in 1877 under the direction

of Charles and Paul Renard. This organization has continued to exist into

modern times.

Other countries followed France's example. Germany organized a Balloon

Corps in 1884, and Austria followed in 1893. Russia soon opened a school

for aeronautical training near St. Petersburg.

In

Great Britain, two officers, Captain F. Beaumont, who had served with

Thaddeus Lowe's Balloon Corps in the American Civil War, and Captain G.E.

Grover tried unsuccessfully to persuade the British military to recognize

the military value of balloons. But the first British military balloon was

not used until Captain J.L.B. Templer, an amateur aeronaut, brought his

own balloon, the Crusader, to Woolwich Arsenal in 1879 along with

another balloon, the Pioneer. The British began military balloon

training in 1880. Members of the balloon corps were trained in free flight

as well as in observations from a tethered balloon in case the tethered

balloon broke away from its cables. Templer almost died in one of these

free flights when the weather deteriorated, and a Member of Parliament who

was on the flight did die.

During this time, Templer and his associates realized that a new way of

storing the hydrogen gas that filled the balloons was needed because

generating the gas near the battlefield was too cumbersome and slow.

Compressed cylinders for the gas were suggested, and when the problem of a

gas-tight valve was solved, the cylinders came into use both in Britain

and in other countries. Storage pressures increased rapidly and, by 1890,

the French claimed they could inflate a small balloon in 15 minutes.

Templer also recognized the need for a lighter and more impervious balloon

fabric. He found a London family who had been using goldbeaters' skins

(the outer layer of the intestines of an ox used by goldsmiths) for toy

balloons and hired them to provide fabric to the British government. By

the end of 1883, they had produced their first balloon that could lift one

observer to a useful height. The balloon, the 10,000-cubic-foot

(283-cubic-meter) Heron, served in South Africa.

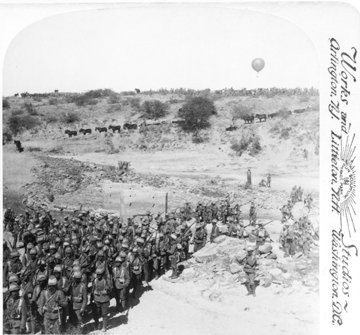

During the Boer War in South Africa, 1899-1902, a

balloon is used to watch for the Boers

The

advances in balloon technology impressed the British military, which moved

the Balloon Section to larger quarters and included it in British Army

establishments. They increased the number of balloon sections, and four

balloon sections participated in the South African War at the end of the

nineteenth century.

|