|

exploring other bodies

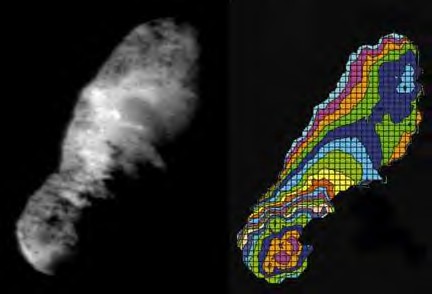

Comet Borrelly and its

topographical map (right) (Deep Space-1 mission).

The

planets were the first and most obvious targets for spacecraft

exploration. Once they had been visited, scientists turned some of their

attention to the smaller bodies of the Solar System, so-called

“planetesimals” including comets and asteroids. Most of this exploration

did not begin in earnest until the 1990s. But now the United States,

Europe, and Japan are devoting increased emphasis to these subjects,

because they offer clues to the formation of the Solar System.

There

are generally two categories of asteroids, those in the Asteroid Belt and

those classified as Near-Earth Objects, whose orbits cross Mars or even

Earth's path around the Sun and may pose a collision threat to Earth

itself. Both categories are similar in composition—either rocky or

metallic—and of interest to scientists. The Asteroid Belt is a region

between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Unlike in movies and television,

real asteroids are not bunched close together, constantly colliding with

each other, but spread far apart and one is not visible from another. Only

a few thousand are more than a kilometre in diameter.

Unlike

asteroids, comets are not rocky or metallic but primarily “dirty

snowballs,” are less dense than water, and travel in highly eccentric

orbits causing them to sweep into the inner Solar System and then back

out into deep space. As they get nearer the Sun (usually inside the orbit

of Saturn), their heat causes their surfaces to vaporize and fly off in a

long thin gaseous “tail.” They have thus been some of the most enigmatic

objects in the sky and have terrified observers for thousands of years.

Scientists have been particularly intrigued with them because they

represent some of the original building blocks of the Solar System and

because comets may be the source of Earth's water as well as its organic

matter.

The

first visit to an asteroid was made in October 1991, when NASA's space

probe Galileo flew past the asteroid 951 Gaspra on its way to Jupiter. In

August 1993 Galileo flew past another asteroid, 243 Ida. Galileo

discovered that Ida had a spherical 1.5-kilometer-wide satellite later

named Dactyl. Later, astronomers observing from the ground discovered that

the asteroid known as 4179 Toutatis was actually a double object. Because

of the discovery of Dactyl and Toutatis, planetary astronomers now believe

that asteroids with their own tiny satellites are common. Some scientists

even think that asteroids could have two or three tiny moons in orbit

around them, although none have been discovered so far.

This is the first full picture

showing both asteroid 243 Ida and its newly discovered moon

to be transmitted to Earth from the National Aeronautics and Space

Administration's (NASA's) Galileo spacecraft

--the first conclusive evidence that natural satellites of asteroids

exist.

The

second mission to fly by an asteroid was not as lucky as Galileo. The

small Department of Defence technology demonstration spacecraft Clementine

was built for the Ballistic Missile Defence Organization (BMDO) to test

advanced systems such as star tracking devices. It conducted a successful

lunar mapping mission and was headed toward asteroid 1620 Geographos in

1994 when it malfunctioned. It never reached its target.

The most

extensive asteroid mission was made by NASA's Near Earth Asteroid

Rendezvous (NEAR) spacecraft, which was launched in 1996. NEAR

successfully flew by the asteroid 253 Mathilde on its way to its primary

target, the asteroid Eros. The spacecraft eventually entered orbit around

Eros on February 14, 2000, becoming the first spacecraft to orbit around

an asteroid. NEAR took spectacular photographs of Eros for a year.

Although NEAR had no landing legs and was never intended to land,

controllers gradually lowered its orbit and it made a risky “soft-landing”

on Eros in February 2001. This was the first landing of a spacecraft on a

body other than the Moon, Earth, Venus, or Mars. The mission was

successfully ended on March 1, 2001.

Deep

Space-1 was a NASA technology demonstration spacecraft launched in October

1998, and intended to test a number of new technologies for planetary

exploration, such as an ion drive engine and solar panels equipped with

focusing lenses to provide more power. Despite its main mission, DS-1 also

managed to conduct some worthwhile science during its journey through the

Solar System. In July 1999, it flew past the asteroid 9969 Braille and in

September 2001, past the comet Borrelly. It was finally shut off in

December 2001, but the technology that it proved is now being incorporated

into many more planetary missions. Japan's Muses-C spacecraft will launch

in late 2002, rendezvous with asteroid 1998 SF36, and collect surface

samples to return to Earth.

During

the 1970s, comets were monitored by satellites in Earth orbit. The first

robotic spacecraft visit to a comet was made by the NASA spacecraft called

International Sun-Earth Explorer 3 (ISEE-3), originally designed to study

the interaction of the solar wind and the Earth's magnetic field. ISEE-3

was renamed the International Cometary Explorer (ICE) and sent to the

comet Giacobini-Zinner. It flew through the comet's tail in September

1985. It did not have a camera, however, but detected unexpected particle

and field events in the tail of the comet and studied the way that the

solar magnetic field draped over the comet nucleus.

Six

months later, a flotilla of five spacecraft reached the famous Halley's

comet, which made an ideal target because its orbit was accurately known

and countries could plan missions to visit it long in advance. The

spacecraft that visited Halley were the European Space Agency's Giotto,

Japan's Suisei and Sakigake, and the Soviet Vega 1 and 2. These spacecraft

were able to measure how much water and dust Halley was losing each hour

and collect impressive images of the tail and nucleus.

Comet Halley as taken with the

Halley Multicolour Camera on the ESA mission Giotto.

After

that flurry of activity surrounding Halley, there was a long drought

before the next comet flyby, but comets will soon come under intense study

by a number of spacecraft. The reasons include a change in scientific

priorities, improved technology, and cheaper planetary spacecraft built

and launched in much less time than before.

The NASA

spacecraft Stardust, launched in February 1999, will make three loops

around the sun and will spend 150 days collecting particles of

interstellar dust. But its ultimate goal is to pass through the tail of

comet Wild-2, collecting samples. It will collect these particles in a

wispy material known as an aerogel and return them to Earth in a re-entry

capsule. They will be carefully isolated and studied. (Another NASA

mission, named Genesis and launched in August 2000, will use the same

technique to return particles from the solar wind.)

The

Comet Nucleus Tour (CONTOUR) mission launched in July 2002. It will slowly

fly past comet Encke in November 2003 and comet Schwassmann-Wachmann-3 in

November 2003. It may also rendezvous with comet d'Arrest in 2008, or

another comet not yet discovered. Deep Impact will launch in January 2004

and rendezvous with comet Tempel 1 in July 2005. It will deploy a small

probe that will impact with the surface at high velocity, creating a huge

crater and blowing up a cloud of debris that can be analyzed and offering

a view below the surface.

A much

more ambitious European comet mission, known as Rosetta (because comets

are the Rosetta stones of the Solar System) is scheduled for a January

2003 launch atop an Ariane-5 rocket. Rosetta will pass several asteroids

and then study the comet 46P/Wirtanen for two years, deploying a rover to

its surface. In 1999, NASA cancelled a similar mission known as Deep Space

4/Champollion. But comets remain near the top of NASA's exploration list.

|