Project Mercury was

America's first human spaceflight program and the first

major undertaking of the newly created National

Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). It proved

that human spaceflight was possible.

A human spaceflight

program had been envisioned even before NASA was formally

established. The U.S. military and the National Advisory

Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), NASA's predecessor, had

debated the best approach to such a program soon after the

Soviet launch of Sputnik I on October 4, 1957. NACA

engineer H. Julian Allen, an expert on problems relating

to the exceedingly great heat generated by vehicles

travelling at high speeds, proposed using a missile to

launch a blunt-shaped spacecraft into orbit. The blunt

shape would dissipate heat and allow for safe re-entry into

the atmosphere. Another NACA engineer, Maxime Faget,

suggested using retrorockets that would slow the vehicle's

speed and cause it to leave orbit, re-enter the atmosphere,

and parachute to an ocean landing. By July 29, 1958, when

President Dwight Eisenhower signed the National

Aeronautics and Space Act that created NASA, a plan to

send humans into space was in place. Its objectives were

to place astronauts in space, test their reactions, and

return them safely to Earth.

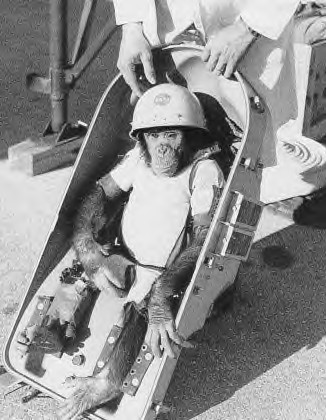

The chimpanzee Ham

was the live test subject for the Mercury Redstone 2

flight on January 31, 1961. Here the 17-kg (37-pound)

primate is fitted into a

special biopack couch prior to flight. The 680-kilometer

(420 statute miles)

suborbital mission was a significant accomplishment in the

American route to human spaceflight.

NASA was established on

October 1, 1958, and one week later, NASA formally created

Project Mercury. On December 17, exactly 55 years after

the Wright brothers' first flight, NASA's first

administrator, T. Keith Glennan, announced Project Mercury

to the public.

NASA promptly selected

the astronaut crew. Applicants had to be under 40 years of

age, shorter than 5 feet 11 inches (1.8 meters), in

excellent physical shape, and have a test pilot background

with at least 1,500 hours in the air. From an initial

pool of 508 candidates, NASA winnowed the number down,

finally subjecting 32 to an exhaustive and exhausting

array of physical and psychological tests before selecting

the “Mercury Seven.” Scott Carpenter, L. Gordon Cooper, Jr.,

John H. Glenn, Jr., Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, Walter M.

Schirra, Jr., Alan B. Shepard, Jr., and Donald K. "Deke"

Slayton were introduced to the public at a Washington,

D.C. press conference on April 9, 1959, and became instant

celebrities and heroes. As the authors of This New Ocean,

a history of Project Mercury, said: “The first seven

American astronauts were an admirable group of individuals

chosen to sit at the apex of a pyramid of human effort.…[They

became a team of personalities as well as a crew of

pilots. They were lionized by laymen and adored by youth

as heroes before their courage was truly tested.”

The greatest challenge to

Mercury engineers was to devise a vehicle that would

protect a human from the temperature extremes, vacuum, and

newly discovered radiation of space. Further, there was

the need to keep an astronaut cool during the burning,

high-speed re-entry through the atmosphere.

The spacecraft that was

designed was cone-shaped with a cylinder on top. It was

6.8 feet (2 meters) long, 6.2 feet (2 meters) in diameter,

and had a 19.2-foot, (5.8-meter) escape tower with a

solid-rocket motor fastened to the cylinder. In a launch

emergency, the rocket would fire and lift the capsule from

an explosion and parachute it into the ocean. With a

volume of only 428.5 cubic feet (12 cubic meters), there

was barely enough room for its pilot, who sat in a

custom-designed couch facing a panel with 120 controls, 55

electrical switches, 30 fuses, and 35 mechanical levers.

The cabin's atmospheric pressure was one-third of that on

Earth and contained pure oxygen.

The blunt end of the

capsule, which would enter the atmosphere first, was

covered with an ablative heat shield to protect it from

the 3000˚ F (1649˚ C) heat of re-entry into the atmosphere.

This shield would burn off and dissipate the heat during

re-entry and descent. Just before the spacecraft impacted

with Earth, the heat shield would detach from the base of

the capsule and release a balloon that would inflate to

cushion the landing. Parachutes would further slow the

descent.

The capsule's total

height, including its tower and the rockets attached to

the heat shield, was about 26 feet (8 meters). At launch

it weighed about 17,500 pounds (7,900 kg).

The program used two

different launch vehicles: Redstone rockets, designed by

the rocket team of Wernher von Braun in Huntsville,

Alabama, were used for the suborbital flights. Atlas-D

launch vehicles, modified ballistic missiles, launched the

orbital flights. The Atlas had such a thin skin (to save

weight) that it would have collapsed like a bag but for

its internal pressure.

Eighteen thrusters (small

rockets) operated manually by the astronaut controlled the

spacecraft's attitude (the way it was pointing). Three

retrorockets would fire the capsule out of its orbit and

begin its return to Earth.

Seven suborbital and four

orbital test flights preceded the piloted flights. On one

test flight, in January 1961, a surrogate “passenger,” a

chimpanzee named Ham, was put into a suborbital flight

that reached about 157 miles (253 kilometres) altitude.

Unfortunate Ham experienced much greater acceleration and

gravitational forces during the launch than expected.

Further, a leaky valve resulted in a severe drop in cabin

pressure. When the spacecraft finally splashed down 130

miles (209 kilometres) from its target area, the capsule

began to leak water. Ham survived, and the flight was

judged successful.

The first piloted Mercury

flight lifted off on May 5, 1961, with Alan Shepard behind

the controls of the Freedom 7. (Each astronaut named his

own spacecraft, and a “7” was added to honor the team.)

Reaching a speed of 5,146 miles per hour (8,282 kilometres

per hour) and an altitude of about 116 miles (187

kilometres), Shepard became the first American in space.

He descended safely as the Freedom 7 parachuted into the

Atlantic Ocean at the end of his flight. Although his

suborbital flight lasted only 15 minutes 22 seconds, it

proved that an astronaut could survive and work

comfortably in space, and demonstrated to the 45 million

Americans watching it on TV that the United States had

joined the spaceflight business.

Attempted recovery

of the Mercury capsule at the end of the second Mercury

mission, July 27, 1961.

In July 1961, Virgil

Grissom's flight in the Liberty Bell 7 resembled Shepard's

until splashdown when its emergency escape hatch

unexpectedly blew off. The capsule flooded and Grissom had

to exit quickly as water poured in. His spacesuit became

waterlogged, and there were a few tense moments before the

helicopter picked him up. His capsule, however, sank,

where it remained at the bottom of the sea until it was

found and retrieved in 1999. It has since been on a “tour”

of museums around the United States.

View of

earth taken by Astronaut John Glenn during his MA-6

spaceflight, February 20, 1962.

John Glenn, Jr. was the

first American to make an orbital flight, travelling three

times around the Earth in his Friendship 7, on February

20, 1962. He was the first American to see a sunrise and

sunset from space and the first photographer in orbit. The

only anxious moments of his flight came before and during

re-entry, when a signal received on the ground indicated

(erroneously, as it turned out) that the capsule's heat

shield had come loose. At one point, Glenn thought his

shield was burning up and breaking away. He ran out of

fuel trying to stop the capsule's bucking motion as it

descended through the atmosphere, but splashed down safely

40 miles (64 kilometres) short of his target. Glenn

returned to Earth a national hero, having achieved Project

Mercury's primary goal.

Astronaut John

Glenn is fitted for his space suit prior to lift-off.

Scott Carpenter's flight

on the Aurora 7 in May 1962 was much like Glenn's. He

splashed down 250 miles (400 kilometres) away from his

target, and it took about three hours for the rescue crew

to locate his capsule.

Walter “Wally” Schirra

became the first orbiting television star as he beamed a

telecast back to Earth from his Sigma 7 spacecraft that

October. He set a record: orbiting six times in a mission

that lasted nine hours and 13 minutes.

The final flight in the

series, in May 1963, lasted a record 34 hours/19 minutes,

and circled the Earth 22-1/2 times. The pilot, Gordon

Cooper in his Faith 7, released the first satellite from a

spacecraft-a six-inch (152-millimeter) sphere with a

beacon for testing the astronaut's ability to track

objects visually in space. His mission was so successful

that NASA decided to cancel the final scheduled flight.

Mercury program

astronaut group portrait. Front row, left to right, are

Walter M. Schirra, Jr., Donald K. Slayton, John H. Glenn,

Jr., and M. Scott Carpenter.

Back row, left to right, are Alan B. Shepard, Jr., Virgil

I. Grissom and L. Gordon Cooper

Taken together, the time

in space for the six piloted flights had totalled two days

and six hours. By the time of the last flight, in May

1963, the U.S. space program was looking ahead to its new

goal, announced by President John F. Kennedy only three

weeks after Shepard's suborbital flight, of reaching the

Moon, and by 1963, only 500 of the 2,500 people working at

NASA's Manned Spacecraft Centre in Houston were still

working on Mercury-the remainder was already busy on

Gemini and Apollo.

But Mercury had taken the

critical first step. It had demonstrated that humans could

survive in space, a spacecraft could be designed to launch

them into orbit, and that the crew could return safely to

Earth.