|

the

Sputnik triumph

and it so

annoyed the Americans!

Sputnik I.

Sir Isaac Newton, in his landmark

1687 scientific work Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica,

wrote,“If a leaden cannon ball is horizontally propelled by a powder

charge from a cannon positioned on a hilltop, it will follow a curving

flight path until it hits the ground … You can make it turn 10 degrees, 30

degrees and 90 degrees before it touches the ground. You can force it to

circle the Earth and even disappear into outer space, going away to

infinity.”

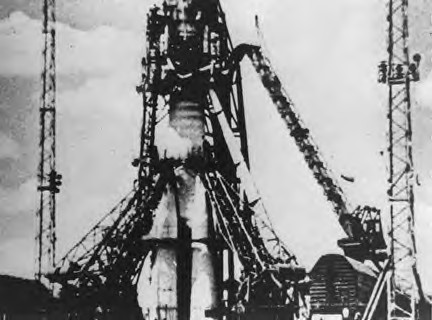

On the evening of October 4,

1957, Newton's hypothesis was proven correct. At 1912 Greenwich Mean Time,

an R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile lifted off from the Baikonur

Cosmodrome, on the steppes of Kazahkstan in the former Soviet Union,

carrying a 23-inch (58-centimeter) polished steel sphere called Sputnik.

About 100 minutes later, the 184-pound (93-kilogram) Sputnik (translated

as “satellite” or “traveling companion of the Earth”), trailing four metal

antennas, passed through the skies over the launch site confirming that a

human-made moon was now orbiting the Earth. The “Space Age” had begun.

Launch of Sputnik 1.

Baikonur, USSR.

Word of the successful launch was

relayed to Radio Moscow, and within minutes, terse bulletins flashed from

news agencies around the world announcing the historic event to an

unsuspecting and somewhat stunned populace. Shortwave radio operators soon

picked up a persistent “beep … beep … beep” signal broadcast from the

satellite as it passed silently overhead, travelling at 17,400 miles per

hour (28,003 kilometres per hour).

As news of the Soviet

accomplishment quickly spread by radio and television reports, untold

millions climbed onto rooftops, ventured into city parks, or ambled out to

dark backyards, all scanning the heavens for a brief glimpse of a rapidly

moving star. It was a communal experience that would later become known

simply as “Sputnik Night.”

In his best-selling book, Rocket

Boys, author (and retired NASA engineer) Homer H. Hickam, Jr. described

the night he first observed Sputnik as a 14-year-old. “I saw the bright

little ball, moving majestically across the narrow star field between the

ridgelines. I stared at it with no less rapt attention than if it had been

God Himself in a golden chariot riding overhead. It soared with what

seemed to me inexorable and dangerous purpose, as if there were no power

in the universe that could stop it. All my life, everything important that

had ever happened had always happened somewhere else. But Sputnik was

right there in front of my eyes in my backyard in Coalwood, McDowell

County, West Virginia, U.S.A. I couldn't believe it,” Hickam recollected.

The teenaged Hickam's feelings

were shared by one of the most powerful individuals in the U.S.

government, then-Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Baines Johnson. In his

memoir, The Vantage Point, Johnson recalled Sputnik Night with a sense of

unease and apprehension. “In the open West, you learn to live with the

sky. It is a part of your life. But now, somehow, in some new way, the sky

seemed almost alien,” wrote Johnson.

The world's shocked reaction to

the launch of Sputnik caught the Soviet government by surprise. The

October 5, 1957, issue of the official Communist party daily newspaper

Pravda barely acknowledged the event in a brief column halfway down the

front page. However, the Soviets were quick to capitalize on the enormity

of what The New York Times described in an editorial as “one of the

world's greatest propaganda-as well as scientific-achievements.” The

following day's issue of Pravda featured the banner headline “World's

First Artificial Satellite of Earth Created in Soviet Nation.”

Sputnik was launched as part of

the United Nations-sponsored International Geophysical Year (IGY), a

collaboration by 67 nations to explore the unknowns of the physical world

that actually 18 months, from July 1, 1957 to December 31, 1958. During

this period the United States had announced its intention to launch a

scientific satellite, Vanguard, possibly as early as November 1957. The

publicized target launch date for the American satellite was likely the

driving factor in the Soviet decision to launch Sputnik first in October.

The plans for a Sputnik, however,

had been widely reported in both Soviet and Western publications for

several years, and publicly acknowledged by the Soviets four months before

the actual launch. An official paper presented to IGY participants in June

1957, by the Soviet Academy of Sciences predicted that a satellite would

be launched within months and clearly outlined the satellite's approximate

launch site and anticipated speed.

The dog Laika was a

passenger on Sputnik 2.

On August 27, 1957, a Soviet

scientist, speaking at a conference in Colorado, indicated that his

Nation's satellites would pass over higher latitudes than their American

counterparts and broadcast on frequencies of approximately 20 and 40

megahertz. The clues were all in place, but were generally disregarded by

most in government and scientific circles because of what British

astronomer Sir Bernard Lovell called “American blind disbelief in the

powerful advance of Soviet science and technology.”

The American response to Sputnik

bordered almost on panic. The Chicago Daily News declared that if the

Soviets “could deliver a 184-pound ‘moon' into a predetermined pattern 560

miles out into space, the day is not far distant when they could deliver a

death-dealing warhead onto a predetermined target almost anywhere on the

earth's surface.” Newsweek magazine dolefully predicted that several dozen

Sputniks equipped with nuclear bombs could “spew their lethal fallout over

the U.S. and Europe.” Senator Lyndon Johnson envisioned a day when the

Soviets would be “dropping bombs on us from space like kids dropping rocks

onto cars from freeway overpasses,” while Senator Mike Mansfield ominously

announced, “What is at stake is nothing less than our survival.”

The one notable exception to the

immediate post-Sputnik hysteria was President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Although he had American nuclear-armed bombers remain constantly airborne

just four days before Sputnik's launch in response to Soviet development

of the intercontinental ballistic missile (which had been used to launch

Sputnik), Eisenhower did not even comment publicly on the launch until

October 9, when he issued a statement congratulating the Soviet

achievement.

Eisenhower's staid composure

concealed an ulterior motive. The president and the U.S. intelligence

community had been evaluating proposals for an orbiting reconnaissance

satellite, but had been grappling with the political ramifications of

Soviet reaction to over flights of its territory. The launch of Sputnik

effectively ended those concerns, allowing the United States to pursue a

policy of space as an “open platform,” establishing that national

boundaries did not extend into space. Donald Quarles, Eisenhower's

assistant Secretary of Defence, noted on October 7 that the Soviets “have,

in fact, done us a good turn, unintentionally, in establishing the concept

of freedom of international space,…” a principle which the Soviets could

not now refute since they had launched first.

The launch of Sputnik II on

November 3, 1957, ended any slim public perception of short-term American

parity in the emerging Space Race. As the United States was still

struggling to launch its IGY scientific satellite Vanguard, weighing all

of 3.25 pounds (1.5 kilograms), Sputnik II tipped the scales at 1,118

pounds (507 kilograms) and carried a living passenger, a mongrel dog named

Laika, along with sufficient life support supplies to keep the little dog

alive for 100 hours.

The United States' official

response to Sputnik was multi-pronged. School curriculum's with an emphasis

on science and mathematics were quickly established to prepare students

for the challenges ahead; the National Defence Education Act was enacted

to provide hundreds of millions of dollars in student loans, scholarships,

fellowships, and the purchase of scientific equipment for schools; support

was expanded for the National Science Foundation, and the Advanced

Research Projects Agency was created.

The shock of Sputnik was also

largely responsible for the establishment of the National Aeronautics and

Space Administration (NASA) in 1958 to conduct the United States' civilian

space efforts. Thus, the United States and the Soviet Union began a duel

for control of the heavens, the so-called Space Race” that consumed both

nations for the next 11 years, ending only when American astronauts first

set foot on the Moon on July 20, 1969.

|