|

the

Challenger Accident

Crewmembers of the STS 51-L

mission at pre-launch breakfast, January 28, 1986.

The

explosion that took the lives of the seven-member crew on board the Space

Shuttle Challenger on January 28, 1986, was one of those events that

prompt people to ask, “Where were you when…..?” Probably few peacetime

incidents have had as much impact, and few have received as much attention

from both the public as well as those involved with spaceflight, as this

tragedy has.

The

mission was planned much like many others, rather routine in fact, with

two payloads to launch and a number of experiments to be conducted on

board. Planned objectives were to launch a new communications

satellite-the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite-and flying of a module to

observe Halleys comet with two ultraviolet spectrometers and two cameras.

Other payloads were the Fluid Dynamics Experiment, the Comet Halley Active

Monitoring Program Phase Partitioning Experiment, and three Shuttle

Student Involvement Program experiments. A first-time activity was the

lesson-from-orbit that classroom teacher Christa McAuliffe planned to

teach. As well as McAuliffe, the other crew members were Francis R. Scobee,

commander; Michael J. Smith, pilot; mission specialists Judith A. Resnik,

Ellison Onizuka, and Ronald E. McNair; and non-NASA payload specialist

Gregory Jarvis, an employee of Hughes Aerospace.

The

launch, originally scheduled for January 22, had been postponed six times

because of bad weather and mechanical problems. When the decision was made

to launch, the air temperature was 36 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees

Celsius), cold for Florida, even in January.

Launch

finally took place at 11:38 a.m. Eastern Standard Time.

Main engine

exhaust, solid rocket booster plume and an expanding ball of

gas from the external tank is visible seconds after the

Space Shuttle Challenger accident on Jan. 28, 1986.

Photographic data later revealed that the first indication of a problem

occurred at 0.678 seconds into the flight, when a strong puff of grey

smoke spurted from the vicinity of the aft field joint on the right solid

rocket booster. The vaporized material streaming from the joint indicated

the absence of complete sealing action within the joint. Quickly,

observers saw eight distinctive puffs of increasingly blacker smoke. At

just under a minute into the flight, the first flickering flame would be

detected on image-enhanced film on the right solid rocket booster, and one

film frame later, the flame was visible without image enhancement. It

rapidly grew into a continuous, well-defined plume that was directed onto

the surface of the massive external tank, which held the fuel for the main

engines.

At 64

seconds came the first visual indication that the swirling flames from the

right solid rocket booster had breached the external tank. Within 45

milliseconds of the breach, a bright, sustained glow developed on the

black-tiled underside of the Challenger between it and the external tank.

Less than 10 seconds later, at an altitude of 46,000 feet (14,325

meters), the Challenger was totally engulfed in an explosive burn. At 73

seconds after lift-off, it exploded, claiming the crew and vehicle while

millions watched in horror on their televisions.

Moments

after the explosion, all mission data, flight records, and launch

facilities were impounded. Within an hour, NASA's associate administrator

for space flight, Jesse Moore, named an expert panel to investigate the

disaster.

On

February 3, President Ronald Reagan announced the formation of a

presidential commission to investigate the accident. The commission was

headed by former secretary of state and attorney general William P. Rogers

and consisted of persons not connected with the mission. The commission

immediately began a series of hearings that dealt with all areas of the

Space Shuttle program. In all, the commission interviewed more than 160

individuals and held more than 35 formal panel investigations, generating

almost 12,000 pages of transcript. Almost 6,300 documents, totalling more

than 122,000 pages and hundreds of photographs were examined and became

part of the commission's permanent database and archives.

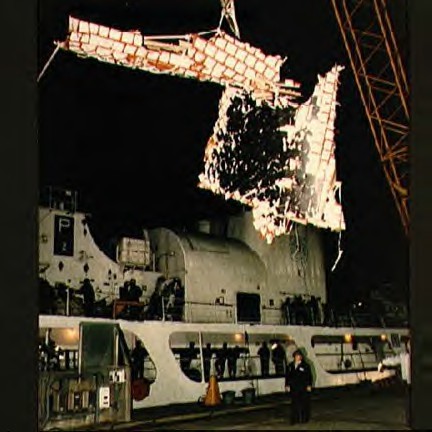

Wreckage from the Space Shuttle

mission 51-L mission retrieved from the Atlantic Ocean

by a flotilla of U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Navy vessels was returned to

the Trident Basin

at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station aboard the U.S. Coast Guard cutter

Dallas

Early in

its investigations, the commission began to learn of the troubled history

of the solid rocket motor joint and seals. Commission members discovered

the first indication that the manufacturer of the solid rocket booster,

Morton Thiokol, had initially recommended against launch the night before

because of concerns regarding the effects of the low temperature on the

joint and seal. Following further testimony, Chairman Rogers issued a

station noting that “the process [leading to the launch of Challenger] may

have been flawed.”

The

commission released its report and findings on the cause of the accident

on June 9, 1986. The consensus of the commission and participating

investigative agencies was that the loss of Challenger was caused by a

failure in the joint between the two lower segments of the right solid

rocket motor. The specific failure was the destruction of the O-ring seals

that were intended to prevent hot gases from leaking through the joint

during the propellant burn of the rocket motor. The evidence assembled by

the commission indicated that no other element of the Space Shuttle system

contributed to this failure.

In

addition to this primary cause, the commission identified a contributing

cause of the accident relating to the decision to launch. The commission

concluded that failures in communication resulted in launch decision based

on incomplete and sometimes misleading information. Further, engineering

data and management judgments conflicted and NASA's management structure

permitted internal flight safety problems to bypass key Shuttle managers.

Neither concerns regarding the low temperature and its effect on the

O-ring nor the ice that formed on the launch pad had been communicated

adequately to senior management or been given sufficient weight by those

who made the decision to launch. In addition, the heavy emphasis on

maintaining the schedule of Shuttle launches and an ambitious flight rate

diluted the resources available for a single mission and very likely

compromised quality.

The

problem with the Space Shuttle's Solid Rocket Booster joint began with its

faulty design and increased as both NASA and Thiokol management first

failed to recognize the problem, then failed to fix it, and finally

treated it as an acceptable flight risk. NASA minimized the growing

problem in its management briefings and reports, and Thiokol's stated

position was that "the condition is not desirable but is acceptable." At

no time did management either recommend a redesign of the joint or call

for the Shuttle's grounding until the problem was solved.

The

findings of the commission determined that the genesis of the Challenger

accident-the failure of the joint of the right solid rocket motor-began

with decisions made in the design of the joint and in the failure by both

Thiokol and NASA to understand and respond to facts obtained during

testing.

In its

report to the President, the commission unanimously adopted nine

recommendations. These ranged from the obvious redesign of the solid

rocket booster joints to recommendations relating to management,

communications, and safety. The commission also recommended that NASA slow

the pace of its launches. Although critical of the agency, the commission

also urged that the country continue to support NASA as a “national

resource” and applauded the agency's achievements.

At the

same time that the commission was meeting, NASA was working on defining

and implementing the actions it would take that would allow resumption of

Shuttle flights. This included redesign of the solid rocket motor that

eliminated the weakness that had led to the accident. The agency also

reviewed every element of the Shuttle system and added features to improve

safety including a drag-chute system and upgrades of the orbiters' tyres,

brakes, and nose-wheel steering mechanism. A crew escape system that would

allow astronauts to parachute from the orbiter under certain conditions

was also added. Finally, a new, streamlined management team was also put

in place that included experienced astronauts.

NASA

selected the orbiter Discovery for the “return to space” mission,

designated STS-26. On September 29, 1988, it blasted off from Kennedy

Space Centre, carrying a new Tracking and Data Relay Satellite identical

to the one that had been destroyed two and a half years before. The

Shuttle had returned to the skies, a much safer program. And never again

would any Shuttle launch be considered “routine.”

|