The U.S.

Air Force started its first military space program in 1956. Known as

Weapons System 117L (or more simply, WS-117L), it was an effort to develop

a television-based reconnaissance satellite for spying on the Soviet

Union. The program limped along under funded until after the Soviet launch

of Sputnik, in October 1957, when it shifted into high gear. At this

point, the U.S. Air Force began developing two types of satellites. One

was a system, soon named Samos, that would take a picture on film and

develop it in orbit, scanning it like a computer scanner and relaying the

data to the ground over a radio link. This system was slow, and the

satellites could transmit only a few dozen images a day, which was too

little to have any value. The Samos readout system was cancelled in the

early 1960s.

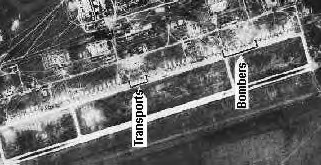

First imagery taken by CORONA -

Mys Shmidta Air Field, USSR 18 Aug 1960.

The

other system, which was led by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with

substantial Air Force participation, was named CORONA in February 1958

(the names of U.S. intelligence satellites are always written in all

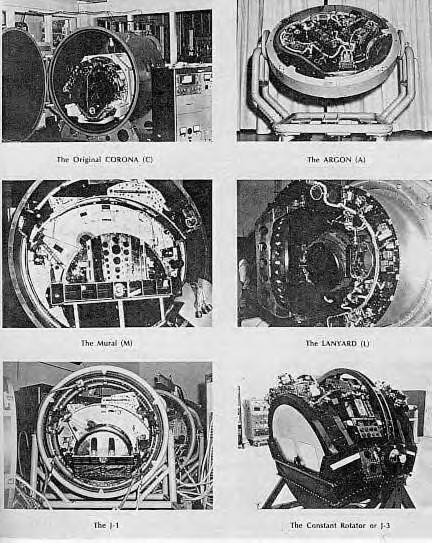

upper-case letters). This system used a panoramic camera on a stabilized

satellite to take a long, thin image on a 70-millimeter strip of film.

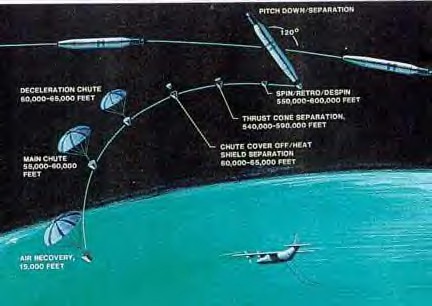

CORONA recovery sequence.

The

film wound on a reel inside a small bucket-shaped re-entry vehicle and

re-entered the atmosphere, where it was snatched out of the air by a

passing airplane while hanging from its parachute. CORONA could see

objects as small as six to nine feet (two to three meters) on a side. Only

the film was saved; each satellite was used for only a single mission. The

first successful mission was in August 1960 and more than 120 satellites

were launched until the early 1970s, when the system was replaced by a

much more massive satellite commonly referred to as the “Big Bird,” but

actually named the KH-9 HEXAGON.

CORONA image showing transport

vehicles and bombers.

Beginning in 1960, the Air Force began developing a new, high-resolution

satellite system called the KH-7 GAMBIT. This satellite could take very

powerful images of a small area on the ground, allowing an intelligence

analyst to look at targets as small as 1.5 feet (0.5 meters) across. By

1967, an even more powerful version entered service, allowing experts to

see objects as small as about three inches. This was the most powerful

satellite ever operated by any nation, but it did not allow operators to

read license plates, like Hollywood satellites could.

The CORONA cameras.

The

Soviet Union also started its own reconnaissance satellite program in the

late 1950s. This effort, known as Zenit, used a modified version of the

Vostok piloted spacecraft, equipped with several cameras that took still

images. The entire large re-entry vehicle would return to Earth with both

film and cameras, allowing the cameras to be reused. The Soviets also

developed a higher-resolution system called Yantar, versions of which are

still in use today.

After

Sputnik, the U.S. Navy began developing a small satellite for intercepting

Soviet radar transmissions. Several of these satellites, named GRAB, and

later DYNO, were launched starting in 1960 and followed by a better series

of satellites named POPPY. They intercepted the electronic signals emitted

by ground-based aircraft search radars, allowing the Navy and the Air

Force Strategic Air Command to locate the radar positions and develop ways

of avoiding or jamming them. A more capable system, called PARCAE, used

groups of small satellites. It could locate ships at sea based upon their

radar and radio transmissions by triangulating their position.

Starting

in 1961, all of these intelligence collection satellites were operated by

a highly secret agency within the Department of Defence called the

National Reconnaissance Office, or NRO. The NRO was not even publicly

acknowledged until 1992.

Throughout the 1960s, the United States and the Soviet Union operated much

bigger and better versions of their film-return satellites and signals

intelligence satellites. In the late 1960s the U.S. Air Force began

operating a communications intelligence satellite named CANYON that

intercepted Soviet telephone transmissions. Follow-on versions of this

satellite, named VORTEX and MERCURY, continued to operate into the 21st

century. In the early 1970s, the CIA deployed a satellite named AQUACADE

for intercepting the faint radio signals from Soviet missile tests, using

a giant mesh dish for detecting the electronic whispers. Modern versions

named MERCURY and ORION were launched in the 1980s, and even more upgraded

versions were launched in the 1990s. These satellites are believed to have

truly massive antennas that unfurl in geosynchronous orbit.

The one

major limitation of the film-return satellites like CORONA, HEXAGON,

GAMBIT and Zenit and Yantar is that it could take days for their images to

reach the eyes of an intelligence expert. Both countries investigated

whether piloted reconnaissance satellites could partly fulfil this role.

The U.S. Air Force's Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) was designed to

assess the capabilities and potential of military operations in space but

was abandoned in 1969, before it ever flew. The Soviet Union launched

several Almaz military space stations during the 1970s before abandoning

its effort. Both countries realized that humans and sensitive optics were

a bad combination.

Throughout the 1960s both the U.S. Air Force and the CIA sought to develop

a “real-time” imaging satellite system that could transmit its images to

the ground as fast as it took them. The CIA sponsored the development of

what became the Charge Coupled Device, or CCD, like that used in modern

digital cameras. In December 1976, the NRO launched the first satellite

using this new technology, called the KH-11 KENNAN. The KH-11 allowed

images to reach an intelligence expert, or the desk of the President of

the United States, within minutes. It too revolutionized intelligence

collection and by the 1980s the United States no longer launched

film-return satellites. These satellites look much like NASA's Hubble

Space Telescope, with a large mirror inside a long tube, except they point

at the Earth rather than the stars. They can probably see objects about

the size of a softball. Versions of the KH-11 equipped with some infrared

capability (later called CRYSTAL and now called by some highly-secret code

name) continue to operate today and their images are vital to U.S.

military operations.

KH-11 photo of the Shifa

Pharmaceutical Plant, Sudan.

The

Soviet Union continued to lag behind the United States and did not orbit

its own real-time reconnaissance satellite until the 1980s. After the Cold

War ended, Russian military space launches diminished to a trickle and

they launched fewer reconnaissance satellites. Surprisingly, the Russians

still launch the occasional film-return satellite, possibly because their

real-time satellite, although fast, cannot take high-quality photos.

The

final major limitation to imaging satellites was clouds. In the 1960s, the

U.S. Air Force launched a radar satellite named QUILL, capable of peering

through clouds, but it could not see much detail. In the late 1980s, the

NRO launched the first of a new class of large imaging satellites, named

LACROSSE (and later ONYX). These satellites probably see images on the

ground about three feet (one meter) across.

China

also developed film-return satellites starting in the 1980s, and may have

a real-time reconnaissance satellite today. France led a consortium of

European countries during the 1990s and orbited its Helios reconnaissance

satellite. France has also sought to develop small signals intelligence

satellites as well. In the late 1980s, Israel launched its first imaging

satellite, called Ofeq, and has since followed with others. Other

countries, such as India, have also sought to develop a satellite

reconnaissance capability. But the emergence of commercial imaging

satellites in the late 1990s, capable of taking images of objects as small

as two feet (0.61 meter) across, means that a capability once available

only to the superpowers is now available to any country—or person—with a

credit card.