Artistďs conception of

Pioneer Venus spacecraft.

Since

the beginning of the space age in 1957, the United States and the Soviet

Union have sent dozens of probes to explore Mercury, Venus, and Mars, the

three inner planets. While many of these spacecraft failed to reach their

targets, many others have sent back valuable information.

For

decades, scientists and lay people have speculated on the possibility of

life on Mars. Therefore, it is not surprising that the so-called “Red

Planet” has been the object of most of our attention. Since 1960, humans

have tried to send probes to Mars 33 times. Of these, only ten have fully

succeeded in their objectives. Nine of these attempts have been American.

The

Soviet Union first launched two Mars probes in 1960, both of which failed

due to defective launch vehicles. Three modified probes, one of which was

actually intended to land on Mars, were dispatched in 1962. The first,

known officially as Mars 1, launched on November 1, 1962, became

the first spacecraft sent by any nation to fly past Mars. Ground

controllers eventually lost contact three months before the probe silently

flew by Mars in June 1963 at a distance of 197,000 kilometres (122,410

miles).

The

first true successes came when the National Aeronautics and Space

Administration (NASA) launched Mariner 3 and Mariner 4 to

fly past Mars in November 1964. While Mariner 3 failed, Mariner

4 was a spectacular success, the first great achievement of deep space

exploration. The spacecraft flew by Mars in July 1965 and sent back 22

photographs of the surface of Mars, showing the planet to be an ancient

moon-like body with an abundance of craters. NASA followed this success

with Mariner 6 and Mariner 7, both of which flew by Mars in

July and August 1969, returning more information about its surface.

Following these flyby missions, NASA's Mariner 9 became the first

spacecraft to go into

orbit around Mars in November 1971. During its yearlong mission,

Mariner 9 mapped 85 percent of the planet's surface in unprecedented

detail. It identified 20 volcanoes including Olympus Mons, a giant feature

that dwarfed anything similar on Earth.

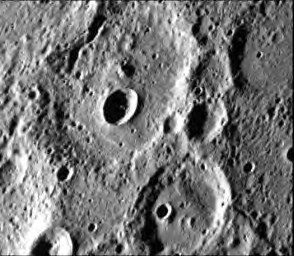

Fresh crater in centre of older

crater basin on Mercury, taken by Mariner 10.

Mariner 9's success set the stage for perhaps the most ambitious

missions ever launched to Mars -the Viking 1 and 2 missions.

These two spacecraft, each comprising a lander and an orbiter, were

designed to spend months studying the surface of Mars from orbit and down

on the ground. The two landers successfully set down on Mars in July and

September 1976, respectively. Their first clear photographs of the Martian

surface showed a cratered terrain resembling that of the Moon. Both

landers also conducted experiments to detect signs of life, but the

results were inconclusive. The two orbiters returned more than 50,000

photographs of the surface over the course of several years, mapping 97

percent of the surface.

The

Soviets were much less fortunate in their Mars missions. Between 1969 and

1973, the Soviets tried nine times to send spacecraft to Mars. Although

several of them reached the planet, only Mars 5 in 1973-74,

successfully succeeded in orbiting and photographing the planet. More than

a decade later, in 1988-89, the Soviets fared no better when they launched

the Fobos twin probes to survey both Mars and its oddly shaped moon

Phobos. Both spacecraft failed to achieve their primary goals. A final

mission in 1996, the ambitious Mars 8 project, comprising an

orbiter, two surface penetrators, and two independent stations, also

failed.

NASA,

meanwhile has had an uneven success rate in more recent years. Mars

Observer, a 2.5-ton spacecraft designed to map the surface of Mars,

failed in 1992 to enter orbit around Mars. Mars Global Surveyor,

launched in 1996, succeeded in entering orbit around Mars in September

1997. It has continued to return high-quality data and photographs of the

red planet. The spacecraft has tracked the evolution of dust storms and

most important, found convincing evidence for the presence of liquid water

on or near the surface. Mars Pathfinder, also launched in 1996, was

another stunning success. The spacecraft successfully landed on Mars on

July 4, 1997, and released a 10.5-kilogram (23-pound) rover named

Sojourner that trekked around the landing area collecting information and

taking spectacular photographs.

Volcanoes Ceraunius Tholus and

Uranius Tholus, taken by Mars Global Surveyor Mars orbiter camera, April

18, 2002.

Two of

NASA's more recent missions, Mars Climate Orbiter (launched in

1998) and the Mars Polar Lander (launched in 1999), failed to

achieve either of their objectives. Fortunately, a third spacecraft, the

2001 Mars Odyssey probe, successfully entered orbit around Mars in

October 2001 to begin three years of mineralogical analysis from orbit.

A

Japanese spacecraft, Nozomi, is also on its way to Mars, and is

expected arrive in December 2003.

The

Soviets have fared much better in their missions to Venus. Of the 35

probes launched, 22 have succeeded in their objectives. Of these, 17 have

been Soviet. They were the first to attempt to send probes to Venus when

they launched two spacecraft to Venus in 1961, one of which actually flew

past the mysterious planet, although by then its radio system had failed.

The

first successful mission to Venus-in fact, the first successful planetary

mission-was Mariner 2. The American spacecraft flew past Venus in

December 1962 at a distance of 21,600 miles (34,762 kilometres) and

returned data about its atmosphere.

The

Soviets scored a big success when in March 1966, when Venera 3

reached the surface of Venus, becoming the first space probe to ever

impact another planetary body. Through the late 1960s, the Soviets

continued to send probes to Venus to obtain data from the inhospitable

surface, but none succeeded until Venera 7 returned the first

information from the surface in December 1970. For 23 minutes, the lander

returned data about conditions on the ground before succumbing to the

extreme heat and pressure. It was the first time that any probe had

returned information from the surface of another planet.

Two

Soviet probes launched in 1975, Venera 9 and Venera 10,

returned the first photographs from the surface of Venus. These images

showed flat rocks spread around the landing area. Two new probes,

Venera 11 and Venera 12, landed on the planet in 1978 (although

they were unable to return photographs). In 1982, another pair, Venera

13 and Venera 14, returned the first color photographs of the

surface. Probes such as Venera 15 and Venera 16 also mapped

the Venusian surface from orbit using high-powered radars. Perhaps the

most ambitious Soviet mission to Venus was the successful Vega 1

and Vega 2, launched in 1984. The two spaceships were each made up

of landers, atmospheric balloons, and flyby probes for encounters with

Halley's

comet. The French-made balloons, each weighing about 46 pounds (21

kilograms), transmitted important data about the atmosphere as they

drifted slowly through the Venusian skies.

NASA has

also mounted several ambitious missions to Venus. These have included the

Pioneer Venus missions, comprising an orbiter with a powerful radar, and a

spacecraft with three small atmospheric entry probes. The two spacecraft

were launched in 1978. The smaller probes scattered through the atmosphere

and collected data as they flew down to the surface. Data indicated that

the Venusian atmosphere is relatively clear below about 19 miles (30

kilometres).

Magellan combined radar and

altimetry image of three volcanoes.

Since

then, NASA has conducted only one mission to Venus, the Magellan

orbiter flight. Launched in 1989, Magellan successfully entered

orbit around Venus in August 1990. By the time its mission ended in 1994,

Magellan had successfully mapped 98 percent of the surface of the

planet using sophisticated radars that could peer through the thick

atmosphere. The spacecraft discovered that at least 85 percent of the

surface of the planet is covered with volcanic flows.

Only one

spacecraft has been sent to the small planet closest to the Sun, Mercury.

In late 1973, NASA launched Mariner 10, which on its way to

Mercury, passed by Venus and used that planet as a “gravity assist” to

send it toward Mercury. Through 1974, Mariner 10 flew by Mercury

three times, the closest at a range of only 203 miles (327 kilometres).

Each time, the spacecraft returned the first photographs of the surface of

the planet. The photos showed a terrain similar to the Moon. Maximum

daytime temperatures were on the order of 369° F (187° C) although

temperatures in the shade went as low as -297° F (–183° C). Contact with

Mariner 10 was lost in March 1975.