|

ballistic missiles

The first Thor

intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM)

launch from Vandenberg AFB, December 16, 1958

The

United States and Soviet Union first started developing intercontinental

ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in the 1950s, because there was no way for a

target to defend against them. Missile warheads are so small and travel so

fast that it is virtually impossible for a defensive weapon to hit them-a

fact that remains almost as true today as it was during the 1950s. But for

decades, the United States and Russia have spent tremendous amounts of

money trying to develop a defence against ballistic missiles.

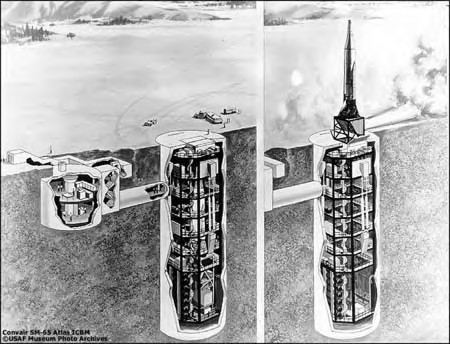

The Strategic Air Command's first

intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) was the Convair B-65 Atlas

(later redesignated SM-65). The Atlas became operational in 1959. Because

of the vulnerability

of the Atlas while above ground, an underground silo was developed.

An elevator raised it to ground level for launching. While on alert duty,

the Atlas missile

was maintained in the fully raised (above ground) position since it could

not be launched from its underground silo.

The

first serious study of what was called an “anti-missile missile” dates to

as early as 1956, when a U.S. scientific group evaluated the challenges of

shooting down ballistic missile warheads. They realized that warheads were

small and might not show up on radar, and responding to an attack in time

would be difficult. But the biggest problem was getting a missile into the

vicinity of the attacking warhead and destroying it. Because they could

not get close to their targets, early anti-missile proposals all relied on

nuclear warheads, which had a wide enough explosive radius that they could

compensate for the inaccuracy of the missile. In the mid-1950s, the U.S.

Army built an “anti-ballistic missile” (ABM) known as the Nike-Zeus with

some anti-missile capabilities, but by 1959, President Dwight D.

Eisenhower's Presidential Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) ruled that

Nike-Zeus was too slow, too vulnerable to attack, and could not

differentiate between real warheads and decoys.

By the

early 1960s, U.S. Air Force scientists had evaluated the possibility of

using lasers to burn missile warheads in flight but determined that the

lasers could not produce enough energy to damage a warhead, which was

small and fast and already designed to withstand tremendous heat during

re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. The U.S. Army began developing new

radars encased in hardened structures and a faster missile named the

Sprint; the new radars and missile were combined into a system named

Nike-X. In 1966, the highest level military leaders recommended that this

system be deployed to defend the entire United States against Soviet ICBM

attack, a so-called “area defence.” But Secretary of Defence Robert

McNamara resisted. Instead, McNamara pushed the development of

independently targetable re-entry vehicles, or MIRVs, which allowed a

single ICBM to attack multiple targets. This assured that no attack on the

United States could destroy a large enough number of American ICBMs so as

to prevent it from staging a devastating counterattack, and supposedly

made a Soviet ICBM attack unthinkable by the Soviet military.

Titan I ICBM launch at Vandenberg

Air Force Base, December, 1960

In late

1967, McNamara agreed to start work on a modified, scaled back version of

the Nike-X system dubbed Sentinel. McNamara argued that this reduced

system would focus on the Chinese missile threat rather than the Soviet

threat and as such, would be less provocative. Sentinel would have

resulted in basing large numbers of powerful nuclear warheads atop Spartan

missiles around major American cities.

In early

1969, the new administration under President Richard Nixon re-evaluated the

Sentinel system and scaled it back dramatically, renaming it Safeguard.

Instead of an area defense system, Safeguard would be a “point defence”

system intended to protect ICBM sites. By 1970, both the United States and

Soviet Union had approximately the same number of ICBMs, and the two

countries started discussing arms control, signing the Strategic Arms

Limitation Treaty (SALT) in 1971. In May 1972, they both signed the

Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. This treaty limited both countries to

two ABM sites each, one to protect the Nation's capital and the other to

protect an ICBM site. It also restricted testing of systems capable of

shooting down ICBMs as well as deployment of new ABM radars deep inside a

Nation's territory.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, while the United States was developing its

ABM systems, the Soviet Union was also conducting a massive ABM

development program. The Soviet military tested huge radars and powerful

missile interceptors at a big facility known as Sary Shagan. But despite

all of their efforts, the Soviets were unable to develop an effective

missile defence system. They started a system for defending Moscow in the

1960s and eventually completed it after a number of setbacks.

Boeing LGM-30A Minuteman I. The

Minuteman I, formally known as the SM-80,

was a second generation intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) using

solid propellants rather than liquid fuels.

In early

1975, the United States deployed its ABM system at Grand Forks, North

Dakota, to defend ICBM silos. But Congress closed the facility within a

year because there was no way that its 100 missile interceptors could

defend against thousands of incoming Soviet warheads. The Soviet Union

maintained its limited ABM system around Moscow and updated it starting in

the 1980s. But the system never worked properly. Critics within the Soviet

military noted that the defensive system itself would detonate dozens of

nuclear weapons directly over the city. Proponents of the system

rationalized that the system was intended to defend against a much more

limited missile attack from China, but outdated technology made even this

reduced task seem nearly impossible.

On March

23, 1983, President Ronald Reagan gave a speech announcing a major shift

in American defence policy. Reagan declared that the United States would

seek to develop a missile shield to defend the entire country against

Soviet ICBM attack. This shield would rely upon many highly advanced and

unproven technologies, such as lasers and particle beams, and much of it

would presumably be deployed in space. The lasers would attack Soviet

ICBMs while they were still relatively slow and lifting off the ground,

when they were most vulnerable (a period known as the “boost phase”). The

Soviets had also started developing a large radar deep inside their

territory near Krasnoyarsk that directly violated the ABM Treaty. When the

Americans discovered this in July 1983, relations deteriorated.

Critics

immediately labelled Reagan's defence plan “Star Wars” and ridiculed it for

being totally unrealistic. Reagan soon established the Strategic Defence

Initiative, or SDI, to develop the advanced technologies necessary for

effective missile defence. The SDI budget grew to nearly three billion

dollars a year, but even so, many of its most advanced technologies proved

beyond reach. In the late 1980s, SDI plans were scaled back. Instead of

lasers, one proposed solution was to use thousands of small orbiting

interceptors nicknamed “Brilliant Pebbles.” These would be combined with

many small orbiting sensors nicknamed “Brilliant Eyes.” Both proposals

ultimately led to a new approach to spacecraft design: an effort to

develop smaller, cheaper spacecraft. Despite the expenditure, SDI did not

make the kind of progress necessary to achieve Reagan's grand vision, but

it did greatly concern Soviet military and government leaders, who often

had more faith in American technology than the Americans did themselves.

President George H.W. Bush scaled back the SDI program after the end of

the Cold War but still sought to develop some form of missile defence. The

Iraqi use of Scud missiles during the 1991 Persian Gulf War demonstrated

that American troops abroad were also at risk from missile attack. This

threat prompted greater focus on so-called “theater” ballistic missile

defences to shoot down shorter-range missiles like the Scud, which are

slower and easier to hit than ICBMs.

After

Bill Clinton defeated Bush in the 1992 presidential election, he scaled

back the effort even further and focused it on developing several ground

and sea-based interceptors for defending against a small attack from

nations such as North Korea, Iraq, and Iran. These interceptors would

directly hit their targets at high speed and did not need a warhead. The

U.S. Air Force also began work on an Airborne Laser (ABL) that would be

mounted on a converted Boeing 747 airplane and used to shoot down missiles

like the Scud. The Strategic Defence Initiative Organization was renamed

the Ballistic Missile Defence Organization (BMDO).

For the

next eight years, Clinton continued missile defence research at a slower

pace. But in 1998, North Korea surprised the world by launching a

three-stage ballistic missile over Japan. This prompted renewed debate

within the United States about the threat from ballistic missiles, and

presidential candidate George W. Bush made missile defence a key part of

his campaign. When Bush was sworn in as president in January 2001, he

quickly moved to increase missile defence development, pushing deployment

of a small system based in Alaska that could intercept a small number of

ICBMs launched at the continental United States. In December 2001, Bush

announced his intention to withdraw the United States from the ABM Treaty.

Such a move was necessary if the United States was going to test more

advanced systems that would otherwise violate the treaty.

|