|

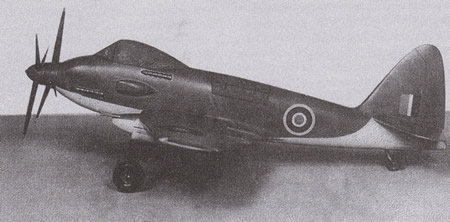

Fairey Firefly

A Fairey Firefly F.Mk I of 1772nd Squadron Royal Navy - H.M.S.

Indefatigable 1944

Before World War 11 Fairey designed a light bomber, P.4/34, from which

evolved the Fulmar naval two-seat fighter to Specification 0.8/38. A

total of 600 of these slender carrier-based aircraft served during the

war with various equipment and roles. The Firefly followed the same

formula, but was much more powerful and useful. Designed to N.5/40 - a

merger of N.8139 and N.9139 - it was a clean stressed-skin machine with

folding elliptical wings housing the four cannon and with the trailing

edge provided with patented Youngman flaps for use at low speeds and in

cruise. Unlike the installation on the Barracuda, these flaps could be

recessed into the wing.

The

pilot sat over the leading edge, with the observer behind the wing. The

main wartime version was the Mk 1, widely used from the end of 1 943 in

all theatres. Fairey and General Aircraft built 429 F.1s, 376 FR.Is

with ASH radar and then 37 NF.2 night fighters. There followed the more

powerful Mk Ill, from which derived the redesigned FR.4 with two-stage

Griffon and wing-root radiators. There were 160 of these, 40 going to

the Netherlands and the rest serving in Korea, with the 352 Mk 5s with

folding wings. There were FR, NF and AS (anti-submarine) Mk 5s. and

they were followed by the 1 33 specialised AS.6 versions with all role

equipment tailored to anti-submarine operations. The 1 51 AS.7s rounded

off production, this being a redesigned three-seater, with new tail and

wings and distinctive beard radiator. More than 400 Fireflies were

rebuilt in the 1950s as two-cockpit T.1 s or armed T.2s, or as various

remotely piloted drone versions (U.8, U.9, U.10). Some were converted

as target tugs and for other civil duties.

Variants

Designed to Admiralty Specification N.5140, calling for a two-seat

reconnaissance fighter, the Fairey Firefly represented a considerable

advance over the company's earlier Fulmar. A cantilever low-wing

monoplane of all-metal construction, it had a conventional tail unit,

retractable tailwheel landing gear and accommodation for the pilot and

navigator/radio-operator in separate enclosed cockpits. Power was

provided by a 1,730 hp (1290 kW) Rolls-Royce Griffon IIB engine, but

later production Firefly F.Mk 1 aircraft had the 1,990 hp (1484-kW)

Griffon XII. The first of four development aircraft was flown on 22

December 1941, and the first production Firefly F.Mk 1 aircraft were

delivered in March 1943. A total of 459 of this version was built, 327

by Fairey and 132 by General Aircraft under sub-contract. The addition

of ASH radar beneath the engine identified the Firefly FR.Mk 1, of

which 236 were built, and a number of Firefly F.Mk Is modified to

Firefly FR.MK 1 standard had the designation Firefly F.Mk IA. A Firefly

NF.Mk 11 night-fighter version was developed, but when it was realised

that its AI Mk 10 radar could be pod mounted beneath the engine, as

with the ASH radar of the Firefly FR.MK 1, the planned 328 aircraft

programme was cancelled. Instead, 140 Firefly FR.MK Is were modified on

the production line to Firefly NF.Mk 1 configuration, the 37 Firefly

NF.Mk IIs that had been built being converted back to Mk 1 standard.

Post-war Mk 1 conversions included the unarmed dual-control Firefly

T.Mk 1 pilot trainer, the cannon armed Firefly T.Mk 2 operational

trainer, and the Firefly T.Mk 3 used for training in ASW operations. A

few were also converted as Firefly TT.Mk 1 target tugs.

Only a prototype of the Firefly F.Mk Ill with Griffon 61 engine was

built, development being concentrated instead on the Firefly F.Mk IV.

This had a 2,250 hp (1678 kW) Griffon 74 engine and new outer wing

nacelles that could both carry fuel, or an ASH scanner (port) and fuel

(starboard). About 160 were built, and the first Firefly FR.Mk 4

delivered in July 1946; some were converted later to Firefly TT.Mk 4

standard. The Firefly Mk 5 and Firefly Mk 6 were similar externally to

the Mk 4, the first aircraft of each variant flying in December 1947

and March 1949 respectively. Some 352 Mk 5s were built in versions

designated Firefly FR.Mk 5, Firefly NF.Mk 5 and Firefly AS.Mk 5, the

last with American sonobuoys and equipment that distinguished it from

the British-equipped Firefly AS.Mk 6 of which 133 were built. A few

Firefly T.Mk 5 trainers, and Firefly TT.Mk 5 and Firefly TT.Mk 6 target

tugs were converted in Australia from Firefly AS.Mk 5s.

The

first production Griffon 59-powered Firefly AS.Mk 7 was flown in

October 1951, this reintroducing the beard radiator that had caused

problems with the sole Mk Ill. Intended as an ASW aircraft

accommodating two radar operators, few Fireflys AS.Mk 7s were built as

such, the majority being completed as Firefly T.Mk 7 ASW trainers

within a Mk 7 production of 151. Later conversions to pilotless target

aircraft were carried out by Fairey, these including 34 Firefly U.Mk 8

aircraft converted from Firefly T. Mk 7s, and 40 similar Firefly U.Mk 9

conversions from Mk 4 and Mk 5 aircraft. They were used for missile

development, and by the Royal Navy as targets for its Firestreak-armed

fighters and Seaslug-carrying ships.

Fireflies entered service first with No. 1770 Squadron at Yeovilton,

Somerset, on 1 October 1943. Later embarked on HMS Indefatigable, they

were active in operations against the German battleship Tirpitz in

Norway during July 1944. They also saw action against Japanese oil

refineries in Sumatra, in attacks on the Carolines and against shipping

and ground targets in the Japanese home islands. In 1950, after war

broke out in Korea, Firefly Mk 5s were operated from Australian and

British light fleet carriers, and in 1954 the type was in action in the

ground-attack role in Malaya. Just over two years later the Firefly was

retired after 13 years of valuable service.

Specifications (Fairey Firefly AS.Mk 5)

Type: Two Seat Naval Reconnaissance Fighter / Anti Submarine Strike

Aircraft

Design: Fairey Aviation Design Team

Manufacturer: The Fairey Aviation Company

Powerplant: (AS.Mk 5) One 2,250 hp (1678 kW) Rolls-Royce Griffon 74

12-cylinder Vee piston engine. (Mk I up to No 470) One 1,730 hp (1290

kW) Rolls-Royce Griffon IIB 12-cylinder Vee liquid-cooled; (from No

471) 1,990 hp (1485 kW) Griffon XII. (Mks 4-7) One 2,250 hp (1678 kW)

Griffon 74 12-cylinder Vee piston engine.

Performance: (AS.Mk 5) Maximum speed 386 mph (618 km/h) at 14,000

ft (4265 m); cruising speed 220 mph (354 km/h); service ceiling 28,000

ft (8534 m). (Mk I) Maximum speed 316 mph (509km/h); initial climb rate

1,700 ft (518m) per minute; service ceiling 28,000 ft (8534 m). (Mk 4)

Maximum speed 386 mph (618 km/h); initial climb rate 2,050 ft (625 m)

per minute; service ceiling 31,000 ft (9450 m).

Range: (AS.Mk 5) 1300 miles (2092 km) on internal fuel. (Mk I) 580

miles (933 km) on internal fuel. (Mk 4) 760 miles (1223 km) on internal

fuel.

Weight: (AS.Mk 5) Empty 9,674 lbs (4388 kg) with a maximum take-off

weight of 16,096 lbs (7301 kg). (Mk I) Empty 9,750 lbs (4422 kg) with a

maximum take-off weight of 14,020 lbs (6359 kg). (Mk 7) Empty 11,016

lbs (4997 kg) with a maximum take-off weight of 13,970 lbs (6337 kg).

Dimensions: (Mk 4 - 6) Span 41 ft 2 in (12.55 m); length 37 ft 11

in (8.51 m); height 14 ft 4 in (4.37 m); wing area 330.0 sq ft (30.66

sq m). (Mk I - III) Span 44 ft 6 in (13.55m); length 37 ft 7 in (11.4

m); height 13 ft 7 in (4.15 m).

Armament: (Mk I) Four fixed 20 mm Hispano cannon in wings and

underwing racks for up to two 1,000 lbs (454 kg) of bombs or sixteen 60

lbs (27 kg) rocket projectiles. (Mk 4 and 5) usually similar to 1 in

most sub-types. (Mk 6) no guns, but underwing load increased to 3,000

lbs (1362 kg) and varied. (Mk 7) no guns, but underwing load remained

at 3,000 lbs (1362 kg) and equipment changed.

Variants: Firefly F.Mk 1, Firefly FR.Mk 1, Firefly F.Mk IA, Firefly

NF.Mk 11, Firefly NF.Mk I, Firefly T.Mk 1, Firefly T.Mk 2, Firefly T.Mk

3, Firefly F.Mk III, Firefly F.Mk IV, Firefly FR.Mk 4, Firefly TT.Mk 4,

Firefly Mk 5, Firefly Mk 6, Firefly FR.Mk 5, Firefly NF.Mk 5, Firefly

AS.Mk 5, Firefly AS.Mk 6, Firefly TT.Mk 5, Firefly TT.Mk 6, Firefly,

AS.Mk 7, Firefly T.Mk 7 ASW, Firefly U.Mk 8, Firefly U.Mk 9.

Avionics: AI Mk X radar, ASH Scanner, sonobuoys.

History: First flight 22 December 1941; first production F.1 26

August 1942; production FR.4. 25 May 1945; final delivery of new

aircraft May 1955.

Operators: United Kingdom (RN), Canada (RCN), Australia.

Number Built: ~1533

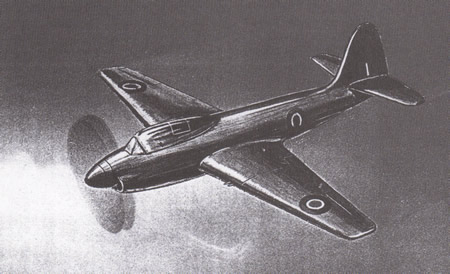

Fairey’s

Strike Fighter Concept: 1944

Raul Colon

May 5th. 2009

Email:rcolonfrias@yahoo.com

In late August 1944, the Fairey

Corporation was asked to asses the feasibility of adapting

its original tandem, twin engine research studies to a new

naval strike platform. The British Royal Navy issued a

verbal requirement statement in October asking for a twin

tandem aircraft fitted with a Tandem Merlin power plant,

codenamed Project A, and alternative Twin Griffon platform,

known as Project B. Either design was intended to be a

single seat fighter, although there was the possibility of

adding a rear compartment for a navigator.

The initial single seat platform design was very similar in

form to the Fairey’s O-21-44 Torpedo Bomber. The main

difference was a contra-rotating propeller system. Two heavy

calibre cannons were fitted underneath each wing nacelles,

the structure that also housed the main undercarriage. One

torpedo or a 2,000lb bomb load could be carried on the

plane’s centreline. The wings could also carry up to one

thousand pound bomb load under each inner wing.

Project A

was designed to carry a 300 gal fuel load internally and

additional 520 gal on drop fuel tanks. The plane's projected

top speed at a 20,000’ operational ceiling was estimated at

460 mph. Top service ceiling was 36,000’, but with a torpedo

load it fell to 29,600’. With drop fuel tanks, the aircraft

was able to operate at a distance of 820 miles. Project B or

Griffon carried a similar profile. Top speed was determined

at 397 mph with a top ceiling of 38,000’. Bomb load capacity

was the same as the A program. The only other variant visa-vise

the Merlin centred project was that the Griffon projected an

860-870 miles operational range, between forty to fifty

miles longer than the Merlin. Nevertheless, it was the

Merlin in which the company pitted their hopes for a new,

huge production contract. But the fact of the matter was

that Project A did not measure up to the concurrent Westland

N-11-44 design.

During the first weeks of March 1945, Fairey redesigned the

“A”’s overall specifications. The plane would still employ

the Merlin RM-17sm power plant, but the new version was

streamlined and compacted. The new concept was a welcome

sight to many inside the Ministry of Aircraft Production

(MAP) who were uneasy about the path the whole program was

taking. The new version of Project A had a better climb rate

than the Westland and a more robust undercarriage, a most

important consideration for naval operations. Still, the

Westland was considerably faster than the “A”. One factor

would change the dynamics of the “A”. By the middle of 1945,

engineers at Fairey and other British aircraft manufacturing

companies were adapting to a new kind of engine, the gas

turbine. The Merlin had achieved its peak of aerodynamic

design and now it was time to replace it with a more

flexible unit.

Fairey was quick to adapt to the new realities and promptly

began to design the “A” with a turbine propeller alignment.

With MAP consent, Fairley field officials commenced informal

discussion with Rolls-Royce engineers regarding the

availability of the Clyde engine as well as other jet

propeller gas turbine power plants under development.

Rolls-Royce gave the company advance data research

information for three top secret turboprop engines, RB-52

(an improved Clyde), RB-52-30 and RB-52-50. After

redesigning the “A” program with each of the three

prototypes, Fairey determined that the twin Merlin

configuration gave a better overall performance, thus

prompting the company to conclude that the expected high

cruising fuel consumption of the single turbine power plant

running in a throttle environment was the main culprit of

the “A” poor showing in contrast to the Westland. The

project managing team at Fairey decided to implement a small

twin turbine configuration which would drive a

contra-rotating propeller in a similar manner to the tandem

piston system. It was envisioned that this alignment would

give the “A” a better overall profile that a single turbine

of equal aggregate power.

Soon after the engine configuration decision was achieved,

the company commenced work on two new strike fighters. The

first would utilize a single RB-52-50 turboprop with a

contra-rotating propeller. The other example was fitted with

two B-52-30 arranged in tandem with a separated

contra-propeller gearbox with each propeller driven by its

own turbine system.

A

specification and profile paper was submitted to the MAP in

June 30th 1945 featuring three planes. Each had a 52 feet

wing span, four 20mm heavy calibre cannons and a torpedo

arrangement. The piston configuration (RB-52-30) offered a

total weight of 23,900lb, with a maximum speed of 410 mph at

a 10,000’ ceiling. The RB-52-50 weighted at 24,400lb with a

top speed of 395 mph and the same armament arrangement. The

Clyde’s profile was similar to the other two, only its

airspeed (413 mph) and total weight (23,300lb) was

different.

Following Fairey’s paper the MAP concluded that a single

Clyde system was inferior to the twin Merlin arrangement on

almost all areas. But the higher achieved power gave the

Project A an overall systematic quality that exceeded,

albeit not by much, the one profiled on the Westland (now

known as the N-11-44 project). The Admiralty gave the

company the official ‘go ahead’ to start pre-production

development on the strike fighter in September 1945. The

Royal Navy made it official on June 20th 1946 when it issued

Specification N-16-46.

With the end of the war in May 1945, the MAP began to review

all incomplete aircraft programs. All Rolls-Royce engines

designs were also reviewed. The company was asked to issue

its views regarding the standing of their twin-tandem piston

engine in regards to the new turboprops. In October,

Rolls-Royce stated that it was in favour of utilizing the

Fairey’s twin turboprop arrangement for navalized version of

the strike fighter project. At the same meeting, Rolls

executives told the Ministry members and Fairey senior staff

that eventually the company would shift its engine

developmental resources towards an axial flow jet engine.

Fairey got the message and abandoned its tandem system

altogether. Now, the company’s main military project would

be fitted with a side-by-side engine system housed behind

the main gearbox. Rolls accepted the idea and a new engine

system was born, call sign AP-25.

The changes to the engine system caused the alteration of

the original overall plane layout. The aircraft that emerged

after the redesign program was a much cleaner unit. It had a

completely clean trailing edge without hinge brackets, which

was a mainstay of Fairey’s recent designs. The wing

structure was laminated to allow an even air flow. The main

armament, the torpedo, was still housed on the airframe’s

centreline but now bombs, depth charges, rockets or any

supplemental weapon system would be carried under the wing

outboard of the main undercarriage between and below the

heavy cannon. The two side-by-side engine configuration

drove its own propeller through an independent mechanism

train carried by a central gearbox. The two jet pipes

exhausted through the bottom of the fuselage just behind the

wing area. Internal fuel capacity, with a torpedo profile,

was now 545gal. Top operational ceiling was estimated at

49,000’. There were plans to convert the Program A and B

into a single entity with a two-seated arrangement.

A complete aircraft layout was submitted to NE Rowe, the

MAP’s new Deputy of Development and Production on November

13th. Rowe accepted Fairey’s statement that Rolls would have

the new AP-25 engine ready for operational testing by

December 1946. On the morning of November 21st, Rowe advised

Fairey of a MAP amendment to the original specification

profile. The new order called for a true dedicated dive

bombing platform, instead of the strike fighter boxed role

first envisioned. On January 2nd 1946, the Admiralty issued

a new set of pre-production order for the aircraft with a

target date of January 1948. Immediately Fairey ran into

pre-developmental problems. First, the now dive bomber

proved to be too heavy for naval operations forcing the

engineering team to shed almost 1,000lb of weight, most of

them from the reinforced steel main fuselage. More

importantly to Fairey than the weight issue was the

development delays confronting Rolls Royce.

On October 17th, Royce executives advised their Fairey’s

counterparts on the delays facing the engine, now known as

Coupled Tweed, but still expected the power plant to be

ready by the following January. By early 1947, the Admiralty

was increasingly sceptic of the whole dive bomber/strike

fighter concept. Their top leaders could not cover the high

amount of monetary resources the Fairey platform was

‘eating’ yearly. For them, the time of the dive bomber has

log passed and on March 12th, it made it official with the

cancellation of the entire program.

For Royce, the termination of the project marked a shift in

the company’s priorities and investments. As for Fairey, the

company enjoyed a few success stories afterward. In the

months following the cancellation, the engineers that worked

on the strike program, as well as all the data collected on

it, was used on the Gannet Program.

Fairey Aircraft Since 1915, HA Taylor,

Putnam 1974

RAF Bomber Command and its Aircraft 1936-1940, James

Goulding and Philip Moyes, Ian Allan 1975

Planemakers II, David Monday, Janes 1982

|