equal

flying rights for women!

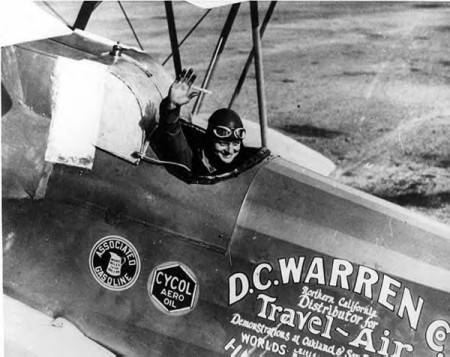

A

smiling Louise Thaden, December 1928, well-known female pilot.

Women gained the right

to vote in the United States in 1920. For the next decades, feminism moved

into a new stage, no longer focusing on suffrage. The new feminism focused

on individualism and on women proving they were men's equals by their

achievements. Actresses like Katharine Hepburn, athletes like Babe Didrickson, and artists like Georgia O'Keefe and Margaret Bourke-White

were examples. But it was the women in aviation who were the most daring

symbols of the new feminism, flying as high and as fast as the men, often

breaking records set by men and defeating them in races.

In the 1920s, the

organizers of cross-country air races did not allow women to compete. So

in 1929, the first All Women's Air Derby was organized to give women the

chance to prove they could fly the same course as men. But the all-male

organizing committee worried about women flying over the Rockies and

relocated the starting point to Omaha, Nebraska. The women rebelled and

the start was moved back to Santa Monica, California. Louise Thaden won

the race. But more importantly, the normally individualistic women had

discovered a sense of fellowship, which they wanted to foster.

Louise

Thadden waves from the cockpit of her Travel Air 4000 after setting the

women's endurance record with a time of 22 hours, 3 minute, and 28 seconds

in March 1929.

The women decided to

try to organize themselves. Four pilots, including Fay Gillis Wells, who

served as the temporary secretary, sent a letter to the 117 licensed

female pilots inviting them to help form a new organization. The letter

promised "not a tremendously official sort of organization, just a way to

get acquainted, to discuss the prospects for women pilots from both a

sports and breadwinning point of view, and to tip each other off on what's

going on in the industry."

Amelia

Earhart was the first president of the Ninety-Nines.

The organizational

meeting was held on November 2, 1929, in a hanger at Curtiss Field on Long

Island, New York. The 26 women present drank tea off a toolbox wagon and

debated names for their new organization such as the American Association

of Women Pilots, Ladybirds, Gadflies, and Bird Women. Amelia Earhart

recommended naming the group after the 99 women who replied positively to

the initial letter and who would be the organization's charter

members--The Ninety-Nines. Earhart was voted the first president,

reflecting the leadership role she had already unofficially assumed among

the women. The next morning, the New York Times reported on the meeting,

promising that "the women are going to organize. We don't know what for."

Louise

Thaden being congratulated for her first-place finish in the 1929 Women´s

Air Derby.

From the beginning,

the women were dedicated to increasing membership and promoting women in

aviation. Earhart encouraged the women to increase their visibility as

pilots by creating the Hat of the Month Club, which awarded a Stetson hat

to the member who had flown into the greatest number of airports that

month. But during the early years, the Ninety-Nines was an informal

organization with a newsletter and a get-together centred around the

Women's Air Derby (popularly referred to as the Powder Puff Derby). Most

of their early activities were associated with races since, although

organizers began to allow the women to compete, the women were restricted

from equal competition with the men by the rules. For instance, women were

limited to less powerful planes (an "appropriate" horsepower) and required

to take a male medical representative on the flight.

A large

crowd was on hand in Cleveland to witness the finish of the first Women´s

Air Derby.

The Ninety-Nines also

worked to have the first female medical examiner appointed at the

Department of Commerce and pressured the government to reconsider its

proposed ban on flying during menstruation. It was felt that a woman's

ability to fly decreased during these few days of the month. The

government agreed not to institute the ban, but doubts about menstruating

women's ability to function continued and often impeded their progress,

especially in the early days of the space program.

The Ninety-Nines lost

one of its first battles when Helen Richey, the first female commercial

airline pilot, resigned because of ostracism and pressure from her male

peers, despite support from the organization. The Ninety-Nines lobbied the

government to ignore the demands of the male pilots to increase

restrictions on female commercial pilots, but Richey gave in to the

pressure and resigned.

In the early days of

flight, knowing one's location was a major problem for pilots. Navigation

instruments and radios were not generally available to civilian pilots,

charts weren't reliable, and the airways system had not yet been

established. In 1934, Phoebe Omlie was named Special Assistant for Air

Intelligence of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Using her

influence within the government, funds from the WPA (Works Progress

Administration), and labour from the Ninety-Nines, she organized the Air

Marking Project. Under the program, states were divided into sections of

20 square miles (52 square kilometres). In each area, visible from the

air, a marker with the name of the nearest town was painted on the roof of

a prominent building and, where there were no buildings, ground markers

were made out of stone or brick. The National Air Marking Program was the

first government program conceived, planned, and directed entirely by

women. The program was a success and, with the exception of World War II

when the markers were removed in case of enemy invasion, the program

continues today as a central program of the Ninety-Nines, now mainly at

airports. It is a popular activity and a valuable aid to pilots.

During World War II,

the Ninety-Nines went to war. They served in the Women's Auxiliary

Ferrying Squadron and the Women's Airforce Service Pilots, organized by

Jacqueline Cochran, president of the Ninety-Nines throughout the war.

Pilots with nursing backgrounds pioneered the field of flight nursing.

Member Ruth Cheney Streeter became the head of the Women's Marine Corps.

Civilian members served as flight instructors, air traffic controllers,

and commercial airline pilots.

Helen

Richey was the first female commercial airline pilot. She was ostracized

by her male peers and eventually resigned.

When the war ended,

women everywhere were expected to return to their previous lives. The

Ninety-Nines were no exception, ignoring the enormous changes in these

women's lives and attitudes. They revived races, organizing the All Woman

Transcontinental Air Race, which was held annually from 1949 to1977. The

monthly magazine ran articles on fashion and cooking.

But that was not what

most women pilots wanted. The war had made flight training accessible to

women across economic and racial lines, and these women wanted to pursue

aviation as a career, not a hobby. Yet the Ninety-Nines continued on their

previous path, seen from the outside as society ladies in white gloves

without financial worries. Throughout the 1950s, their membership

decreased while the younger women pilots looked elsewhere for support in

their battle for careers in aviation.

Jackie

Cochran was president of the 99s throughout World War II.

But by the 1960s, the

Ninety-Nines began to refocus and address the realities of women's needs

in aviation. They supported many humanitarian projects, including an

informal program of ferrying medical supplies across North America. With

programs like the Amelia Earhart Scholarship, they created scholarships to

help women learn to fly, pursue advanced flight training, and to encourage

them to enter engineering programs. In the 1980s, in conjunction with the

FAA, the Ninety-Nines organized an intensive aviation safety program. They

also sponsor more than three-quarters of all pilot safety programs

annually. Individual Ninety-Nines chapters sponsor Wing Scouts units, the

aviation program of the Girl Scouts and Guides. Today, the Ninety-Nines

serve as a professional resource for women working in aviation, working to

ensure the maintenance of the economic status of these women. And ever

since Rosemary Conatser and her five classmates became the first female

military aviators with the Navy in 1974, the Ninety-Nines have been

involved in decisions governing women in the armed forces.

In 1991, astronaut and

Ninety-Nine member Eileen Collins ventured into space, carrying Louise

Thaden's cloth flying helmet, signed by the racers of the 1929 Powder

Puff. Derby. The connection between the past, present, and future,

encouraging fellowship and support, has remained strong, moving more women

to fly as high as they want, unimpeded by the restrictions of gender.

|