|

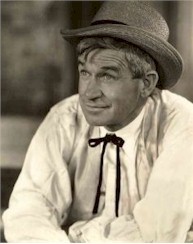

Wiley Post

Wiley Post and the Vega

Because of the records set by Wiley Post in the

Lockheed Vega, the plane became a

favourite of distance fliers and

record breakers, and for the most part these planes

were available to any

enthusiast. Wiley Post was born in

Texas, but his family moved to Oklahoma when he was

five and he was considered

an Oklahoman his entire life.

He

began his aviation career in 1924 at the

age of twenty-six as a

parachutist for a flying circus, Burell

Tobbs and His Texas Topnotch

Fliers, and was soon a

well-known performer on the barnstorming circuit. Post

injured his left eye in an

oil field accident, and when it

seemed that an infection might spread to both eyes and

deprive him of vision entirely, he had a surgeon

remove his left eye. The gamble

worked and he recovered normal

sight in his right eye, but wore a patch over his

false eye.

He took the money he received from

the workman’s compensation for the accident and bought an

old Canuck and repaired it

himself. In 1927, Post became the

personal pilot of oilman F.C. Hall. In 1928 Hall, desiring a

closed-cockpit plane, sent Post to the Lockheed factory in

Burbank, California, to buy the best one the company

produced.

Wiley Post with the Vega

Post selected the Vega, and Hall named the plane

the Winnie Mae, after his daughter. After Hall suddenly sold

the plane back to Lockheed during a downturn in business,

Post went to work for Lockheed as a salesman and test pilot.

When Hall was again able to purchase a plane and hire a

pilot, in 1930, he bought a new Vega (again calling it the

Winnie Mae) and rehired Post, this time with the intention

of letting Post carry out his plans for long-distance

flights. Post won the 1930 Men’s Air Derby, a race from Los

Angeles to Chicago that kicked off the National Air races.

For the race, Post had Lockheed install a

new Wasp engine capable of producing 500 horsepower. He used

the Derby to test the plane and some modifications that he

had made to raise its top speed to nearly two hundred miles

per hour (322kph). He was ready to tackle the record for a

round-the-world flight. Like most aviators, he was irked by

the fact that the record for flying around the world was not

held by an airplane, but by the Graf Zeppelin, which had

been piloted by Hugo Eckener in a 1929 record-setting global

circumnavigation of twenty-one days. Post engaged a marine

navigator, Harold Gatty, for the flight. Gatty had developed

several new navigational devices, including a combined

ground-speed and wind-drift indicator. This was particularly

important for Post because having only one seeing

eye

meant he lacked depth perception,

which made it difficult for him to

gauge distances and speed.

Post and Gatty took off from Roosevelt Field on June

23, 1931, and circled the globe west to

east in just eight days,

fifteen hours, and fifty-one minutes. (Naturally,

they titled their memoir of

the flight Around the World in

Eight Days). They would have done better, but several

times the Winnie Mae became

stuck in soft sand or mud and the

plane had to be moved to a new surface

for takeoff. In Edmonton, the plane was moved to a

main street where it took off with

a clearance of only inches for the

wings. This was an astounding feat, and in

appreciation Hall made a

present of the plane to Post.

The reception Post and Gatty

received after their record flight rivalled

Lindbergh’s everywhere they

went. With other fliers attempting

to break his record, Post

immediately planned a new flight

that he believed was well beyond

the capabilities of any other flier: a solo

flight around the world. On

the face of it, this should not be

more difficult than flying with a navigator since in neither

case is anyone other than the pilot flying the plane.

But not having a navigator puts an

enormous strain on the

pilot, who has to take readings and determine position while

flying the plane.

In an odd way,

Post’s injury actually helped him

because he was accustomed to making

calculations in his head all the time while flying,

to compensate for his lack of

depth perception. (He would

often say that he would have to give up flying if

they ever changed the height of

two- story buildings.)

As he had for his flight with Gatty, Post trained

like an athlete for the flight,

becoming accustomed to taking

short naps instead of sleeping through the night, and

learning to

focus his mind exclusively on flying. Post also

had two new devices that would help him

immeasurably: the automatic

pilot and a homing radio receiver, both

used for the first time on

this record-setting flight.

The automatic pilot, developed by

the Sperry Gyroscope Company, had

expanded the technology developed

by Jimmy Doolittle’s “blind

flights” of 1929 to include a

servo-mechanism that adjusted the

controls whenever the aircraft was

out of trim or was rotating around any axis.

Its main use was to allow the aircraft to cruise

automatically while the pilot attended to the

navigational chores.

Natives of Flat, Alaska, helping right Wiley

Post's plane, the Winnie Mae, after Post had nosed over in a

cross wind July 20 after being in the air 22 hours and 32

minutes on his flight from Khabarovsk, Siberia. The only

damage was a broken propeller, and a new one was brought to

Flat by Joe Crosson, pioneer Alaska flier. The new propeller

installed, Post continued his flight to Fairbanks.

Although only an early prototype of the device existed,

Post convinced Sperry to test it on the

Winnie Mae. The other

device allowed a pilot to determine the direction a radio

signal was coming from. This

device was developed by the U.S.

Army, which was eager to test it;

Post was happy to oblige. By the

time Post took off from Floyd

Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York, on

July 15, 1933, his main

challenges Jimmy Mattern, had

dropped out. But in spite of his

rigorous training and the

technological improvements, Post, who had seemed none the

worse for wear

after his earlier flight with Gatty, looked weary

and exhausted when he landed at Floyd Bennett

Field on July 22, to the

cheers of the 50,000 New Yorkers there to

greet him.

Post had circled the globe

in an astounding seven days,

eighteen hours, and forty-nine minutes,

more than twenty-one hours

faster than his record pace in the

flight with Gatty. Post credited the

automatic pilot, but the

fact was that the device did not work through much of the

flight and had to be

repaired several times. Post encountered more difficulties

on this flight than on the first

one, but he made up for lost time

by cutting down on his sleep—he

slept all of twenty hours during

the entire flight.

It was a feat

that fliers to this day find unbelievable.

Post then considered

entering the MacRobertson Race

between England and Australia held in 1934. He believed

the race could be won by

flying very high, say above thirty

thousand feet (9,144m), and for extended

periods, to take advantage

of one-hundred-mile-per-hour winds

in the upper atmosphere.

Wiley Post's pressure suit allowed him to cruise for long

distances at high altitude in the jet stream, and was a

precursor to modern pressure and space suits

Post designed

a pressurized suit that would allow him to fly at

forty thousand feet (12,192m) for

long periods, but the

Winnie Mae was now obsolete and Post decided

not to enter the

MacRobertson Race. Instead, he worked with

Lockheed designers to produce a hybrid plane that

combined the wings of an Orion with the fuselage of

an Electra. He hoped to set new

altitude and speed records

with the craft. In 1932

Post met the famous humorist (and fellow

Oklahoman) Will Rogers and

the two became close friends.

Rogers often flew with Post as a passenger and

he contributed an

introduction to the book Post had done

with Gatty about their flight. In 1935,

looking for new material

for his newspaper column, Rogers asked Post if

they could fly to Alaska.

This is the Lockheed-Orion Model 9E Special, NC122823,

formerly owned by TWA, that was modified by Wiley Post for

his trip to Alaska. Among other modifications, Post replaced

the engine with a 550 horsepower type, installed a

three-bladed variable pitch propeller, swapped out the wing

with one that was six feet longer from a Lockheed-Explorer

Model 7 Special, NR101W, that had fixed landing gear, and

then replaced the landing gear with floats

Wiley Post and Will Rogers during their fateful trip to

Alaska. Post never wore a hat

Post went to Lockheed and asked

the engineers to add pontoons to the Orion-Electra -

aircraft, but they refused,

telling him that pontoons would

upset the aerodynamic of the plane. Post

(believing -Rogers’ weight would compensate) had

pontoons placed on the plane

himself and flew Rogers up to

Alaska. On August 15, the fears of

the Lockheed engineers were realized and the

plane stalled while taking off from a lake

near Point Barrow. Post and Rogers died in the crash

sending the nation into mourning for two of its most

popular cultural heroes.

The last photo taken on August 15, 1935

Will Rogers

last farewell

The wreckage of Will Rogers' and Wiley

Post's Lockheed Orion-Explorer, after it crashed at Point

Barrow, Alaska in fog due to engine failure. Both men were

killed instantly

|