Howard

Robard Hughes Jr. (1905-1976) was arguably the most

secretive and self-destructive man ever to win fame in

Southern California’s two glamour industries --- movies and

aviation. Hughes was certainly an original, and to

many he represented the ultimate unconventional man.

The peaks and valleys of his life were startling. As an

aviator, he once held every speed record of consequence and

was hailed as the world’s greatest flyer, "a second

Lindbergh." At various points in his life he owned an

international airline, two regional airlines, an aircraft

company, a major motion picture studio, mining properties, a

tool company, gambling casinos and hotels in Las Vegas, a

medical research institute, and a vast amount of real

estate; he had built and flown the world’s largest airplane;

he had produced and directed "Hell's Angels," a Hollywood

film classic.

Yet by the time he died in 1976, under circumstances that

can only be described as bizarre, he had become a mentally

ill recluse, wasted in body, incoherent in thought, alone in

the world except for his doctors and bodyguards. He had

squandered millions and brought famous companies to the

financial brink. For much of his life, he seemed larger than

life, but his end could not have been sadder.

Hughes was born in Houston, Texas, (some historians say

Humble, Texas, the son of a flamboyant oil wildcatter,

Howard Hughes Sr. Four years after Hughes Jr.’s birth, his

father patented a rotary drill bit with 166 cutting edges

that penetrated thick rock, revolutionizing oil drilling

worldwide. Hughes Sr. and a partner formed what would become

the Hughes Tool Company and began leasing the rotary bits to

drillers for as much as $30,000 per well. They also bought

up patents for other rock bits and devised new drills for

the oil industry. The Hughes family was now wealthy.

Hughes Jr. grew up an indifferent student with a liking for

mathematics, flying, and things mechanical (he once built a

motorcycle from parts taken from his father’s steam engine).

He dropped out of Rice Institute in Houston and, through his

father’s influence, audited math and engineering classes at

Caltech in Pasadena, Calif.

Upon his father’s death in 1924, the 18-year-old Hughes

inherited an estate valued at almost $900,000, including 75%

of Hughes Tool Company, whose control he assumed a year

later. As Otto Friedrich writes in City of Nets, a book

about Hollywood in the1940s: "So it was the Hughes Tool

Company’s control of an indispensable oil drilling bit that

enabled Howard Hughes to imagine himself one of the kings of

Hollywood. No matter what he did, no matter how much money

he wasted, the Hughes drilling bit would always pay his

bills, would always protect him from harm."

Although shy and retiring, Hughes became enamoured with the

motion picture industry and moved to Los Angeles in 1925.

The city was already the world capital of film production.

Hughes financed three films of varying quality (one of them

won an Academy Award for director Lewis Milestone) before

undertaking an epic movie about Royal Air Force fighter

pilots in World War I. The film was "Hell’s Angels," which

Hughes came to direct as well as produce.

Undeterred

by the cost, he acquired the largest private air force in

the world -– 87 vintage Spads, Fokkers and Sopwith Camels -–

for $560,000, then spent another $400,000 to house and

maintain them. He even bought a dirigible to be burned in

the film. Hughes personally directed the aerial combat

scenes over Mines Field (what is now LAX). Three stunt

pilots died in crashes during the filming; Hughes also

crashed in his scout plane and was pulled unconscious from

the wreckage, his cheekbone crushed. With expenses already

exceeding $2 million, Hughes was forced to re-shoot large

segments of the film with dialogue to accommodate the advent

of talking pictures. And because the female star, Greta

Nissen, spoke with a thick and inappropriate Norwegian

accent, Hughes cast about for a replacement, finally

deciding on a bit actress with platinum blonde hair named

Harlean Carpenter, also known as Jean Harlow, the first

Hollywood "Blond Bombshell."

scene from Hell's Angles

The film

cost Hughes $3.8 million, a record for the time. Released in

1930, "Hell’s Angels" was a runaway success and set box

office records, but it never recovered its costs. ("Hell’s

Angels" is now regarded as a Hollywood classic. Among the

other films made by Hughes, two receive high marks from

critics -- "The Front Page" and "Scarface." His most

sensational film, "The Outlaw," starring Jane Russell, was

described as "more to be pitied than censored.") In their

1979 book, Empire: the Life, Legend and Madness of Howard

Hughes, Donald L. Bartlett and James B. Steele summarize the

typical Hughes movie as "rich in entertainment, low on

philosophy and message, packed with sex and action."

A boyish Hollywood legend, these were halcyon years for

Howard Hughes. As Otto Friedrich writes in City of Nets: "No

photographic record of that period would be complete without

a picture of the tall, scarred and inarticulate millionaire

ambling into some neon-lit nightclub, outfitted in

Hollywood’s black-tie uniform and displaying a beautiful

blonde on his elbow." Hughes kept company with such stars as

Ava Gardner, Katherine Hepburn, Ginger Rogers, Terry Moore

and Lana Turner, who once described him as "likable enough

but not especially stimulating." (He eventually married, and

divorced, actress Jean Peters.)

Throughout his Hollywood years, Hughes maintained his

passion for flying. Like the movies, aviation was booming in

Southern California, making the region a centre for new

technology. Hughes was in the thick of it, but unlike other

aircraft entrepreneurs, he preferred spending his time in a

cockpit rather than a boardroom.

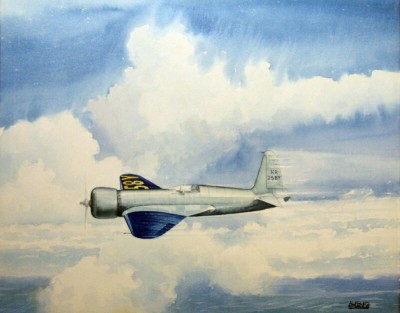

In 1934 he

won his first speed title flying a converted Boeing pursuit

plane 185 miles per hour.

Howard

Hughes poses next to the red H-I aircraft in which he set

the trans-continental speed record

in January 1937

He and a

young Caltech engineer, Dick Palmer, then built a plane

called the H-1 (featuring a unique retractable landing gear)

which Hughes piloted to a new speed record of 352 mph near

Santa Ana, Calif. This was in 1935, the year that Hughes

founded Hughes Aircraft Company as a division within Hughes

Tool Company, operating out of a hangar in Burbank, Calif.

In 1935 he

equipped a Northrop

Gamma H-1 with the

newest 1000-horsepower Wasp engine, and broke the old

air speed record of 314.3

miles per hour (505.Skph) by

thirty-eight miles per hour (6lkph). On June 14, 1936,

Hughes set a transcontinental speed record by flying

from Los Angeles to Newark Airport in nine

hours and twenty-seven

minutes, heating Roscoe Turner’s 1934

record by two full hours.

Hughes (in flight

cap) inspects the plane after a 1935

mishap in which he was forced to land with the

retractable landing gear locked in the closed

position. He had

earlier set a speed record of over 347.3 miles per

hour

In January 1937, after

further work on the Gamma H-1

(using the wind tunnel at Cal-Tech,

which he helped to fund), he cut

yet another two hours off his own record, crossing the

country in seven hours and

twenty-eight minutes. Aviation professionals

regarded the feat as reckless because he flew much of the

way at altitudes above fifteen thousand feet (4,572m)

without any special oxygen equipment. Hughes’ crowning

achievement came on July 14, I938, when he shattered

Wiley Post’s round-the-globe speed record by circling the

Northern Hemisphere (essentially Post’s route) in three

days, nineteen hours, and eight minutes (about half the

eight days Post needed). When Hughes’ Lockheed twin-engine

14-N Super Electra, which was equipped with two enormous

Wright Cyclone engines, the most powerful available, landed

at Floyd Bennet Field, a throng of twenty-five thousand New

Yorkers rushed onto the field to the plane to congratulate

him.

Upon

his return, Hughes was given a ticker tape parade down

Broadway in New York City. He was at the height of his

popularity.

Lockheed twin-engine 14-N Super Electra

The years of

World War II were frustrating years for Hughes, who hoped to

transform Hughes Aircraft into a major airplane manufacturer

after winning government contracts for two experimental

aircraft. All around him, Southern California aircraft

manufacturers were producing fleets of new planes. As it

turned out, Hughes Aircraft produced armaments, but not a

single plane for the war effort.

The United States government contracted

Howard Hughes to build a high altitude spy plane that could

go above radar with a special camera using newly developed

fine grain film. Howard was a pioneer of innovative ideas

such as the flat rivet to make aircraft more aerodynamic and

was always the test pilot in a new plane. The twenty-eight

cylinder engines in the XF11 developed more than enough

power to the counter- rotating double propellers designed to

create more thrust. Thirty minutes into the flight, the gear

boxes made for the propellers failed, leaving Hughes without

power and causing an out-of- control crash in Beverly Hills

which destroyed two homes. The wreck that he miraculously

survived left him scarred for life, addicted to morphine,

and a recluse.

Debris

from the crash of Howard Hughes' XF-11 reconnaissance plane

lies scattered between two houses damaged after the plane's

test flight on July 7, 1946. Hughes was seriously injured

when the landing gear jammed.

One contract

was for a photo-reconnaissance plane, a prototype of which

(the XF-11) crashed in Beverly Hills shortly after the war

during a test flight with Hughes at the controls, almost

killing him. The other contract was for a plane with which

Hughes is forever linked in the public mind -- a troop and

cargo carrier made of wood and known by various names (the

H-4 Hercules, the Hughes Flying Boat, the "flying

lumberyard"), but most popularly as the "Spruce Goose."

When Howard Hughes thought he thought big and he never

hesitated to take new directions. Conceived when German

U-boats were ravaging Allied shipping in the Atlantic, the

"Spruce Goose" was built primarily of birch -- not spruce -–

in response to a wartime metal shortage. It had eight

engines and the capacity to carry 700 troops or a load of 60

tons. In terms of wingspan (320 feet, which is longer than a

football field) and weight (400,000 pounds) it is still the

largest plane ever built. The war ended before it was

completed. But it was flown -- once -- in Long Beach Harbour

on Nov. 2, 1947.

Spruce Goose during its short flight

With Hughes

at the controls, the Flying Boat achieved a top speed of 80

mph, lifted 70 feet off the water, and flew a mile in less

than a minute before making a perfect landing. The plane was

then towed to a Terminal Island dry-dock, cocooned inside a

giant hangar, and never seen again by the public during

Hughes’ lifetime. Hughes’ Summa Corporation spent close to a

million dollars a year for the lease and maintenance. After

his death, the Flying Boat was put on exhibit in Long Beach

Harbour beside the Queen Mary; it has since been moved to

McMinnville, Ore., for display in an aircraft museum.

"It was as if he was missing the gene for corporate

success," write Bartlett and Steele in their biography of

Hughes. In 1948, he bought a controlling interest in RKO

Radio Pictures, which he almost brought to ruin with his

aberrant management style. He did much the same with Trans

World Airlines (TWA), whose controlling interest he bought

in 1939. Although he did much to transform TWA into a major

international carrier, his secretive ways and quixotic

decisions nearly plunged the airline into bankruptcy. In

1966 he was forced to sell his TWA shares after losing a

lawsuit that charged him with illegally using the airline to

finance other investments. The sale netted Hughes over half

a billion dollars. To many, it seemed more like a victory

than a defeat.

That same year, 1966, Hughes moved into the Desert Inn Hotel

in Las Vegas, which he proceeded to buy (rather than be

evicted), along with four other Las Vegas casinos, a radio

station, and other Nevada properties. He hired an ex-FBI

agent, Robert Maheu, to protect his privacy and keep him out

of court, even when his own legal interests were at stake.

He had become "the hermit gambling entrepreneur of Las

Vegas."

Even before moving to Nevada, while he was living at the

Beverly Hills Hotel, Hughes had exhibited alarming

behaviour. In 1958, he apparently suffered a second mental

breakdown, the first having occurred in 1944. Of his days at

the Beverly Hills Hotel, Bartlett and Steele write: "Hughes

spent almost all his time sitting naked in [his white

leather chair] in the center of the living room – an area he

called the ‘germ free zone’ – his long legs stretched out on

the matching ottoman facing a movie screen, watching one

motion picture after another." The same pattern was repeated

in Las Vegas, made worse by a drug habit that included both

codeine and Valium. (The codeine had first been prescribed

to alleviate pain from injuries incurred in the XF-11 plane

crash years earlier.)

Although Hughes managed to attend to business and had many

periods of lucidity (he held a telephone conference call

with reporters in 1972 to repudiate a book by Clifford

Irving purporting to be Hughes’ taped reminiscences), his

physical health had turned precarious. A doctor who examined

him in 1973 likened his condition to prisoners he had seen

in Japanese prison camps during World War II. That same

year, ironically, Hughes was inducted into the Aviation Hall

of Fame in Dayton, Ohio. He was represented by a member of

his 1938 around-the-world flight crew. One of the inductees

defended Hughes, calling him "a modest, retiring, lonely

genius, often misunderstood, sometimes misrepresented and

libeled by malicious associates and greedy little men."

In the final chapter of his life, Hughes left Las Vegas for

the Bahamas where he stayed until he moved to Mexico,

reportedly to have greater access to codeine.

(X-rays taken during the Hughes autopsy show fragments of

hypodermic needles broken off in his arms.) He died of

apparent heart failure on an airplane carrying him from

Acapulco to a hospital in Houston.

"Such was the mystery and power surrounding his life that

when he was pronounced dead on arrival at Methodist Hospital

in Houston, Texas, on April 5, 1976, his fingerprints were

lifted by a technician from the Harris County Medical

Examiner’s Office and forwarded to the Federal Bureau of

Investigation in Washington," write Bartlett and Steele.

"Secretary of the Treasury William E. Simon, for federal tax

purposes, wanted to be sure that the dead man was indeed

Howard Hughes. After comparing the fingerprints with those

taken from Hughes in 1942, the FBI confirmed the identity."

He had not been seen publicly or photographed for 20 years.

Howard Hughes’ greatest legacy to Southern California is the

family of Hughes companies founded during his lifetime.

These include Hughes Aircraft Co. (1935) and Hughes Space

and Communications Co. (1961), a unit of Hughes Electronics

Corp. Based in Westchester, Calif., Hughes Space and

Communications is the world’s largest manufacturer of

commercial satellites, the designer and builder of the

world’s first synchronous communications satellite, Syncom,

and the producer of nearly 40% of the satellites now in

commercial service. Hughes Electronics is owned by General

Motors. Hughes Aircraft merged with Raytheon Company in 1998

and is now called Raytheon Systems Co. Prior to the merger,

Hughes Aircraft was a world leader in high technology

systems for scientific, military and global applications.

All the technological prowess of these Hughes companies

would almost certainly have pleased their founder, who

always had a passion for building things.

It is possible the

Howard Hughes suffered from ADHD (attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder). He certainly suffered from OCD

(obsessive compulsive disorder) which is a common

co-morbidity to ADHD.

The Hughes H-1 replica prior to its fatal crash