|

Amelia Earhart

The stories and legends surrounding Amelia Earhart are

so ingrained in the American psyche

that one sometimes comes

away from reading about her with the feeling that

she is a fictional

character, a larger-than-life American

myth. She was, alongside Lindbergh (she was often

called “Lady Lindbergh”), the most

famous aviator of her time.

Amelia Earhart and husband George

Palmer Putnam, an influential

New York book publisher who made sure Earhart received

much—and

only the best kind of—publicity.

She virtually defined the strong presence women were

to have in aviation, even though

there were many great

women aviators before and since. Even during her

life-time, many of the same people

who idolized her regarded her as

an enigma; it is somehow fitting that her death

should constitute the

greatest and most enduring mystery

in the history of aviation.

Amelia Mary Earhart was born

in Kansas in 1897. In 1919 she

dropped out of Columbia University

and began doing secretarial work

in order to pay for flying lessons

with Neta Snook. The two women

became lifelong friends. Earhart’s

family’s fortunes declined in the mid-

1920s and she took

employment as a social worker in

Boston. In 1928 an extraordinary stroke of luck

put Earhart in a position

to be the first woman to fly the

Atlantic, albeit as a passenger.

Mrs. Frederick Guest of London

(née Amy Phipps of Pittsburgh)

bought Richard Byrd’s Fokker

Trimotor and renamed it the

Friendship. She intended to hire a crew to

fly her over the Atlantic,

but her family wouldn’t hear of

her taking such a risk. She insisted, however, that the

plane be used to fly an

American woman across the

Atlantic, and formed a committee to find the woman

who would take her place. On the committee was

George Putnam, publisher of such aviation

classics as Lindbergh’s We

and Byrd’s Skyward. Putnam asked a

friend if he knew of any likely

candidates, and he was told to

contact a woman working as a social worker at

Dennison House in

Boston.

He did just that and invited

Earhart to come to New York to be interviewed by the

committee. It was in New

York that she met George Putnam,

whom she married in 1931. The

committee felt they had found the

perfect replacement for Mrs. Guest. Earhart was attractive

in an artless way,

her tousled hair and boyish looks radiating a kind

of purity that betrayed her Midwestern origins.

Yet she spoke emphatically

and with a clear sense of independence.

She was told that

she was simply going to be a

passenger on the flight, and that the plane would be

piloted by veteran pilots

Wilmer Stultz and Louis “Slim”

Gordon. She asked whether there might come a time

when she would be able to

take the controls, however

briefly; she was told perhaps. On

June 3, 1928, she secretly climbed

aboard the Friendship in Boston

for the first leg of the trip, to

Newfoundland. A sailor in the harbour spotted her, however,

and by the time the plane took off for

Ireland on June 17, the

word was out that a woman was in the

process of crossing the Atlantic

by airplane for the first

time.

Amelia Earhart’s orange

and silver Lockheed

Electra soars over the

Golden Gate

Bridge as it heads

toward Honolulu on

the first stage of

her first attempt at a

round-the-world

flight in 1937

Amelia Earhart’s orange

and silver Lockheed

Electra

When the plane landed in Wales (having overshot

Ireland in the fog), the plane had been in the

air twenty hours and forty

minutes, and a great throng was ready to

meet her. Earhart became

world-famous, even though some

women criticized her for accepting such a passive

role on the flight. The

fact was that Earhart simply did

not have experience with multi-engine planes, and

another woman, Mabel Boll, was arranging to pilot a

flight at the very time Earhart took off as a

passenger.

In the years that followed, Earhart made a determined

effort to prove her piloting skills and to

show the world that she

could have flown the Friendship across the

Atlantic. She worked to

promote women’s aviation and

became an eloquent and forceful proponent of including

women in exhibition and

racing events. Although both men

and women pilots questioned Earhart’s flying

abilities throughout her life, she proved her mettle

in dozens of flights and in

setting many records.

On May 21, 1932, Earhart flew a Lockheed Vega solo

across the Atlantic, from Newfoundland to

Northern Ireland. The

flight encountered serious obstacles—a

storm, a troublesome leak in the

engine, a broken altimeter—and only a flier of skill

would have made it. Later in the

year, she set women’s distance and

speed records when she became the

first woman to fly solo non-stop

cross the United States. A series of trans-Pacific flights

brought her fame, but her most

important flying achievement was probably her solo

flight from Hawaii to San

Francisco in January 1935—she was

the first person to make the

flight, after many others had failed.

Amelia Earhart’s Vega

After Wiley Post’s two flights around the world, aviators

began looking forward to someone

attempting a round-the-world

flight along a route closer to the equator. Post had skirted

the North American and Eurasian

continents, which was not strictly a round-the-world

trip. Earhart

assembled a flight team consisting of two

pilots—herself and Paul Mantz—and two navigators:

Fred Noonan, Pan Am’s chief navigator, and Harry

Manning, a highly regarded maritime

navigator. She also

arranged with the Lockheed Company that she be lent an

Electra for the flight.

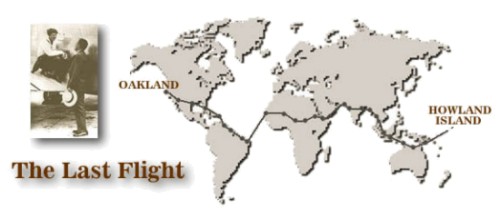

On March 17, 1937, Earhart and crew took off from

Oakland, intending to head westward and

cross the Pacific for the

first leg of the flight. It is not known

exactly what had happened, but the

plane tilted and a wing

scraped the ground. By the time the plane was

repaired, only Noonan

remained of the original crew.

Since he was very familiar with the Caribbean from his

work for Pan Am, the flight

would now originate from Miami and

head eastward. The plane took off on

June 2 and headed out

across the Atlantic, staying just a few

miles from the equator.

The flight across the South

Atlantic, Africa, and the Asian

subcontinent went smoothly. The

plane took off from Lae, New

Guinea, on July 2, heading for a stop on

Howland Island, about a

third of the way to Hawaii. What

happened next has been the subject of investigation and

for more than fifty

speculation years. The

plane certainly

went down at a location other than

Howland Island. It does not

seem reasonable to assume that the plane put

down at sea since no

floating wreckage was ever found. If

the plane landed on an island in the vicinity,

because it was lost or experienced

some mechanical failure, then the most

likely landing place would have been

Gilbert Island, then under

Japanese control.

| Date |

Departure |

Arrival |

Distance

(nautical miles) |

Notes |

| May 21 |

Oakland, California |

Burbank, California |

283

|

. |

| . |

Burbank |

Tucson, Arizona |

393

|

. |

| . |

Tucson |

New Orleans,

Louisiana |

1,070

|

. |

| . |

New Orleans |

Miami, Florida |

586

|

final servicing of

plane |

| June 1 |

Miami |

San Juan, Puerto Rico |

908

|

June 3 photo taken at

S.J.? |

| . |

San Juan |

Cumana, Venezuela |

492

|

. |

| . |

Cumana |

Paramaribo, Suriname |

610

|

. |

| . |

Paramaribo |

Fortaleza, Brazil |

1,142

|

. |

| . |

Fortaleza |

Natal, Brazil |

235

|

. |

| . |

Natal, Brazil |

St. Louis, Senegal |

1,727

|

translantic leg, 13

hours, 12 min. flight time |

| . |

St. Louis, Senegal |

Dakar, Senegal |

100

|

. |

| . |

Dakar |

Gao, Mali |

1,016

|

. |

| . |

Gao |

N'Djamena, Chad |

910

|

. |

| . |

N'Djamena |

El Fasher, Sudan |

610

|

. |

| . |

El Fasher |

Khartoum, Sudan |

437

|

. |

| . |

Khartoum |

Massawa, Ethiopia |

400

|

. |

| . |

Massawa |

Assab, Ethiopia |

241

|

. |

| . |

Assab |

Karachi, Pakistan |

1,627

|

first flight from

Africa to India |

| June 16-17 |

Karachi |

Calcutta, India |

1,178

|

. |

| . |

Calcutta |

Sittwe, Burma |

291

|

. |

| . |

Sittwe |

Rangoon, Burma |

268

|

. |

| . |

Rangoon |

Bangkok, Thailand |

315

|

. |

| . |

Bangkok |

Singapore |

780

|

. |

| . |

Singapore |

Bandung, Indonesia |

541

|

delayed here by

monsoon |

| June 27 |

Bandung |

Surabaya, Indonesia |

310

|

. |

| . |

Surabaya |

Kupang, Indonesia |

668

|

. |

| . |

Kupang |

Darwin, Australia |

445

|

. |

| June 28-29 |

Darwin |

Lae, New Guinea |

1,012

|

direction finder

repaired, parachutes sent home |

| . |

Lae |

Howland Island

|

2,224

|

never arrived |

| . |

Howland Island

|

Honolulu, Hawaii |

1,648

|

. |

| . |

Honolulu |

Oakland,

California |

2,090

|

. |

| . |

|

Total Miles |

24,557 |

. |

|

Relations between the United

States and Japan were already

strained during this period, and

if, as some Lockheed employees said, spy

cameras were mounted on the

Electra for photographing the

Japanese, then Earhart and Noonan

might have been thought to he

spies and eliminated. The search

lasted two weeks and involved

hundreds of naval vessels and

aircraft, as well as hundreds of personnel, hut nothing was

found (though search parties could

not land on Gilbert Island). In the years since, many

theories have been propounded

about the fate of Amelia Earhart.

Many natives of the South Pacific have

testified that they

saw Earhart a prisoner of the Japanese or that

they saw a photograph of her

amid Japanese boats or soldiers.

Whatever the truth, her disappearance marked the

untimely end of a career that promised to inspire

many women to take active roles in

many facets of American society,

not just in aviation. It is probably true

to say that her career was somewhat a triumph of spin over

actual aviation skill. There were many women aviators who

were every bit as equal to the best men of the day but they

lacked the newspaper backing that George

Putnam was able to provide. She had an unshakable belief

that 'good luck' would take her through. The choice of a

well known alcoholic as navigator on her last flight

challenged this belief one step too far.

|