|

Calbraith

Rodgers

Calbraith

Rodgers

Before 1911 Calbraith P. Rodgers was not well known in

aviation circles and, if the truth be

known, he was never

considered a very accomplished flier. When he took off

from Sheepshead Bay, New

York, attempting to fly to the

California coast in thirty days, aiming to win a prize of

fifty thousand dollars offered by William Randolph

Hearst, few people gave him much chance of

even completing the flight, let alone doing so in the

stipulated time.

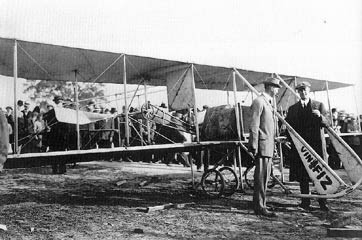

He flew a Baby

Wright plane that was prone to

stalling even in the hands of a good pilot. The plane

was called the Vin Fiz,

after the grape-flavoured soft drink produced by the

Armour Company, which sponsored the

flight. Rodgers’ route took

him from New York to Chicago, then

down to San Antonio, Texas, and

finally along the southern border

of the United States to Long

Beach, California.

Vin Fiz

This allowed him

to avoid the mountains entirely, a barrier Rodgers

was not equipped (by machinery or

skill) to hurdle.

During the flight, Rodgers made sixty-nine stops,

sixteen of which were crash landings.

(Rodgers refused to admit

it, but there was no question that he had trouble

landing.)

In between crashes!

Each crash

landing necessitated repairs, and the

times he landed without crashing, people flocked to

the plane and grabbed a souvenir,

usually a vital piece of the

aircraft. Fortunately, Rodgers was not alone.

He followed railroad tracks and

below him was a private train paid

for by Armour, on which were

machinists, Rodgers’ wife and

mother, and enough spare parts to build four complete

airplanes just like the Vin Fiz.

It turned out that he needed those

parts, because only two parts of the

original plane he took off

in were still on the craft he flew into

Long Beach on November 5.

Rodgers completed the four thousand-mile (6,436km)

flight in fifty days, too late to win the

Hearst money, but Armour

rewarded him with a prize of their own of more

than twenty thousand

dollars. He became celebrated

through the posters and advertisements Armour produced

commemorating the flight, but the most remarkable

aspect of it, aside from his perseverance,

may have been simply his

having lived though all those crashes.

In April of 1912, Rodgers died in

a crash as the plane he was flying

in an air show plunged into the

Pacific off the coast of Long

Beach. Observers thought he may have

been attempting to land

when the crash occurred. Rodgers

paved the way for the first non-stop coast-to-

coast flight, made on May 2

to 3, 1923. Flying a single-

engine Fokker 1-2, powered by a Liberty engine, the

U.S. Army Air Service team

of Oakley G. Kelly and John A.

MacReady made the 2,650-mile

(4,264km) trip in just under

twenty-seven hours.

They flew from Roosevelt

Field on Long Island, New

York, diagonally across the

country, skirting below the Rocky Mountains and landing at

Rockwell Field near San Diego. Although they

arrived after midnight, a large crowd turned out to

greet them and newspapers

across the country hailed the feat

as the beginning of a new era. The

most direct consequence of the flight was that it prompted

the U.S. government to prepare for

a transcontinental airmail service,

inaugurated in July 1924.

Army fliers McCready and Kelly established

a new endurance record

by staying aloft for thirty-eight hours in a Fokker

monoplane, flying

near San Diego, from October 14 to 15, 1922.

|