|

Richard Byrd and

Floyd Bennett

Portrait of Richard Byrd.

Exploration of the uncharted areas of the globe by airplane

and airship became very active in the

1920s for a variety of

reasons. Looking forward to the establishment

of aerial transportation from

continent to continent, it

was necessary to know what aircraft were capable of,

whether aerial navigation

techniques were adequate, and

whether or not ground support could be provided en-route.

These reasons, combined with the general adventurousness

that pervaded the 1920s, led to

many path finding flights across

oceans and continents, but an

additional set of reasons came

into play in motivating aerial

exploration of the Arctic and Antarctic regions.

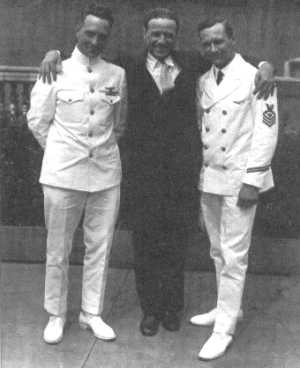

Three aviators pose at a dinner in their

honor at New York’s McAlpin Hotel. Known as “the three B’s of aviation,” they

are

Commander Richard E. Byrd (left) and Floyd Bennett (right)

in their

dress-white uniforms and Captain Homer M. Berry (Centre),

who was

already being feted as the pilot of the first New

York-to-Paris nonstop

flight, scheduled to take place some months in the future.

Berry was a

respected air hero of World War I, and there was little

doubt that he

would be the winner of the Orteig challenge. As it turned

out,

however, he was soon thereafter replaced as the pilot and

the aircraft

crashed on take-off

In the late twentieth century, it

is difficult to believe that as

late as the mid-1920s there was thought to be

land north of the Alaska in

the middle of the Arctic Ocean, in

an area known as the “blind spot,” in the middle of which

was the “Pole of Inaccessibility,” a point

equidistant from all land masses and

about four hundred miles

(643.5km) south of the North Pole. On official

charts, it was called Crocker Land or Keenan Land, and

appeared with question marks and purported outlines, arrived

at from unreliable sightings and calculations based on

measured anomalies of the currents passing through the

Bering Strait.

Three teams were deeply involved in the

aerial exploration of the Arctic: the Norwegians, led by the

famed explorer Roald Amundsen, who had

reached the South Pole over land in

1912; an American team headed

by Richard E. Byrd, a

lieutenant commander in the U.S. Navy; and a group

led by the Australian George H.

Wilkins, who sought and

accepted help from many sources.

First out of the gate was Amundsen.

After being forced

into bankruptcy in 1924 through mismanagement on the

part of a ship broker who had

failed to purchase planes for a

flight over the North Pole (after

all other provisions for the flight

were bought and paid for),

he teamed up with a wealthy

American who simply called him in

his New York hotel room

and offered to finance the expedition to

the North Pole, if he could come

along.

This was how Lincoln Ellsworth, by then a man of over

forty and with virtually no connection to

flying (he had flown some

in the war) and no Arctic experience, entered

the annals of Arctic aerial

exploration. Amundsen had the

resources now to purchase the

planes he needed. He and Ellsworth

acquired two Dornier-Wal all-metal

boat planes with two powerful

Rolls-Royce engines arranged in

tandem atop the wing. Amundsen and

Ellsworth took off in May 1925 in

two planes, the N-24 and the N-25,

each with a crew of three, from King’s

Bay, Spitsbergen.

Both planes were

forced down short of the Pole. In one

of the most dramatic feats of perseverance and

survival on record, all six

crew members managed to survive for

three weeks, repair one of the

planes (the N-25), and make

it back to Spitsbergen on June 15.

Amundsen and Ellsworth were

determined to try for the Pole again,

and in 1926 they purchased a semi-

rigid dirigible, the N-1,

from the Italian designer Umberto

Nobile. While they were preparing

the dirigible—renamed the Norge (or

“Norway”), much to the consternation of the Italians—for

flight, an American team arrived at King’s Bay.

Seen here is Lincoln Ellsworth, one

of the

great aviators in the grand tradition of

Arctic (specifically Alaskan) aviation.

The Americans had tried an over-the-pole

flight two years earlier, using three Loening amphibian

biplanes with open cockpits. The team, headed by Captain

Donald P. MacMillan and Richard E. Byrd, was sent by the

navy to find Crocker Land (or whatever was out there) and to

perform a flying feat that could diminish some of the lustre

of the army’s Douglas World Cruisers.

It was clear from the

start that the planes were not nearly durable enough,

especially not their landing gear, and MacMillan abandoned

the project. But Byrd and his very able pilot, Floyd

Bennett, sought private funding for another try. With the

help of Edsel Ford, Byrd purchased a Fokker Trimotor and

named it the Josephine Ford (much to Anthony Fokker’s

consternation). The third group to arrive in 1926 was headed

by George Hubert Wilkins, flying a Fokker Trimotor called

the Detroiter, and a single-engine Fokker called the

Alaskan.

He too had a talented pilot at his

disposal, a North Dakotan named Carl Ben Eilson who had

become the foremost Alaskan bush pilot. Wilkins was more

interested in exploring the “blind spot” than in making an

over-the-pole flight, hut the newspaper publishers who were

his hackers insisted that he try for being the first to fly

over the pole.

ABOVE: Flying over the Arctic was a

treacherous and dangerous undertaking.

Here, Amundsen (right) inspects the mono-plane in which he plans to attempt a fly-over of the North Pole; on the wing is his

mechanic, Oskar Omdal.

RIGHT After the

successful flight of Byrd and Bennett over

the Pole in 1926, the pair teamed up to

cross the Atlantic, but Bennett was injured

in the last test flight before the planned

attempt. Bennett (on crutches) is greeted by

Byrd in front of the America

Thus, as May 1926 dawned, the three teams

preparing to fly into the Arctic region were not really

competing with one another. The Detroiter was soon Out of

commission after its landing gear collapsed, and the

Alaskan, considered a hard-luck ship because a reporter had

been decapitated accidentally by the propeller, was not

powerful enough to make a polar flight. That left the field

to Amundsen and Byrd.

The newspapers promoted the notion that a

race was underway, but in fact, the two teams assisted one

another throughout the preparations. Bernt Balchen, a

Norwegian flier who had been sent to search for Amundsen

back in 1925 and who had become a close friend of Amundsen

and a valuable member of his crew, gave Byrd much advice

(with Amundsen’s blessing) on the best construction of

landing gear for the Arctic. Balchen would later be invited

by Byrd to join him in subsequent history-making flights.

(After Byrd’s death in 1957, Balchen claimed that Byrd had

not flown to the North Pole, but this claim was never

substantiated.) At 12:37 A.M. on May 9, 1926, Byrd and

Bennett took off in the Josephine Ford and flew toward the

North Pole. They reached the Pole (by Byrd’s calculations)

at 9:02 and circled for fifteen minutes taking pictures.

They had intended to return by way of

Cape Morris Jesup on the north-western corner of Greenland,

but an oil leak prompted them to take no chances and they

returned directly to Spitsbergen, arriving to cheering

Norwegians (and an uncharacteristically effusive Amundsen)

at 4:07 P.M. The Norge took off two days later, and while it

passed over the Pole and made it to Teller, Alaska, in just

under seventy-one hours, the flight was a torture to both

Amundsen and Nobile.

The two men were determined not to let

their countries be deprived of the honour that was due to

the nation that sponsored the first crossing of the Arctic

Ocean. Amundsen, a stoic, imperious-looking figure (hut by

all accounts a man of great warmth and humour), irritated

the excitable Nobile at every opportunity. None of the

crew of sixteen (and one dog) slept for the three-day

flight—the cabin was simply too cramped— but Amundsen

insisted on sitting in the only chair and mercilessly

needled Nobile and his Italian crew (who in truth knew much

more about dirigible flying than the Norwegians), believing

there was little point in even making the flight now that

Byrd and Bennett had reached the Pole.

It was considered the height of irony

when, in June 1928, Amundsen perished while flying a rescue

plane in search of Nobile and the !talia, a refitted version

of the Norge. Wilkins and Eilson returned to Alaska in the

spring of 1927 with two Stinson biplanes and attempted to

cross the Arctic from Point Barrow to King’s Bay. They

landed successfully and took off on the polar ice, the first

time an airplane had managed that feat, but they

crash-landed only sixty-five miles (104.5km) out of Barrow.

The fliers trekked over treacherous ice for more than

thirteen days, racing not only the cold, but the frostbite

that had set in to Eilson’s fingers and threatened to take

his entire arm if they did not reach help soon. They soon

made it to Beachey Point, an Eskimo trading post east

of Barrow, where Eilson was rushed to the hospital. (He lost

only One finger to the ordeal.)

A year later, Wilkins and Eilson were

back for another try. This time they flew one of the first

Lockheed Vegas produced. The plane performed excellently and

the flight, which began on April 15 and ended six days later

because of a five-day storm that the fliers waited out on

the ground, was hailed as one of the great Arctic flights of

the period. Wilkins was knighted and the pair became

international celebrities. Their flight had accomplished a

number of things. It demonstrated the capabilities of the

Vega, a plane that was to become a favourite of long

distance fliers for to years come. It put to rest once and

for all the notion that there was any land mass between

Alaska and the North Pole. And it demonstrated that

trans-Arctic flights might not be as dangerous as once

thought, which meant that great circle air routes from North

America to Europe and Asia should be seriously considered

for commercial aviation when planes improved.

Byrd received the Congressional Medal of

Honour for his Arctic flight (which makes Balchen’s later

claim all the more curious). Just as he had assisted the NC

aircraft crews and Alcock and Brown in their trans-Atlantic

flights, he provided navigational assistance to Lindbergh

for his historic 1927 flight. After a June 1927 flight

across the Atlantic with Balchen (Bennett was nursing a

broken leg at the time), Byrd turned his attention to the

Antarctic. By now an admiral and an international celebrity,

Byrd raised private funds with the help of Edsel Ford and

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and began a period of adventure

and exploration that captivated the world from 1928 to

the mid-1930s.

Flying the Fokker Trimotor Floyd Bennett,

named after his pilot (who died in 1928 of pneumonia,

contracted while on a rescue flight in Canada), with Balchen

and two other fliers, Byrd flew over the South Pole on

November 29, 1928, setting yet another milestone in polar

aviation.

|