Arctic Aerial

Exploration

Photo

shows the Curtiss Oriole Kristine presented to Arctic explorer Roald

Amundsen by Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Corporation, 1922.

Photo at top left is Lt. Oskar Omdal. Capt. Roald Amundsen as at the

right.

During the late 19th

century, many Americans and Europeans romanticized distant and unexplored

lands; the more exotic a place seemed, the more exciting it was. Africa

and the Arctic consequently captured people's attention. Although many

individuals had contemplated exploring the north polar region throughout

history, it was not until the late 1800s--after several scientific and

technological advances had taken place--that adventurers could mount

serious expeditions into the area. As explorers set out into the Arctic, a

major race began to see who could be the first to reach the North Pole.

Land-based expeditions got to the Pole first in 1909 (although some

scholars are still debating this "fact"), but another contest quickly

ensued among aviators to see who could be the first to fly to the "top of

the world." Pilots also began battling to see who could be the first to

soar across the entire width of the Arctic. In all, from the late 1800s to

the mid 1950s, several aviators competed to establish records in the

Arctic.

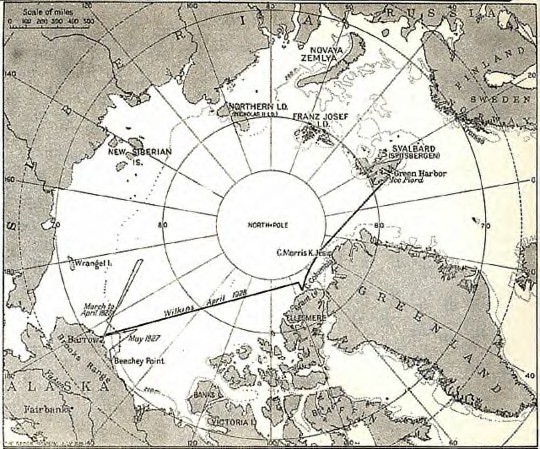

Polar

projection map of the Arctic Ocean, centered on the North Pole, showing

the route

of two flights of pilot Carl Eielson and George Hubert Wilkins over the

region.

Their aborted March 1927 flight (and route followed by foot back to

Alaska),

and their more successful April 1928 flight from Point Barrow Alaska, to

Dead Manīs Island

in the Svalbard Group, near Spitsbergen, Norway, are shown.

The first flight over

the Arctic occurred in 1897 when Swedish engineer Solomon Andree tried to

pilot a hydrogen-filled balloon from Spitsbergen, Norway, to the North

Pole. Andree lifted off on July 11 and reached almost 83° N latitude

before his balloon went down and he disappeared. It was not until 1930

that another team of explorers discovered his remains. Although Andree's

expedition failed, it did start others thinking about using balloons to

explore the polar region.

The first serious

attempt to use airplanes in the Arctic occurred in 1923 when Norwegian

explorer Roald Amundsen--who in 1911 had been the first person to reach

the South Pole--tried to fly from Wainwright, Alaska to Spitsbergen with

fellow Norwegian Oscar Omdal. Unfortunately, Amundsen and Omdal's aircraft

became damaged and they had to abandon their journey. Nevertheless, by May

1925, Amundsen was back at it again, this time with American explorer

Lincoln Ellsworth, and a small crew. On May 21, the group tried to reach

the North Pole using two Dornier Wal "flying boats." After taking off from

Kings Bay in Spitsbergen, they made it to approximately 88° N latitude

before making an emergency landing due to mechanical problems. Stranded,

they spent more than three weeks carving out a runway on the ice so that

they could takeoff and return home. Although the expedition ultimately

failed, it was the first attempt to fly an airplane to the pole.

Portrait of Richard Byrd.

A year after the

Amundsen-Ellsworth expedition, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander Richard Byrd

and pilot Floyd Bennett joined the ranks of those trying to reach the Pole

via the skies. On May 9, 1926, the two men took off from Kings Bay in a

trimotor Fokker aircraft and headed toward the top of the world. After 15

hours, 30 minutes (or 15 hours, 57 minutes, depending on the source), Byrd

and Bennett returned to Spitsbergen and claimed to have circled the North

Pole. Within the year, both men would receive the U.S. Congressional Medal

of Honour.

The

Josephine Ford, the plane that Richard Byrd flew to the North Pole on his

1926 polar expedition.

However, despite Byrd

and Bennett's apparent triumph, controversy quickly marred their feat.

Several people questioned whether they had even made the trip. Some

aviators doubted that the men could have flown that far given the trip's

short elapsed time and whether a trip that fast was within their plane's

capabilities, given its usual average speed. There are several other

reasons why some historians doubt whether Byrd and Bennett made it to the

North Pole, but generally, most people continue to regard them as the

first to fly over the top of the world.

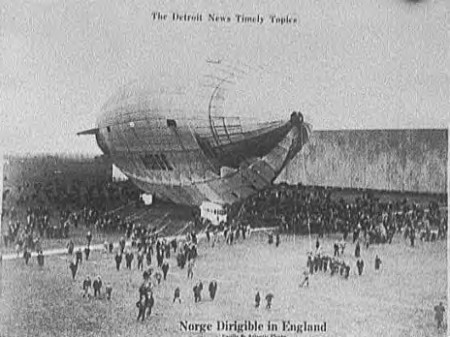

The

Norge dirigible in England.

Roald

Amundsen, somewhere in Alaska, around 1925.

Only a few days after

Byrd and Bennett returned, Amundsen and Lincoln Ellsworth boarded the

Italian dirigible Norge (meaning Norway) in Spitsbergen and headed for the

Pole. They had wanted to be the first to fly over "the top," but after

Byrd and Bennett's record setting journey, they could hope only to be the

first to fly over the Pole in a dirigible. On May 12 (or 13, depending on

which side of the globe and international date line one is on), the Norge,

piloted by Italian Umberto Nobile, crossed the Pole en route to Alaska.

The flight marked both the first dirigible journey over the Pole and also

the first crossing of the entire Polar Sea. It also enabled Amundsen to

become the first person to have visited both the North and South Poles.

The

Norge preparing for the second stage of its polar flight, in its hangar in

Pulham, England, 1924.

At approximately the

same time that the Byrd-Bennett and the Nobile-Amundsen-Ellsworth

expeditions were taking place, Australian adventurer George Wilkins joined

forces with Alaskan bush pilot Carl Ben Eielson and began a series of

attempts to traverse the Arctic Ocean in an airplane. They tried several

times in 1926 and 1927, but failed each time. Then, in April 1928, they

flew a single-engine Lockheed Vega from Point Barrow, Alaska, to

Spitsbergen. It was the first successful crossing of the Polar Sea in an

airplane. Both men became international celebrities. Wilkins received a

knighthood and became known as Sir Hubert, while Eielson claimed the

Harmon International Trophy for being the year's best aviator.

This

photo shows the flying boat used on Roald Amundsenīs North Pole expedition

on the return of the expedition to Oslo, Norway, in June 1925.

In May 1928, about a

month after Wilkins and Eielson's achievement, the first major Arctic

aerial tragedy occurred and claimed the lives of several polar explorers.

The incident began when Umberto Nobile and his crew attempted to fly a new

dirigible, the Italia, over the Arctic. Nobile and the Italia crashed

during the return journey and Roald Amundsen and several adventurers

immediately mounted the first significant Arctic aerial search and rescue

mission. Amundsen and his crew died when their plane went down during the

search. Even though Nobile and five of his crew eventually made it to

safety, some of the era's best polar explorers had died in the process.

In the 1930s and the

1940s, the Russians began to dominate Arctic aviation. On June 18, 1937,

pilot Valery Chkalov and two crewmembers flew a single-engine ANT 25

airplane from Moscow to Vancouver, Washington, via the North Pole. The

entire flight took 62 1/2 hours, some 5,500 miles (8,851 kilometres), and

established a new nonstop, long distance flight record. Within a month,

another three-man crew, led by Mikhail Gromov, piloted his ANT 25 to yet

another endurance record when they flew non-stop from Moscow to San

Jacinto, California, by way of the North Pole, a journey of some 6,300

miles (10,139 kilometres), in 62 hours, 20 minutes. Then, on April 23,

1948, three Russian aircraft carried several scientists to the North Pole

to establish a scientific base, landing at exactly 90° N latitude. It was

the first time that any aircraft had ever actually touched down precisely

at the North Pole. A year later, on May 9, two Soviet scientists set

another record when they became the first people to parachute onto the

Pole.

In the 1950s, two

Americans established a couple of important Arctic aviation records. On

May 29, 1951, U.S. Navy Captain Charles Blair flew a P-51 Mustang fighter

from Bardutoss, Norway to Fairbanks, Alaska, via the North Pole. It was

the first solo flight over the North Pole and the Arctic. The non-stop

journey had taken 10 hours, 27 minutes, and traversed some 3260 miles

(5,246 kilometres). Blair received the Harmon International Trophy for his

achievement. A few years later, in 1955, American Louise Arner Boyd became

the first woman to reach the North Pole by air. Boyd, a woman who had

explored the Arctic on foot for many years, chartered a DC-4 aircraft at

age 67 and had a Norwegian crew fly her over the Pole.

From the 1960s to the

present day, aircraft and pilots have largely helped transport and support

land-based expeditions across the Arctic region as well as played a key

role in search and rescue missions. However, there have been a few

significant polar flights in the second half of the 20th century. On

November 14-17, 1965, the Rockwell Polar Flight took place under the

sponsorship of Rockwell-Standard Corporation. This flight was the first

round-the-world flight to pass over both the North and South Poles,

basically going "over the top" and "under the bottom." The flight

established eight world speed records for jet transport aircraft and also

conducted scientific studies that focused on cosmic ray absorption and

high-altitude meteorology. In addition, as recently as the year 2000, two

other Arctic aerial "firsts" took place. That year, British adventurer

David Hempleman-Adams finally realized the dream of 19th century Solomon

Andree when he flew to the North Pole in a hot-air balloon. And on April

17, 2000, American aviator Gus McLeod became the first person to reach the

North Pole in an open-cockpit plane. Perhaps these two flights will help

renew interest in Arctic aerial exploration, one of aviation history's

most fascinating chapters.

|