Neither the

London—Australia flight of the Smith brothers in 1919 nor

the London—Cape Town flight of Van Ryneveld and Brand in

1920 convinced governments or airlines that routine air

transportation between these points was feasible. Cobham’s

flights accomplished this, and serious international flights

over long distance (in many countries, not just from

England) began after Cobham’s flights.

The flight to

Australia had been anything but routine. While flying over

Iraq, a sandstorm forced Cobham to fly low. Bedouins,

probably seeing their first airplane, shot at it and hit

Arthur Elliott, Cobham’s co-pilot and long-time friend.

Cobham made an emergency landing in Basra and Elliott was

taken to a hospital, but he died the next day. This incident

underscored the dangers of flying over unknown territory;

that Cobham’s flight was able to convince people that flying

was practical in spite of Elliott’s death was a tribute to

Cobham’s planning and perseverance.

Cobham is shown here returning to London

from one

such historical flight, to Australia and back.

Another of his flights was to Cape

Town, South Africa.

Cobham’s next project was

to survey the coast of Africa from the air (filming from an

open cockpit) in preparation for commercial flights to

African, Asian, and South American destinations. He then

toured England, sponsoring National Aviation Day exhibitions

that entertained and informed the public on the benefits of

air transportation. Cobham became a proponent of in-flight

refuelling, founding a company that became the world leader

in the development of that technology. He died in 1973 at

the age of seventy-nine, after a distinguished career in

aviation.

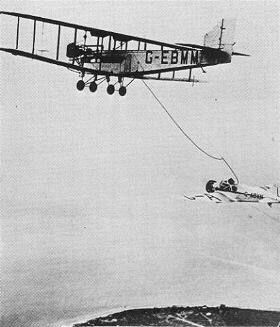

Refuelling Alan Cobham's Airspeed Courier G-ABXN from

Handley Page W10, 1934

From the close of the war

right through Cobham’s flight, one man was determined to fly

solo from England to Australia, but no one seemed of a mind

to let him. He was a short Australian named Bert Hinkler and

he had served in the Royal Naval Air Service during the war.

When flying to Australia became an

official challenge sponsored by the

Australian government and

supervised by the Royal Aero Club,

Hinkler proposed to make the flight solo in a

Sopwith Dove biplane he

convinced the Sopwith Company to

lend him. The Aero Club sanctioned

some attempts—

and eventually the Smiths claimed the

prize amid fierce competition—but two

fliers were not accepted as

entrants: Bert Hinkler, because

the Club did not believe it

possible to make the long

flight solo; and Charles Kingsford-

Smith, because he proposed to reach

Australia by crossing the

Pacific, and the Aero Club did not

believe that possible either.

Sopwith withdrew the plane when

Hinkler did not qualify, so the

Australian flier spent the next

few years test flying Avro planes

and eventually saved up enough to buy an Avro

Baby, a small plane with a

35-horse- power engine. He

attempted his solo flight to

Australia in May 1920, but had to

abandon his plan in Italy because

hostilities in the Middle East

made that part of the world

impassable.

Four years later, Hinkler now

considered an accomplished aerobatic

flier and racer, bought an

Avro Avian, a slightly larger

plane (still less than half a ton

un-fuelled) that could be outfitted

with extra fuel tanks. Knowing his

solo run to Australia would not be

sanctioned (or even permitted),

Hinkler took off from Croydon, England, on the

morning of February 7, 1928, virtually in secret.

His wife, an Avro

executive, and two passers-by were the

only witnesses. Hinkler

made the London-to-Rome flight in

record time—thirteen hours—but was

arrested when he mistakenly landed

at a military air field. Bailed out by the

British Consul, he continued the next morning,

stopping in Malta, Libya,

India, Burma, and Singapore, and establishing speed records

between London and all those destinations

along the way. (It was a great feat of flying

stamina and navigation, but

Hinkler would always claim,

ingenuously, that his most important piece of

equipment was his alarm

clock.)

By the time he reached Southeast

Asia, news had spread of Hinkler’s flight and a huge

throng was waiting in

Darwin to greet him. He reached

Australia in fifteen days, nearly halving the time it

had taken the Smiths (along

essentially the same route). He

was paraded through the streets of

Darwin and Brisbane, and awarded

medals and cash by the Australian government. The flight had

proved to be more than a stunt. It

showed that a carefully laid-out plan and solid technical

flying could put the Australian continent within two

to three weeks from England, a

short jaunt in that era.

arrival in Australia

Hinkler, by nature a shy man, became an international

celebrity, inspiring fashions,

dishes, and even dance steps.

He hit the headlines again in 1931 when he flew a

de Havilland Puss Moth in

the first solo flight across the

South Atlantic and the first east-west crossing from

Brazil to Senegal, West Africa. Again, he kept his

intentions secret (and again he was detained

by authorities, this time

the Brazilians, who found his papers not in

order). Hinkler died in

January 1933 in Italy while

attempting to set a new England—Australia speed record.