|

Flight of the

NC-4

World War I put many aviation plans on hold, which was

probably just as well. Had it not been

for the war many

more fliers would have tried crossing the Atlantic

and would have been claimed

by its icy waters. The planes of

1913 were not capable of the nearly nineteen-hundred-

mile (3,057km) flight

between Newfoundland and Ireland,

the shortest route across the Atlantic, nor of

the twenty to thirty hours

of reliable continuous operation

that would be required by any engine

that would power such a

plane.

In England, Alfred, Lord Northcliffe, publisher of the

London Daily Mail, had

offered a prize in 1913 of fifty

thousand dollars to the first aviator to cross the

Atlantic. Northcliffe had offered

other prizes—it was in pursuit of

Northcliffe prizes that Blériot had crossed

the English Channel

and Paulhan had flown from London

to Manchester—but this was

considered the ultimate prize,

and almost as soon as it

was announced, various groups in

different countries prepared to try for it.

Northcliffe realized how

difficult this feat would be in 1913. In the original rules,

the plane making the Atlantic crossing was allowed to land

on the water along the way, could be refueled in the Azores,

and even towed for repairs, as long as the flight continued

from the point of touch down. The only plane with any real

chance of making the flight would have to be a seaplane, and

at that time the best seaplanes were being manufactured by

Glenn Curtiss.

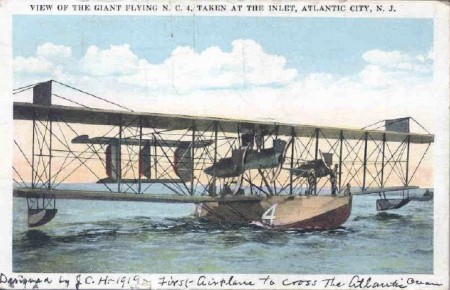

Curtiss was triumphant again in December

1918, when the U.S.

Navy unveiled the NC seaplane. With a wingspan of 125 feet

(38.lm),

it was among the most formidable

planes then in the air

While in England looking for buyers of

his planes, Curtiss met British naval commander John Cyril

Porte, who apprised him of the Northcliffe challenge and

even found him a financial backer in Rodman Wanamaker, the

Philadelphia merchant millionaire. (Porte, who was stricken

with tuberculosis and didn’t expect to live very long, even

offered to fly the plane across the Atlantic!) Curtiss began

testing his seaboat designs back on Keuka Lake and by

February 1914 had a gangly-looking aircraft that he

calculated would be able (just) to make the crossing.

The

aircraft was one of the largest built to that time, with a

forty-five-foot (13.5m) podlike hull, 126-foot (38.5m)

bi-wings, and three large engines, the entire aircraft

weighed more than twenty-eight thousand pounds (12,712kg).

Curtiss built two models and prepared to fly one, dubbed

America, to Newfoundland for the trans-Atlantic launching,

which after many delays was set for August 15, 1914.

The outbreak of war on August 4 made the

flight of the America impossible, but the British Admiralty

was so impressed with the performance of the planes that it

ordered sixty of them for submarine patrol. By the end of

the war, several things had changed. Curtiss was now

building planes in partnership with the U.S. Navy—the planes

were thus designated NC for “Navy- Curtiss” and

soon came to be called “Nancies”— in a larger plant in

Buffalo, New York.

The planes were now outfitted with four

powerful Liberty engines, the only advance made in American

aviation during the war. And Curtiss and navy engineers,

under the supervision of G.C. Westervelt, designed a

stronger, lighter, more streamlined hull.

The forward lookout of the NC-4

in flight (shown here in

1918) provides a sense of the aircraft’s scale.

RIGHT: The crew of the historic Atlantic

crossing (from left): Lieutenant Commander A.C.

Read; pilot Lieutenant E.F. Stone; pilot

Lieutenant W Hinton; radio operator N.C. Rodd;

engineer E.H. Howard; and reserve pilot

Lieutenant J.L. Breeze, Jr.

The navy decided (with strenuous lobbying by

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt) to

attempt the trans-Atlantic flight anyway “for scientific

purposes". A squadron of three Nancies took off from

Rockaway, New York, for the first leg of the trip to

Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland, on May 8, 1919. The lead craft,

NC-3, was piloted by a crew of six commanded by John H.

Towers, a famous Curtiss-trained Navy flier who had been

scheduled to fly the America in 1913.

The NC-1 was commanded by Patrick N.L.

Bellinger, also a famous flier, and the NC-4 was commanded

by Albert C. “Putty” Read. (The NC-2 had been used for spare

parts for the other three ships.) Read, a quiet New

Englander who earned his nickname because his face rarely

showed any emotion, was, at five-foot-four, the most

unlikely looking hero of the group and was not expected to

finish. In fact, the NC-4 went down eighty miles (128.5km)

off the Massachusetts coast with a broken connecting rod and

had to taxi through the night to the naval station at

Chatham.

It took six days for the repairs to be

completed and for Read to resume the flight, but he still

managed to catch up to Towers and Bellinger, who had been

fogged in, and the three planes took off on May 16 in V

formation. The route was marked by a string

of twenty-five navy

destroyers spaced fifty miles

(80.5km) apart. Problems plagued

the NC-1 and the NC-3 almost

from the start and, at one point, with

both their radios unable to transmit

and the fog making

navigation all but impossible,

both Towers and Bellinger decided

to put down to get their bearing

and attempt repairs.

Both aircraft were badly damaged in

landing and for them the flight was

over. The crew of the NC-1

was picked up by a Greek freighter, but Towers

and the NC-3 were not

spotted and the plane drifted for

nearly three days. Fighting sixty-mile-per-hour (96.5 kph)

gales and rough seas, hoping that as they were

floating backward they were being

blown toward the Azores, and

requiring a crew member to climb out to the end of a

wing and hang on for most

of the sixty-hour ordeal in order

to balance the craft after a portion of the wing on

the other side broke off,

the NC-3 finally limped into Horta

Harbour in the Azores. (Ironically, the element of

the entire mission that

drew the most notice from aviators was Towers’ seamanship

and not Read’s airmanship.

The NC-4 taxis into Lisbon Harbour, having

completed the first crossing

of the Atlantic by air—on May 27,

1919, eight years before

Lindbergh’s

historic flight. Some experts were

reluctant to acknowledge the

achievement because the seaplane covered

some of the

ocean miles on water, but most

hailed the crew as heroes of flight.

Far more powerful land-planes were already in existence

and in just a few weeks,

one would complete a non-stop

crossing of the Atlantic. But Towers had shown that the

sea could be counted on as

a safety buffer for a plane that

went down over the ocean. It led to the

rise of the great flying

boats as the primary intercontinental transport aircraft of

the 1930s.)

Meanwhile, Read and his crew flew the NC-4 to the

Azores, arriving on May 17. They waited

there anxiously for the

NC-3 as they repaired the NC-4 and prepared for

the next leg of the trip to

Lisbon, Portugal.

Read knew that word of his success

would reach two crews back in

Newfoundland who would race to launch their aircraft

and still beat him to England—although not

by air— (demonstrating that

the Daily Mail money was not all

that important to the aviators.) One was the

Sopwith team, flying a

biplane called Atlantic, and piloted by

Harry Hawker and Kenneth

Mackenzie Grieve; the other, the

Martinside team of Frederick P. Raynham and

William Morgan, flying a

biplane called the Raymor (a

combination of the aviators’ names).

The Atlantic took off first

on May 18 and the Raymor followed

two hours later.

The Raymor never made it aloft; a

gust tipped the overloaded

aircraft on takeoff, crushing a

wheel, and the plane dug nose-first into a

bog, a total loss. The

Atlantic did little better: the radiator

clogged and the engine started

overheating over the mid-

Atlantic. An hour into the flight, Hawker knew he wasn’t

going to make it. In a bit

of inspired airmanship, Hawker

headed south toward the shipping lanes, hoping to spot

a freighter he could ditch

near, while he bobbed up and down

trying to air-cool the engine. He

spotted a ship that turned out to

be a Danish freighter with no radio and he

put the Atlantic down.

Hawker and Grieve were rescued

(and, amazingly, so was the floating Atlantic a few days

later), but there was no

way of getting word to England

until the ship reached British waters on May 25.

Hawker and Grieve arrived in

London just as the memorial ceremony honouring their

martyrdom was concluding.

With both challengers out of the running, Read took

his time and set out for

Lisbon on May 25. He landed on May

27, completing the first crossing of the Atlantic by

an airplane. Two days

later, Read took off again (Towers

refused to relieve Read of command of the

NC-4, even though navy

protocol would have allowed him to do so)

and landed in Plymouth,

England, on May 31. The success of Read and the NC-4 was

hailed by the British and the

French no less than by the Americans. All three countries,

in fact, heaped medals and

accolades on the crew of the NC-4.

What puzzled Read, though, was that he

arrived in England in the

middle of a similar celebration of

the accomplishment of Hawker and Grieve. (Read had

to ask several times to

make sure he got it right, that the

pair had failed to cross the Atlantic by air.

What made matters even more

confusing was that the Daily Mail

awarded the pair a twenty-five-

thousand-dollar consolation prize; Read and his crew were

offered nothing.) The flight of

the NC-4 was quickly forgotten: a

non-stop flight across the Atlantic was only a few weeks

away and the

great flights of the next decade eclipsed the

accomplishment of Read and his crew. Even at the

time, few newspapers

covered the flight (admittedly difficult

for reporters to keep up with), and the

most extensive reporting on

the operation was filed by a Yale undergraduate for the Yale

Graphic.

The reporter was named Juan

Terry Trippe, and he would later become the creator

of Pan American Airways and

pioneer the great flights of the

clipper flying boats to South America.

For many years, the NC-4

was stored in a forgotten hangar and

gathered dust; it was even

broken up into several pieces and

stored in a number of places. Read died in relative

obscurity in 1967 near

Washington, D.C., but he lived

long enough to see the NC-4 restored after World War

11 and to see his contribution to aviation history

remembered and acknowledged.

|